Table of Contents

In the 1940’s, we visited hydraulic and dredge mining operations in Alaska and California. He also reviewed 10 yr of accident data pertinent to such mining in the United States. The data, covering the period 1933 to 1942, included those related to 36 fatalities and 3,700 injuries in dredge mining.

It is generally assumed that dredge operations are “safe”—certainly much safer than other mining and construction operations to which they are usually compared. It is true that personal injury rates for dredge workers, normalized in terms of worker-hours, dredge operating hours, or tons of material moved, are lower than those for many other mining operations. Still, over the 10½-yr period that ended in June 1983 63 people were killed and almost a thousand injured in mining dredge operations in the United States.

The research discussed here included field visits to a selected sample of mining dredge operations, an examination of dredge-related injury data in the files of the Mine Safety and Health Administration’s Health and Safety Analysis Center in Denver, and field visits to a selected number of nonmining dredge operations. In all, field visits were made to 31 dredge operations. Three companies whose principal business is the manufacture of dredges and dredge components were also visited. Design considerations for safety were discussed, as were training and product liability questions and the accident experience of company field representatives during erection, initial operations, and maintenance of delivered dredges.

The information was analyzed in five separate categories which appear to be the most important in terms of developing countermeasures for these accidents. These categories include drowning, slips and falls, electricals mechanical, and fire.

Dredge Accidents

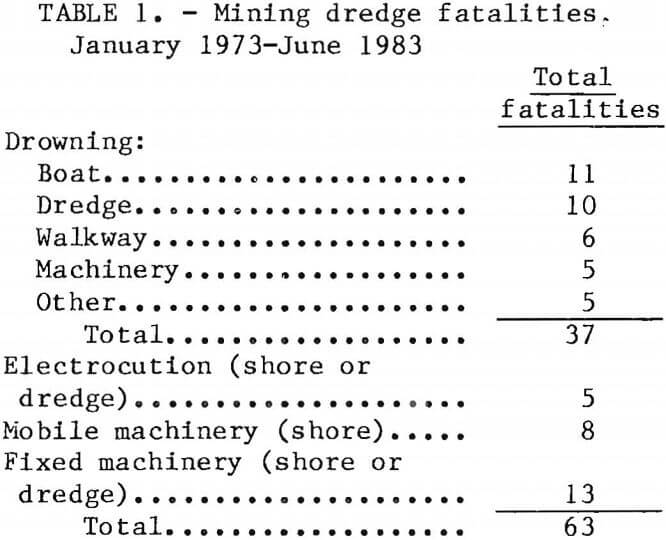

To try to quantify the hazards, data were taken from the Mine Safety and Health Administration’s accident records since January 1973. Table 1 shows the fatal accidents that occurred on U.S. mining dredges during those years. Six people (average) died each year. There was also an annual average of more than 95 nonfatal injury accidents, as well as several hundred noninjury accidents. Note that about 59 pct of the fatalities in the table are drowning accidents. There were more drownings from boats and walkways (mostly pipeline walkways) than from the dredges themselves. Machinery accounted for a smaller number. An example of such an accident is one in which a worker was repairing a dredge-to-shore conveyor belt. The belt was started while he was working on it, and he was knocked into the water. Five of the fatal accidents were from electrocutions. Twenty-one fatalities involved shore- or dredge-based support equipment, including a rollover of a front-end loader, a falling crane boom, a fall into a hopper, and conveyor accidents on land.

Dredge Operations

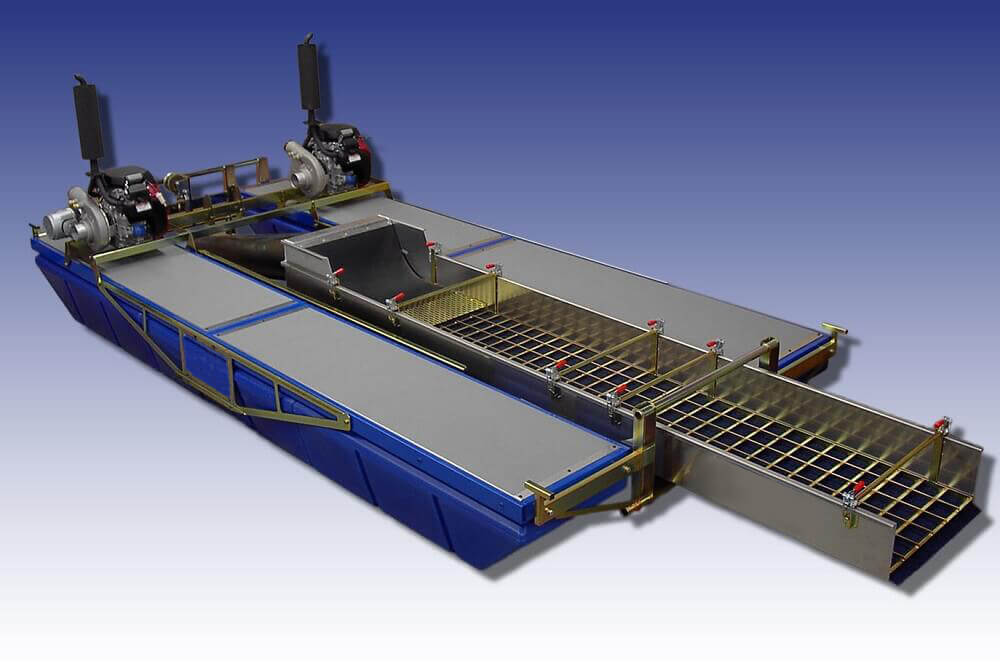

The majority of the dredges visited were extracting sand or gravel. Others in the sample included units engaged in recovering phosphate, gold, ilmenite, and coal. Dredges involved in land reclamation after mining and settling pond maintenance—for example, in recreational area development, specifically units engaged in making lakes for fishing and water sports—were also included in the analysis.

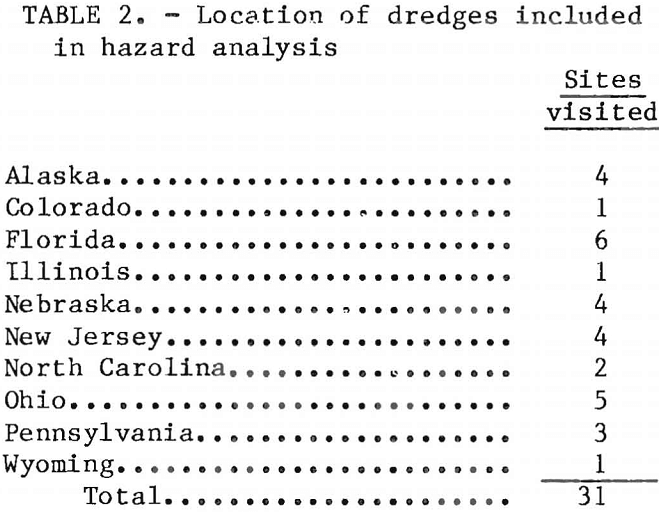

Of the 31 dredges visited, 18 were built by manufacturing firms whose principal business is the design and manufacture of dredges. Thirteen units were built by the owners or by local machine shops not primarily engaged in dredge design and construction. The 31 dredge operations included in this analysis were located in 10 States (table 2). Three of the four Alaskan dredges were mining gold.

General Hazards Analysis

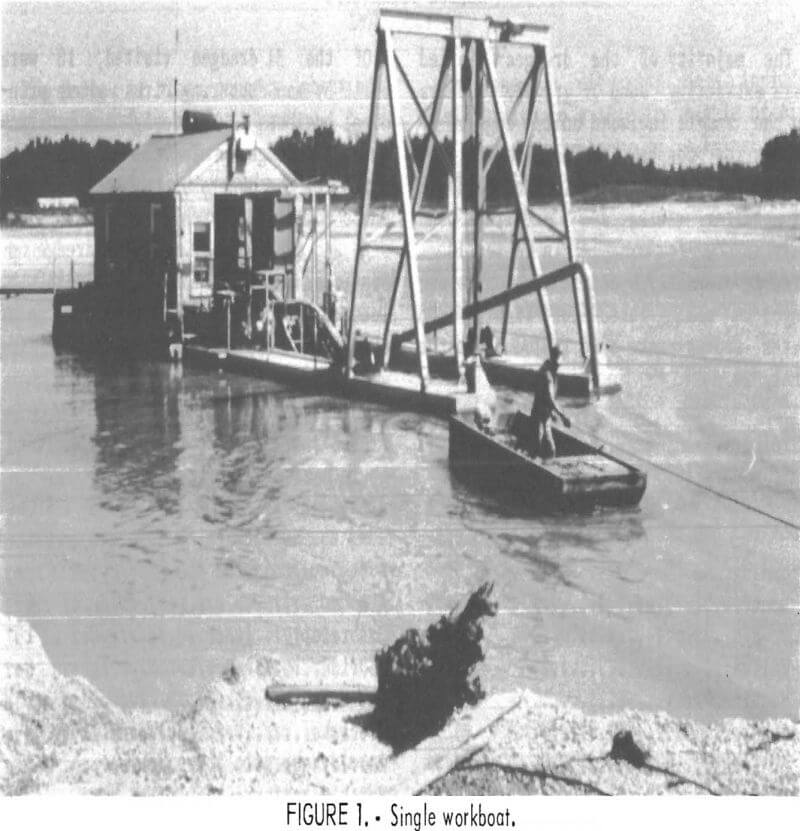

Many dredges depend upon a workboat to transport personnel and materials between the dredge and shore (fig. 1). It is important to note that most of the dredge operations that depend upon a boat had only one such boat. Several fatal accidents might have been avoided had a second boat been immediately available to enable persons who might have rendered aid to get to the dredge quickly. In these accidents the only available boat was tied up at the dredge, and the victim was the only person on the dredge.

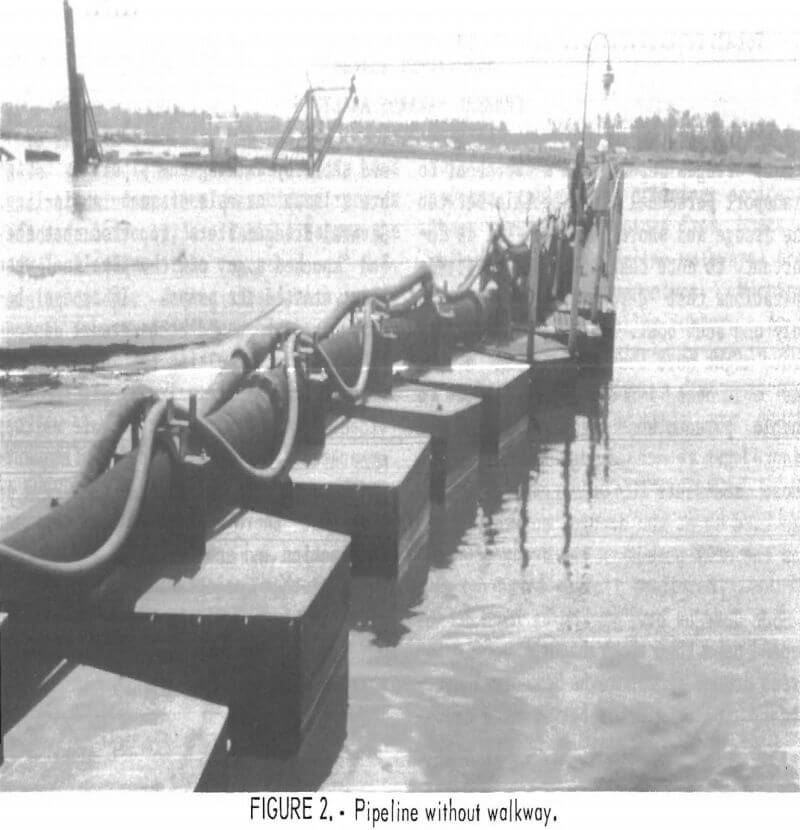

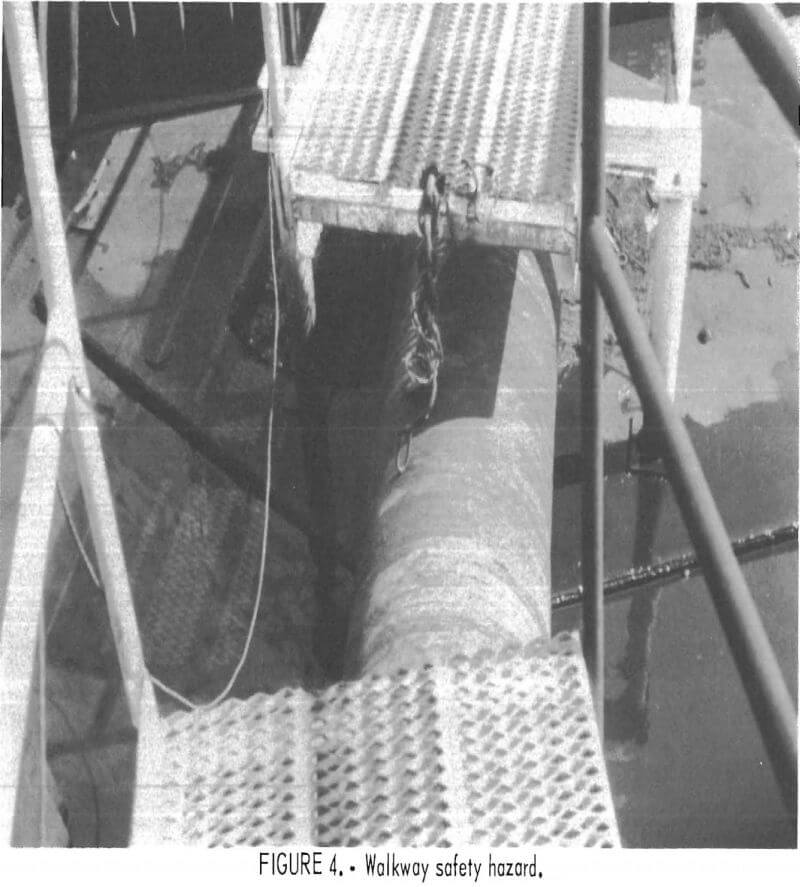

Some dredges have workboats but do not depend upon them to transport people be-tween dredge and shore as a normal practice. The crew moves between the dredge and shore by walking the pipeline Figure 2 is an example of such a pipeline. Several dredgemasters reported that they had “knocked a guy off the pipeline” when they started the pumps. If access between the shore and the dredge depends primarily upon walking the pipeline, it follows that a safe walkway must be provided. Figure 3 shows a safe walkway separated from the pipeline. Infrequently, however, the design of the walkway is such that there are large gaps between one section and another (fig. 4). In adverse weather negotiating a gap of this size can be particularly difficult and hazardous undertaking for the dredge worker.

Pipeline Hazards

A more specific hazard associated with pipelines is related to moving the line and making repairs where the job of making connections between sections involves the danger of crushing or pinching injuries. Although several dredges provided work platforms on the pipeline buoyancy structures, many do all the work from workboats, sometimes using people who have little skill in boat operation or safe mooring.

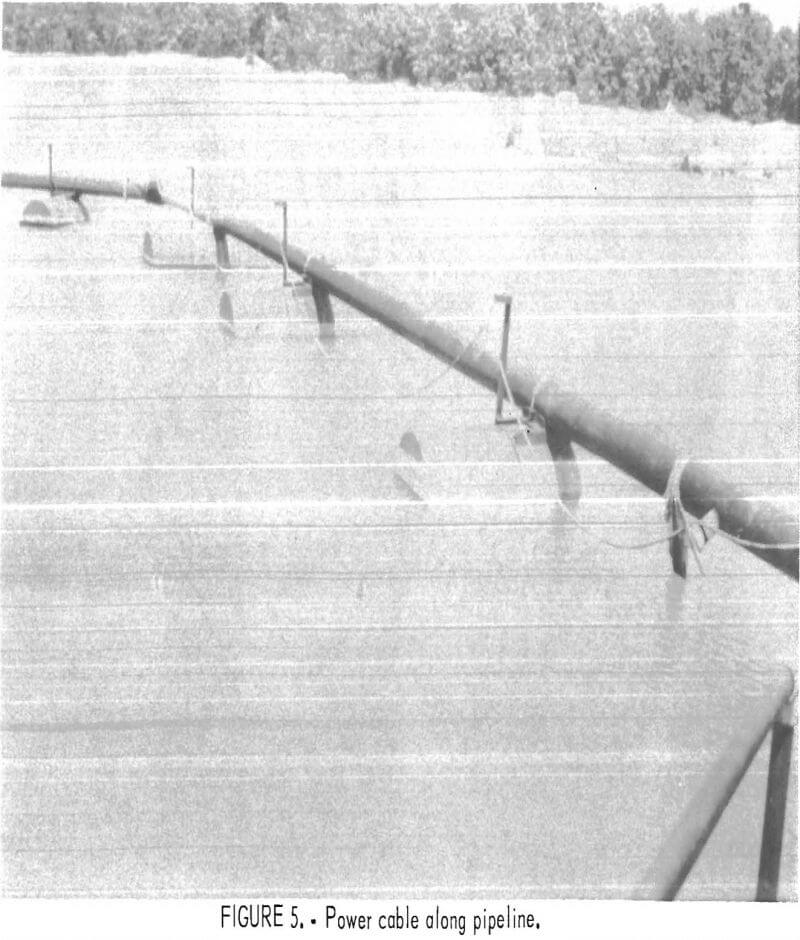

Another hazard area related to the pipeline involves power cables carried along the pipeline. One obviously unsatisfactory arrangement is shown in figure 5. If the insulators that carry the line are inadequate, or if the line droops into the water, chances of breaking or electrical shorts are greatly increased.

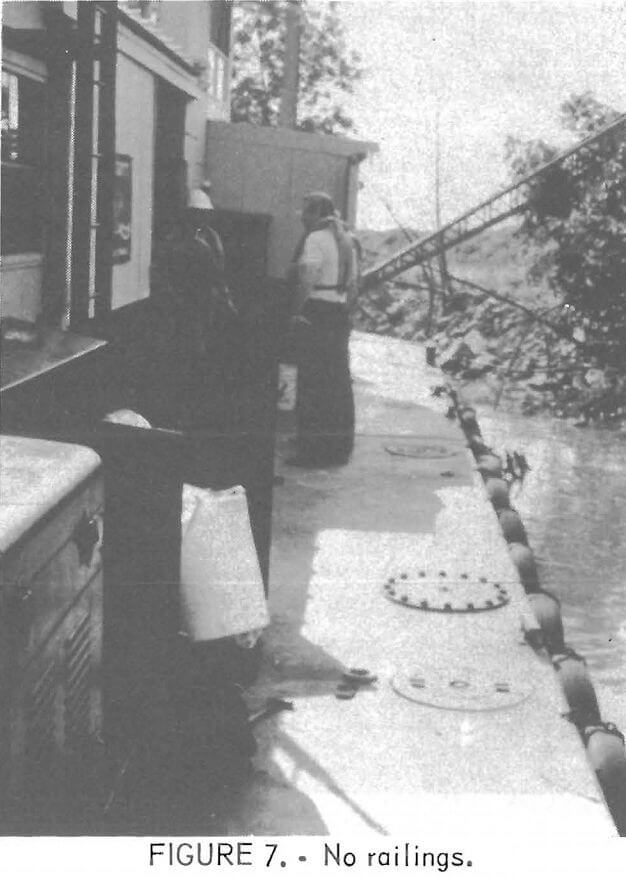

Railing Hazards

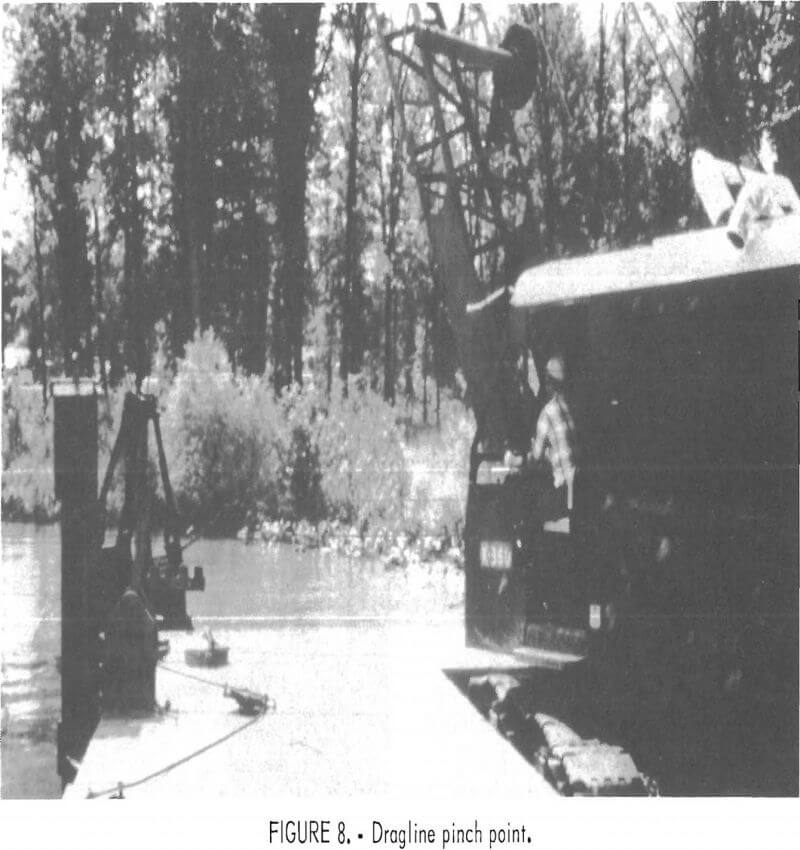

As on the pipeline walkways, railings make an important safety contribution on dredge decks. Many dredges had strong, well-maintained deck railings (fig. 6). Some, however, had no railings at all (fig. 7). A need for guardrails inboard was evident on the type of dredge that mounts a dragline in a deck well. Two of the dredges visited had arrangements similar to that show in figure 8. Note that as the dragline swings, a pinch point is created between the cab and the deck. Several accidents have occurred when maintenance people were not aware of this

potential hazard. The problem is not one of having maintenance, done during drag-line operations, because most companies require that the dragline be stopped during maintenance. The accidents that have occurred involved people doing deck-work and inadvertently stepping into the well.

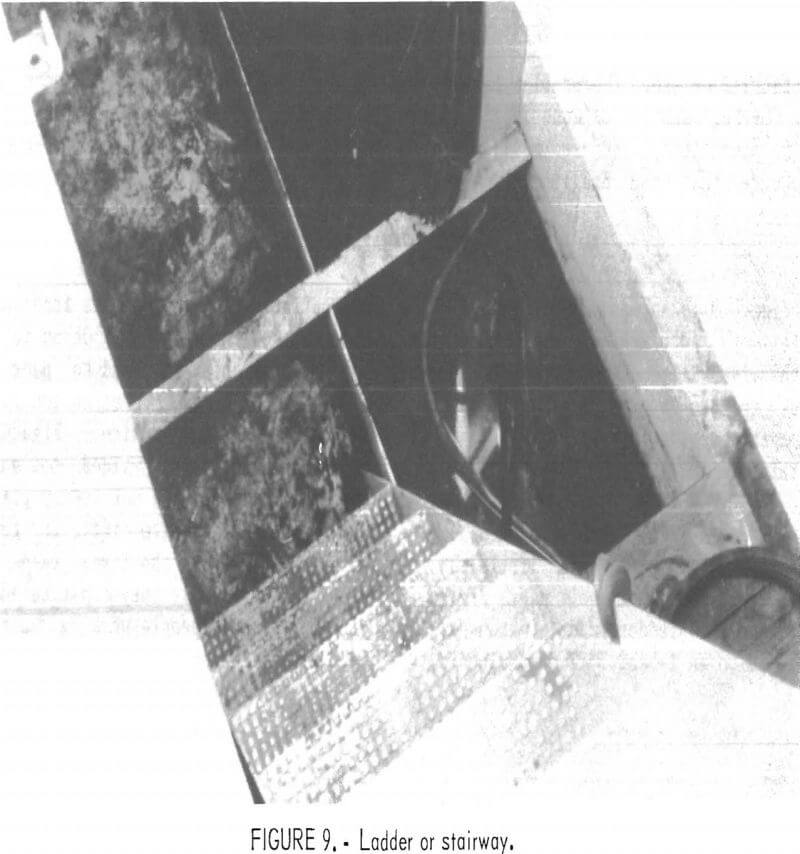

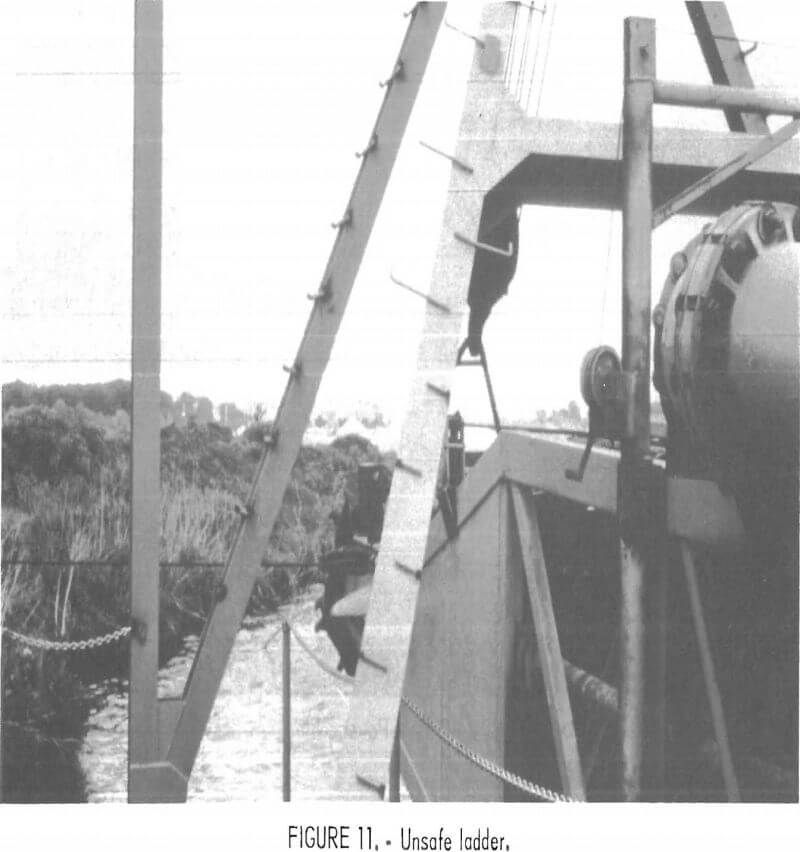

Ladder Hazards

Figure 9 is an example of a ladder (or stairway) into a lower hull area of an otherwise well-constructed dredge. Note the absence of handrails. Tripping and bumping hazards are also visible in the stairwell area.

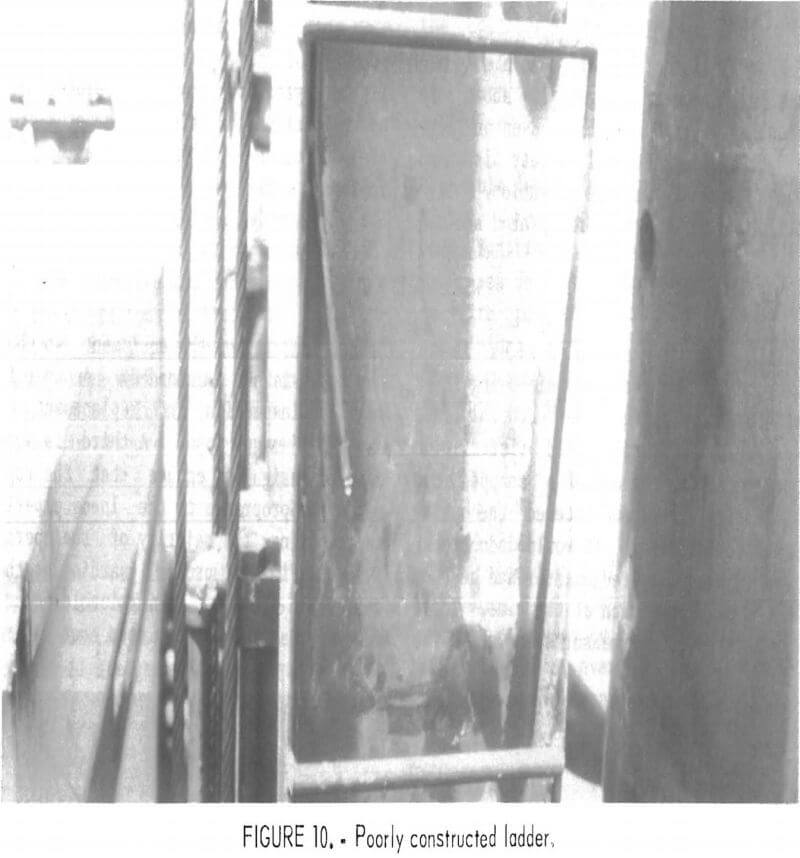

Ladders for above deck maintenance are frequently designed with little thought about the safety of their use. Figure 10 shows such a ladder, made of round stock welded to an I-beam. The spacing is inappropriate, the the room is inadequate, and the footing is poor. Often it was not a cost problem that led to poor ladders, but simply lack of attention to the details of safety design. Figure 11 shows another ladder welded to an A- frame. The rungs are not evenly placed, and the ladder is quite difficult to negotiate. Some of the lower rungs have been removed because they constituted another hazard to people working near the base of the A-frame.

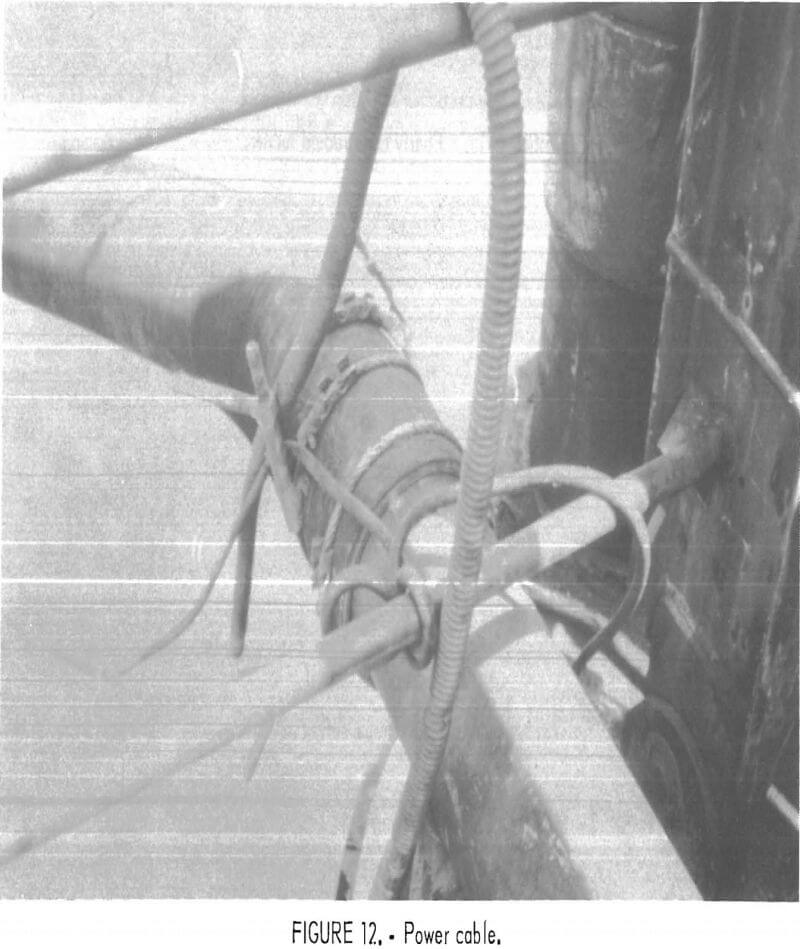

Electrical Hazards

Electrical hazards are common on many smaller dredges-. Figure 12 shows poor handling of a power cable. Even on larger dredges, electrical safety is sometimes given inadequate attention. Distribution boxes are poorly placed and improperly mounted. Cables are routed with little regard for insulation protection, not to mention the trippling hazards created. Common safety practice must be followed.

Wire Rope Hazards

Wire rope breakage on dredges is not uncommon. Both broken positioning lines and broken digging ladder control lines were observed during field visits. On one occasion, the end of a snapped rope violently struck and entered the operator’s compartment. It would undoubtedly have injured the dredgemaster had he been in his usual position at the time. There are several countermeasures. One is the proper handling of the equipment so that the rope is not overloaded. Another is regular inspection and replacement of work or damaged rope. A third is more careful design to ensure that the rope size is appropriate to the loads experienced during the majority of the operations. Finally, proper guarding of the cables and drums can be invaluable to ensure that a broken cable does not injure

a worker. Although some of the ropes and sheaves observed during the study were well guarded; most were not. Many drums including drums immediately adjacent to the operator’s compartment, were not guarded.

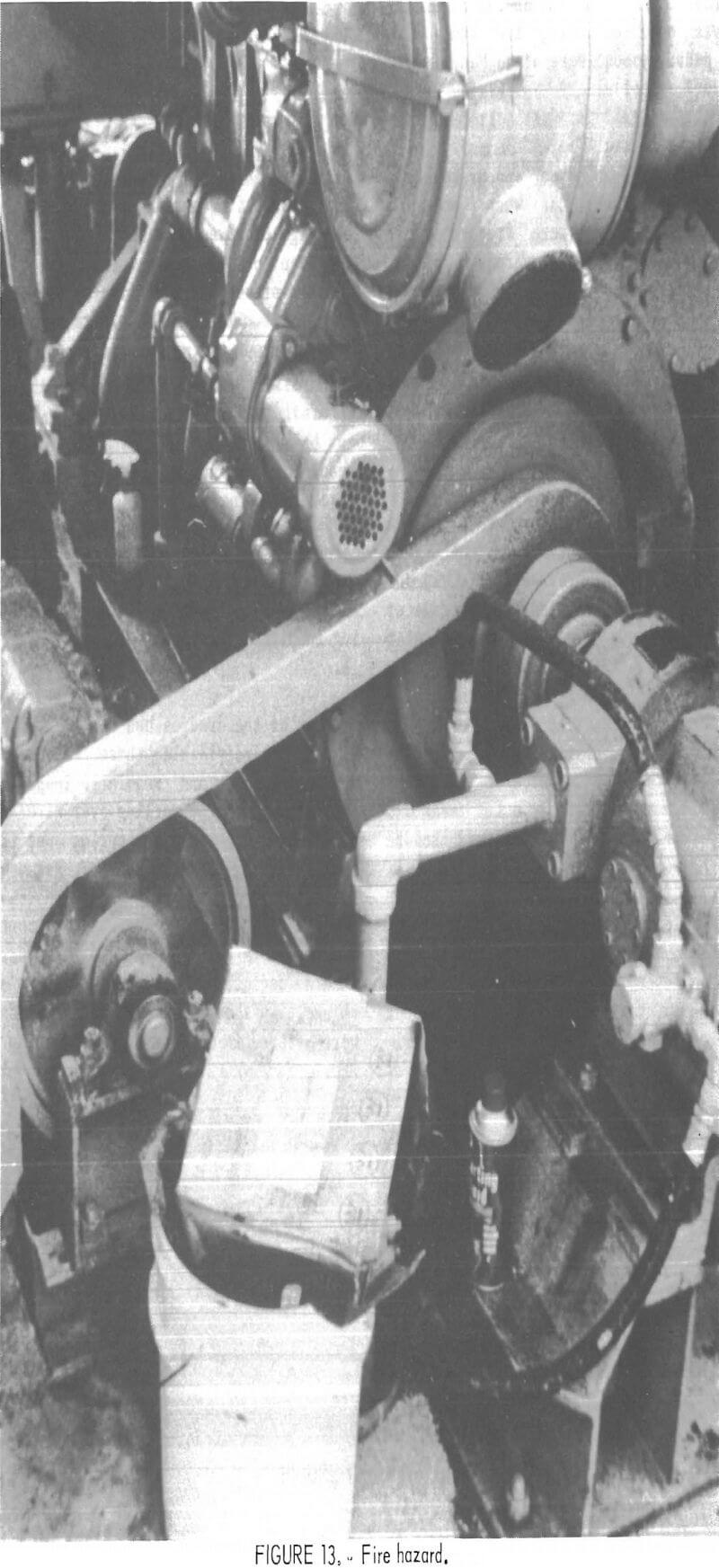

Fire Hazards

Fires on dredges do not appear to be a common occurrence, but when one did occur, the results were frequently extremely expensive and dangerous. In most of the operations visited, the fire protection practices appeared to be substantially less well developed than those in shore-based plants. Scenes like that shown in figure 13 were very common.

Flammable debris (oily rags, cartons, and fluids) were frequently observed in areas where ignition was possible. The training given to most dredge workers relative to fire prevention and fire suppression was minimal. The available fire suppression equipment was not always easily accessible and properly maintained.

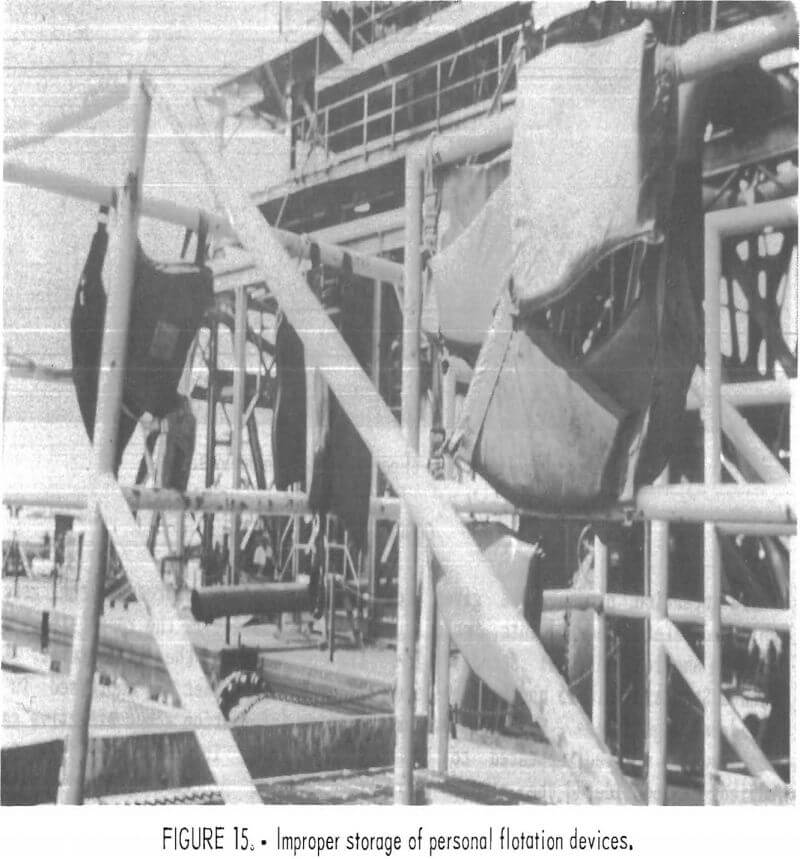

Personal Flotation Device

Perhaps the single greatest hazard on dredges is related to the simple fact that work is done over water. Only one of the 31 dredges vistied required water survival training and demonstrated water survival proficiency as conditions of employment. All except two of the dredge operations required the wearing of a personal flotation device (PFD), according to the written safety rules of each company. However, in only a few cases was the wearing of PFD’s observed to be enforced.

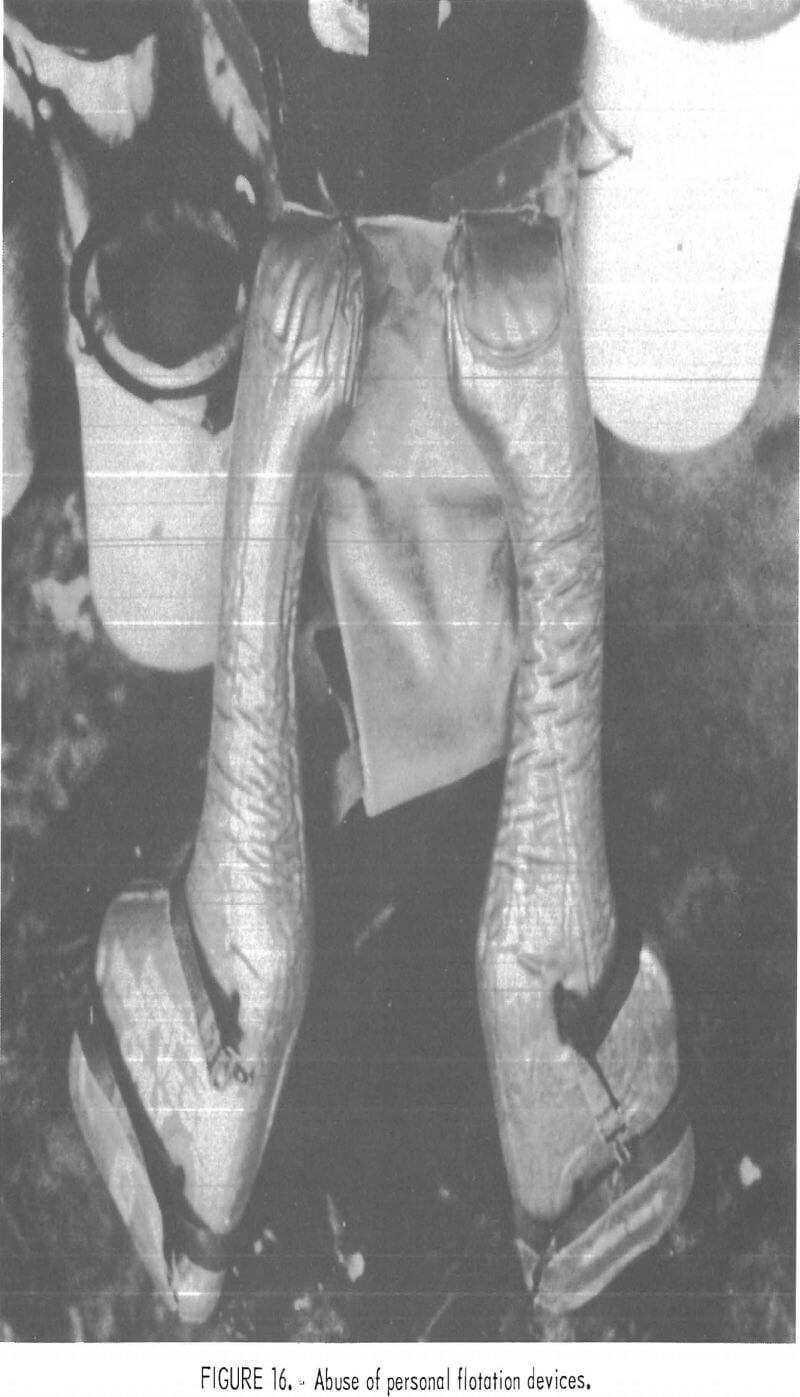

In the majority of operations visited, no one was wearing his PFD. Scenes like that depicted in figure 14 were common. On some of the very smallest and oldest dredges it was apparent that the available PFD’s were never worn. On some of the largest it was not uncommon to find PFD’s stored as in figure 15, not well-maintained, not inspected, not fitted, and not assigned to individuals. Some-times the PFD’s, even new ones, were lying in dirt and grease as shown in figure 16.

A few of the dredges had the PFD’s assigned to individuals; these PFD’s were well maintained and regularly inspected and were worn while working over water at all times except when the person was inside the dredge control house. However, at most operations the dredge workers complained that the PFD was uncomfortable, too old to be of any use, or a work hazard because it tended to catch on things. In short, a multitude of reasons were offered in defense of not wearing a PFD.

Conclusions

More attention needs to be given to published safety requirements, including those in American National Standards Institute Standard A10.15 and in the Code of Federal Regulations. The three dredge manufacturers visited appeared to have studied and considered the standards in terms of design improvements. Beyond that, all three expressed the general view that safety is the responsibility of the operator, not the manufacturer. Considerable interest was expressed in obtaining information about effective safety practices, including the development of safe job procedures, at many of the operations visited.