Table of Contents

Dredge Operation Visits

The contract requirement was that nine mining dredge operations be visited to gather data on the operations, their safety hazards, and their safety management. Although the number of field trips made was the same as originally planned, 31 dredges were visited. There were several reasons, but the most important were:

- It was desirable to sample mining dredges of several types, mining a variety of minerals, and operating in different geographic areas, for sound hazard analysis.

- Many dredge owners were very cooperative in arranging visits to their operations, making it possible to schedule several visits on a single trip.

- Discussions at one operation invariably suggested visits to others which were using different equipment and different mining plans. Visits to MSHA subdistrict offices also produced suggestions about operations which should be included in the hazards analysis.

The following subsections describe the dredge operations observed.

Location Mining Type and Construction

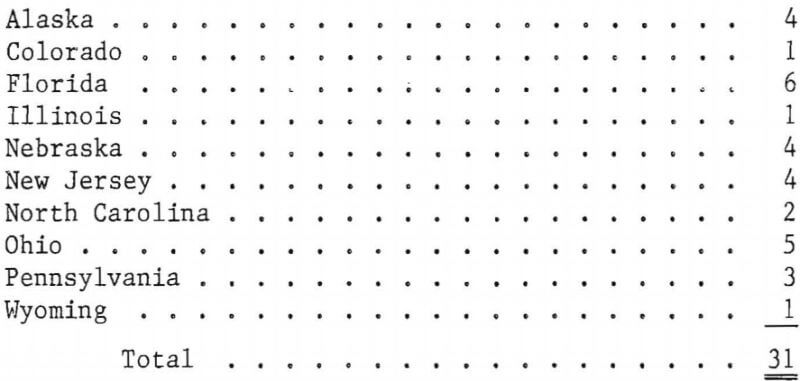

The dredge operations were in ten states as follows:

Most of the operations were engaged in mining minerals for commercial markets. Five of them were not. These five used dredges identical to those employed in some mining operations, but in construction and maintenance work. They are owned and operated by government agencies. It was desirable to compare hazards and safety practices on these dredges to hazards and practices observed at mining operations.

The dredges visited were engaged in eight categories of work:

- Sand and gravel mining

- Phosphate mining

- Gold mining

- Ilmenite mining

- Coal mining

- Mining reclamation, or settling pond maintenance and fines recovery

- Channel development and maintenance

- Recreational area development and maintenance

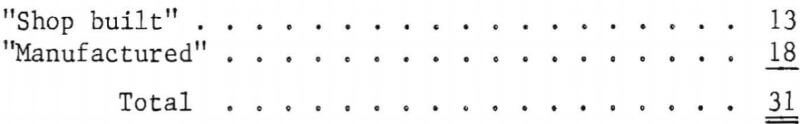

During the Phase I work, the origin of the mining dredge fleet was discussed with dredge owners, manufacturers, and consultants. It was anticipated that there might be significant differences between operation and maintenance hazards on dredges constructed by companies whose principal business is dredge manufacturing and on those designed and constructed by their owners or by local machine shops. The latter were called “shop built” dredges to distinguish them from “manufactured” dredges. The dredge visits were planned to include-a sample of both. The total was divided thus:

Manufacturers and consultants visited during Phase II gave various estimates concerning the percentage of the mining dredge fleet composed of “shop built dredges. Estimates ranged from 40% to approximately 60%. There were no data obtained in this program to verify or refute any estimate given.

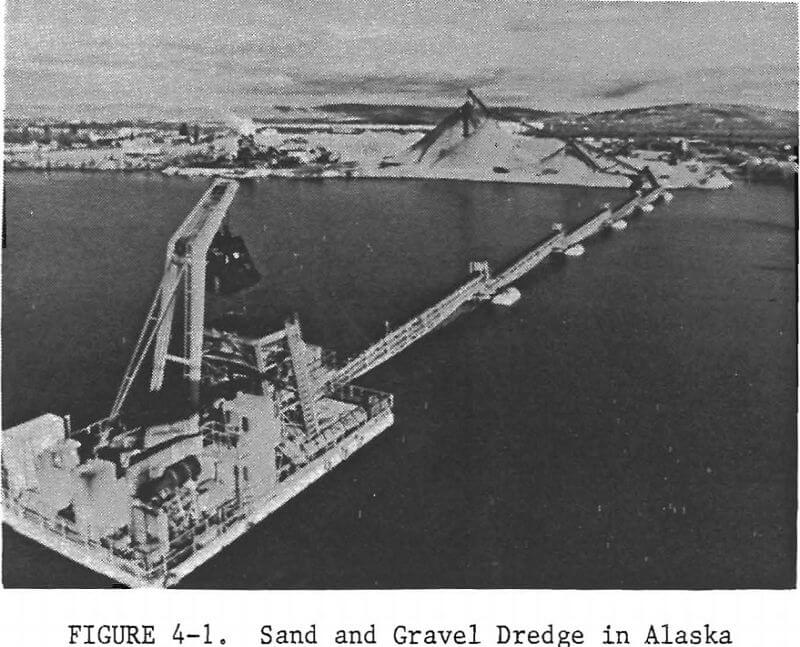

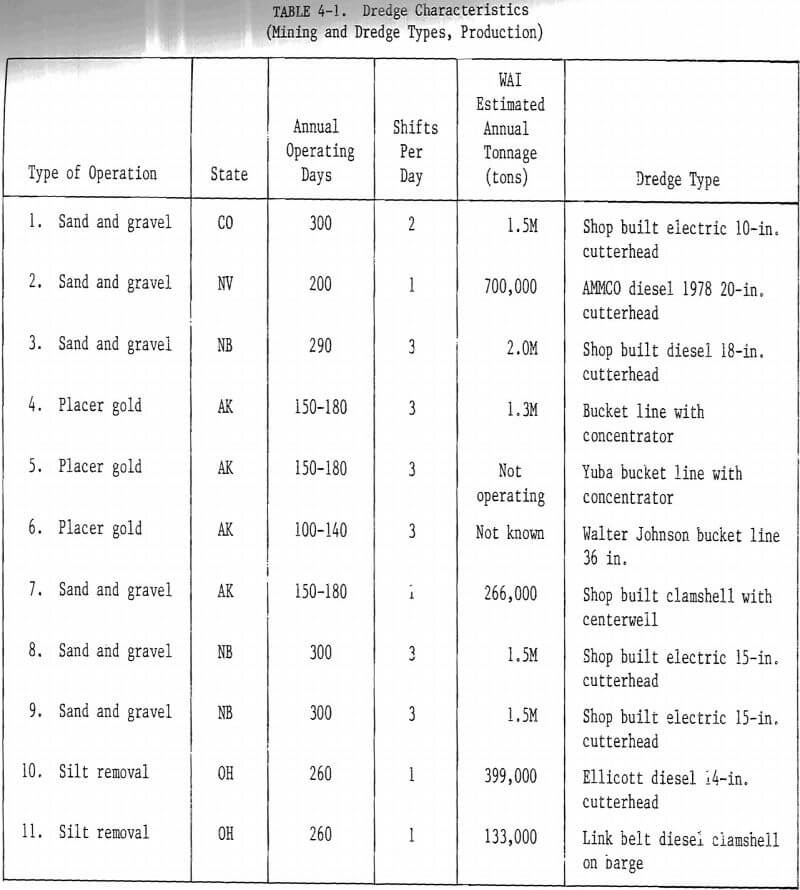

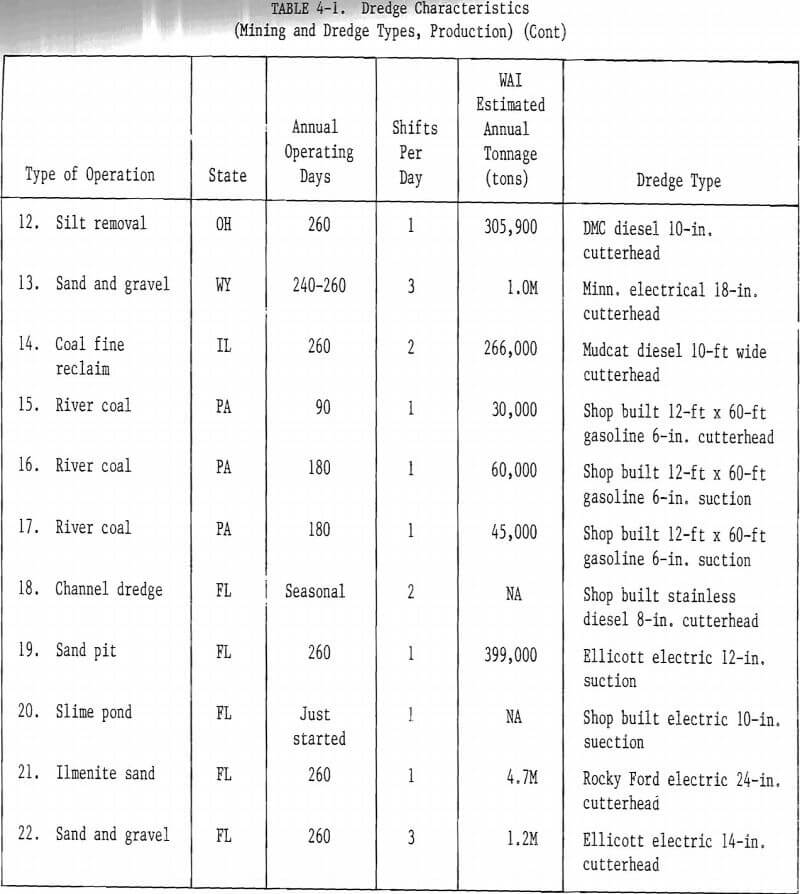

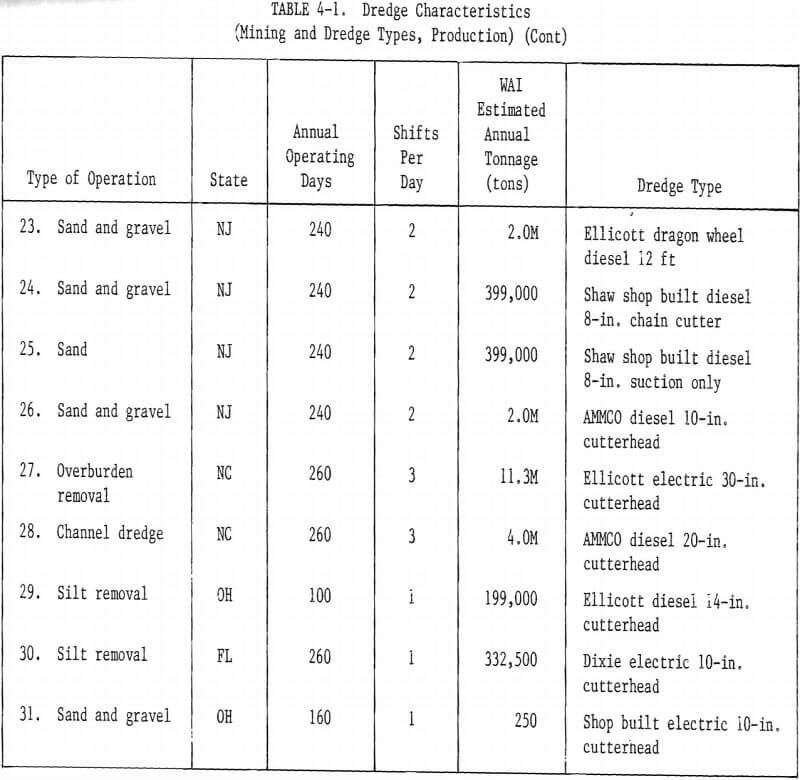

Figures 4-1 through 4-6 illustrate the variety of dredge operations visited. The estimated amount of material dredged annually at each operation ranged from 45,000 tons to more than 11,000,000 tons.

Operational Factors

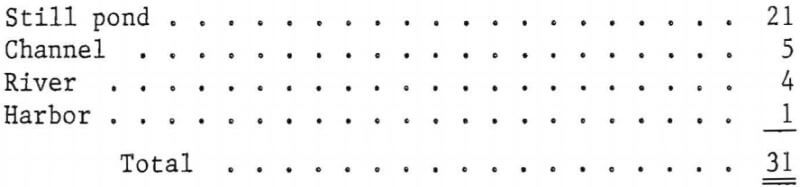

Two-thirds of the dredges observed were working in still water, primarily in ponds constructed specifically for the dredge. Some of the ponds had fixed boundaries, because of terrain or land ownership limitations, but most changed boundaries as the dredging progressed. Some of the dredges operate for several years within a given area. Others move, usually over land, to a new area after periods of operation of less than a year.

The kinds of water on which the dredges operated were:

Several of the still ponds were constructed along a river or creek bank.

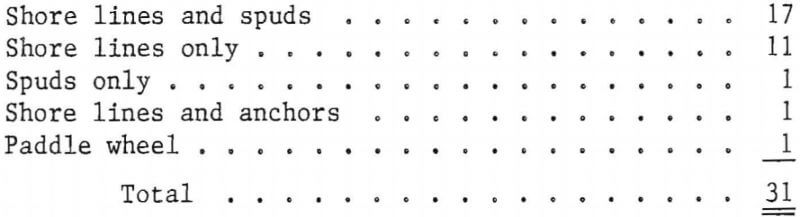

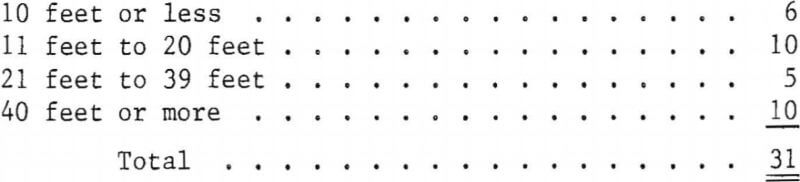

The positioning methods used by the dredges fell into five general categories:

The digging depth of the dredges ranged from 8 feet to 120 feet. The dredges operated normally in maximum digging depth groups as follows:

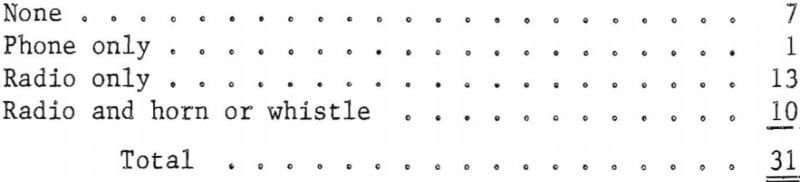

The communications from dredge to shore were:

Manpower Factors

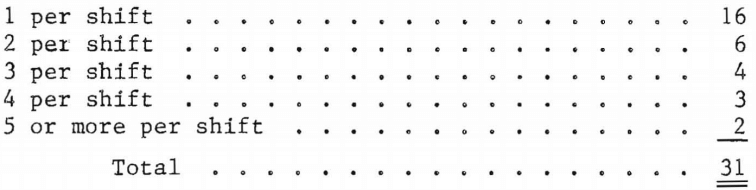

Approximately half of the dredges visited had only one person, the dredge master, on duty on the dredge itself each shift. The number of workers assigned to the dredge was:

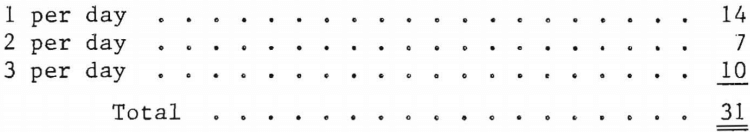

The length of shift ranged from 8 to 10 hours normally. The number of shifts per day worked on the dredges visited were:

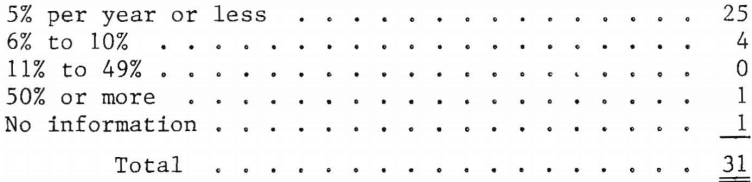

The work force on the dredges was very stable in all but a few locations. Several reported turnover as “very low.” When questioned further, the operators reported personnel losses which amounted to annual rates of 5% or less. Three of the dredges had been operating less than a year, with no personnel changes. A general summary of turnover rates is:

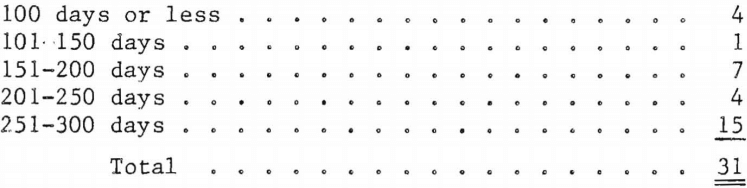

Approximately half of the dredges visited worked more than 250 days a year. Several were seasonal operations which worked 3 to 5 months each year. Some of these worked 24 hours every day of the week during the operating season. The dredges were divided among average annual working day groups thus:

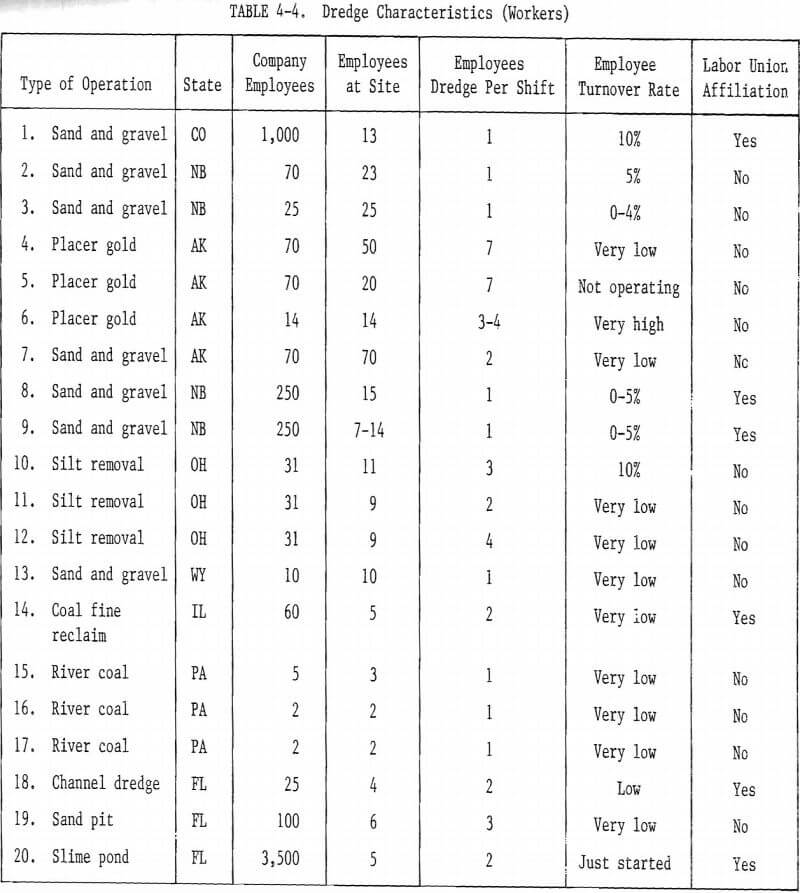

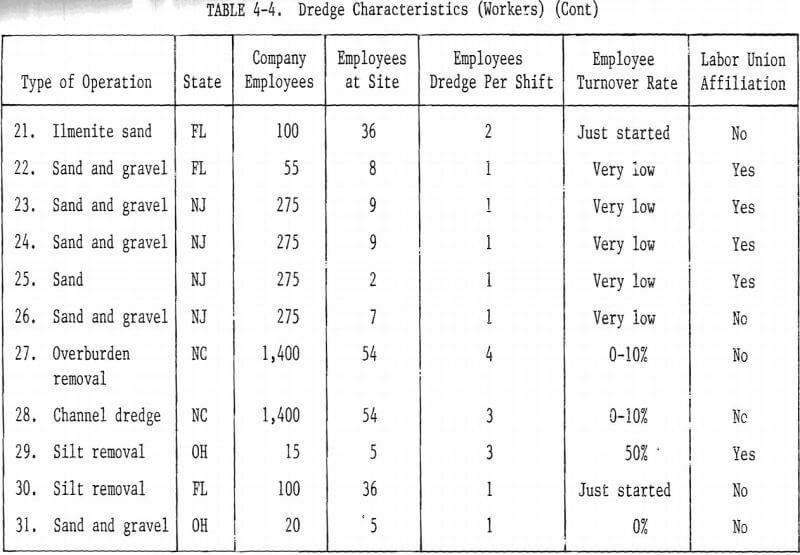

Eleven of the dredges visited were operated by companies whose, workers were represented by a labor union. The other 20 were operated by nonunion companies. Although 35% of the dredges were operated by “union companies,” only 16% (or 5) had dredge masters who were union members.

The size of the companies which operated the dredges, measured in numbers of employees, ranged from very small (2 employees) to very large (3,500). Approximately 60% (or 18) of the dredges were operated by companies, or government agencies, with less than 100 employees.

Characteristics Tables

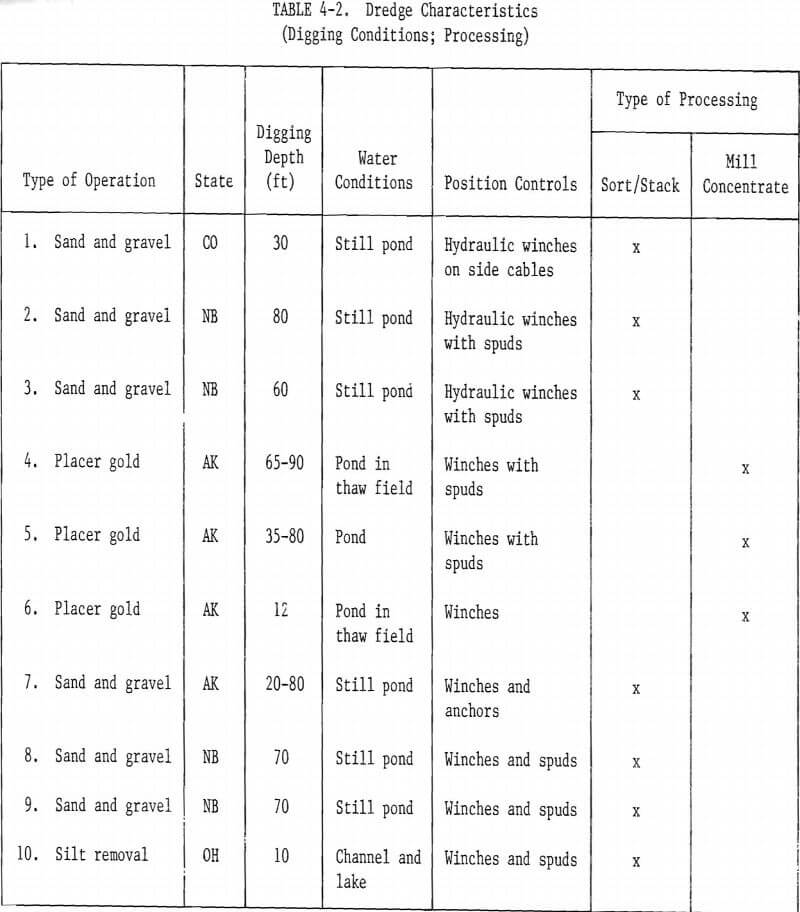

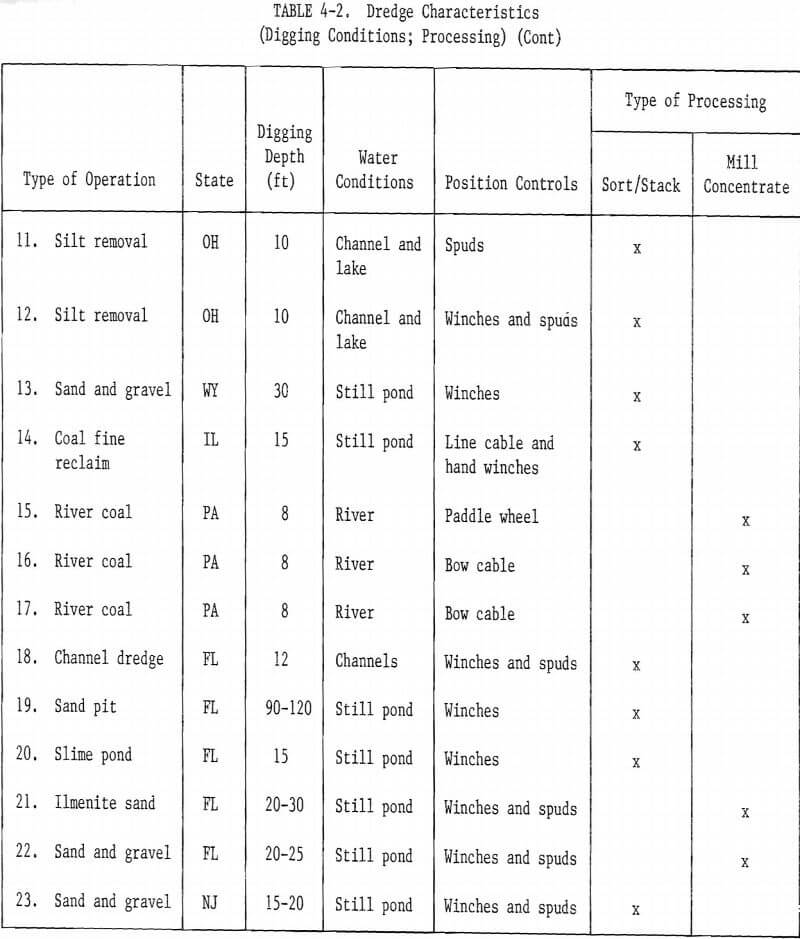

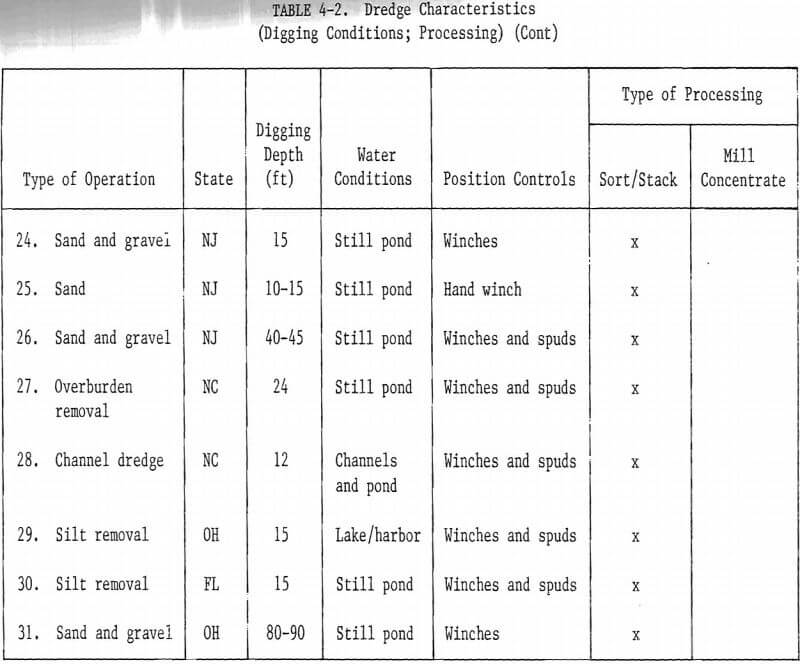

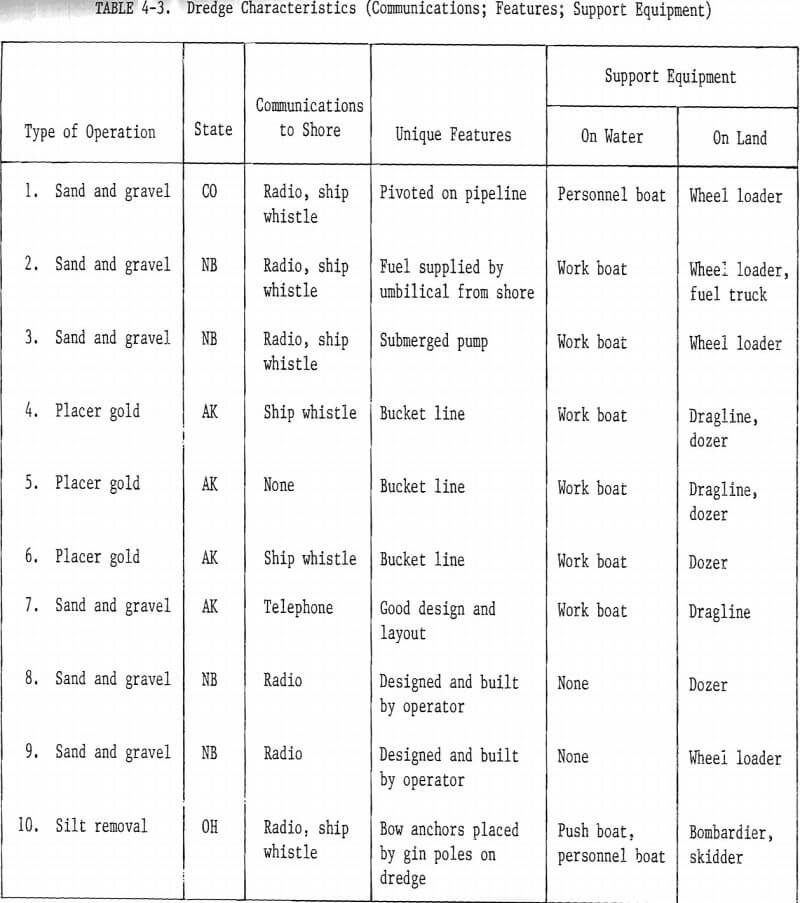

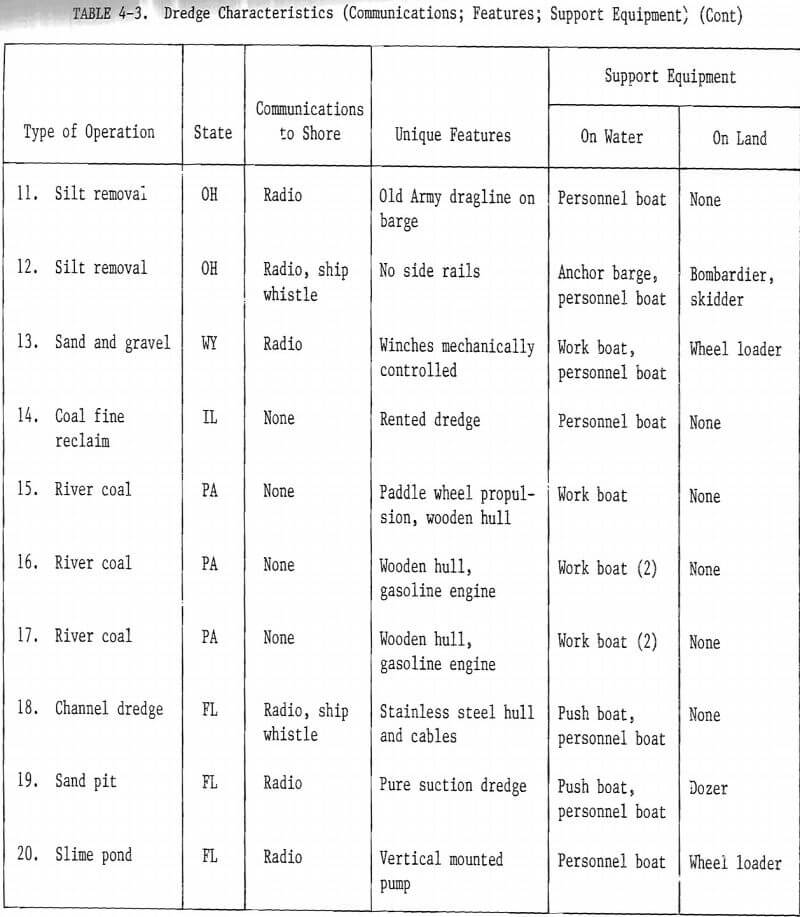

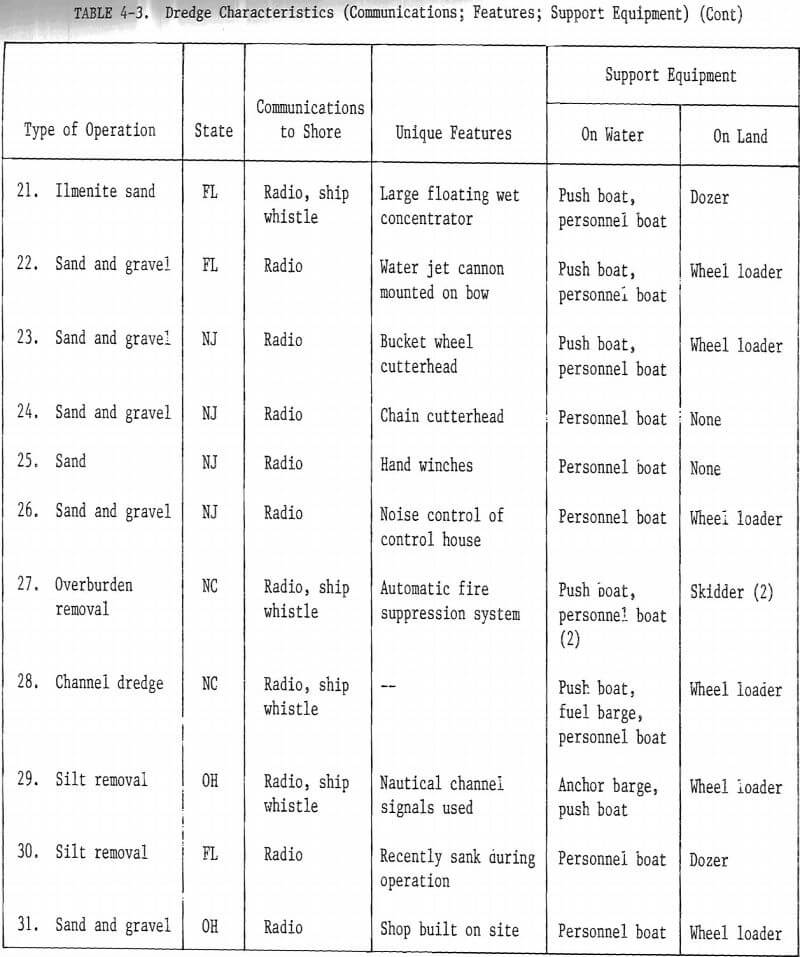

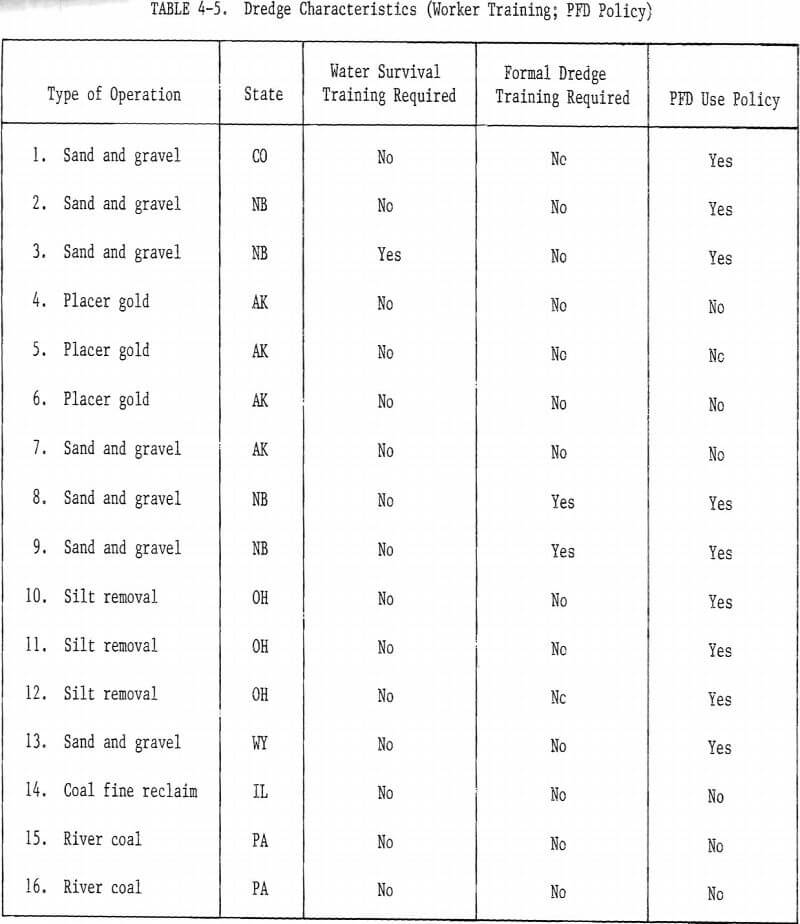

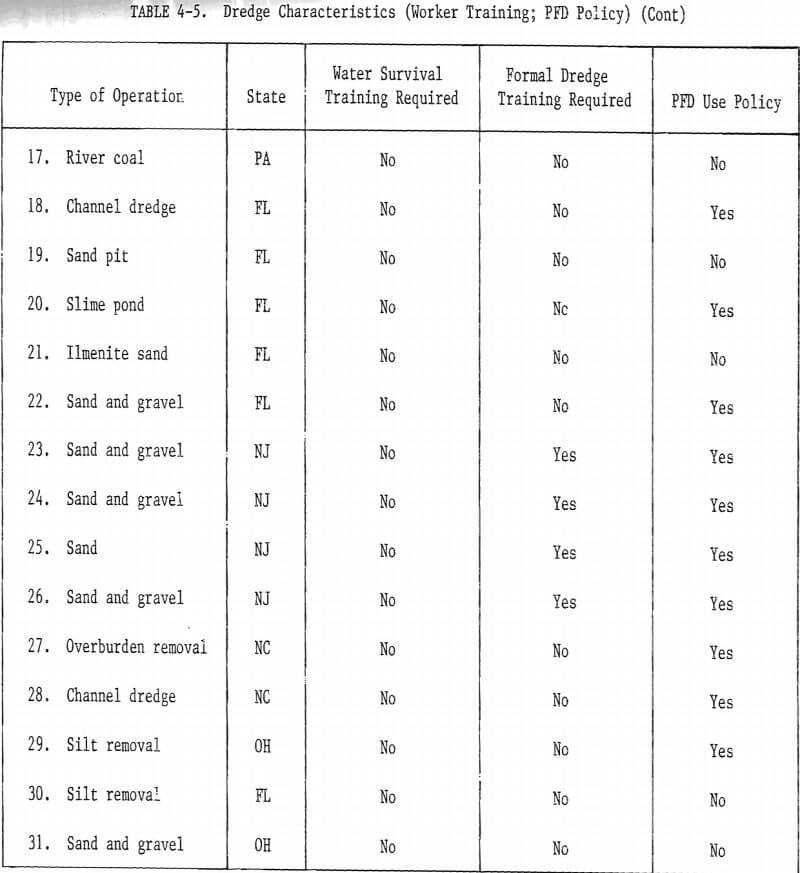

Tables 4-1 through 4-5 provide more information about each dredge visited.

Dredge Manufacturer and Consultant Visits

Manufacturer Visits

Dredge manufacturers contacted in the course of the program work were very cooperative. Visits for discussion of dredge design and operation safety were arranged with three of them (one, Ellicott, was visited twice) and with a manufacturer of components which are used by dredge manufacturers and by operating companies which construct dredges of their own design.

The manufacturers visited were:

- Ellicott Machine Corporation, Baltimore, Maryland.

- Dixie Dredge Company, St. Louis, Missouri.

- Dredge Masters International, Hendersonville, Tennessee.

- Pekor Iron Works, Columbus, Georgia.

There were several general conclusions drawn from the discussions with the three dredge manufacturers (Pekor does not manufacture dredges, but is a leading manufacturer of pumps for small dredges). These are explained in the paragraphs below.

Most of the dredges manufactured are for customers outside of the United States, thus the design and production work is done with little regard for MSHA and OSHA standards unless a customer includes appropriate requirements in the purchase specifications.

The manufacturing companies are far more concerned about product liability problems than about the relationship between safety and production effectiveness.

The companies are aware of 30 CFR 56 standards (sand and gravel) and of some OSHA standards. Two of them mentioned that a compliance problem is the noise on diesel-powered dredges. Only one of the companies was familiar with American National Standards Institute standard A, “Safety Requirements for Dredging,” but when it came up in the discussions, the other two stated that they intended to acquire and study the standard.

All three dredge manufacturers said that they believe that safety was primarily the responsibility of the owner/operator. The manufacturers are not indifferent to dredge maintenance and operation safety problems. They customarily use some form of deck railing, tread plate on stairs, “dimpled” deck plate to reduce slips, and guards on rotating machinery when dredges are “built for domestic use.” But they do not concern themselves greatly with safety designs and production processes which are “non-competitive.” For example, one company reported that a decision was once made to “box” the I-beams of the gantry with reinforcement bars to form a ladder so that a maintenance man could more safely and easily reach the top without using a portable ladder. An OSHA inspector advised that the ladder should be constructed according to OSHA standards, including a “back cage.” The company decided to leave the ladder off altogether. Another company reported that International Orange or Industrial Yellow hazard paint is not used anywhere in its dredges.

The manufacturers said that they receive very few criticisms from their customers on anything related to safety. They are, however, aware of many of the accidents which have occurred on dredges they constructed, and others. One company mentioned that a major safety hazard is hydraulic system oil sprayed on an engine exhaust manifold by a leaking line. An example of “flash explosion” in Mexico was cited. Another hazard discussed related to the application of heat to the flange holding the seal of a seized pump shaft, thereby causing the seal to explode. A letter which provides information on how to relieve the pressure and remove a seized shaft safely was sent to all “owners of record.”

Only one of the three manufacturers has a designated person who is responsible for safety matters and a safety program relative to the products manufactured. That company includes a brief “safety section” in its operating manuals and was engaged in preparing a new “safety handbook” for its future customers. The project was not complete because the company was concerned about “leaving something out” that would “open up a liability suit.”

All of the manufacturers have a field training program for dredge assembly, operation, and maintenance. All except the initial assembly and checkout, is an “extra” which the customer must include in his order.

Two of the manufacturers gave examples of poor hiring practices, inadequate training, and careless operating and maintenance procedures tolerated by dredge owners. One pointed out, in particular, that some maintenance and repair operations required power to the machinery. Power could not be “locked out.” This creates a hazardous condition the only solution to which, the manufacturer said, is “better training and supervision.”

Consultant Visits

Like the manufacturers and the dredge owners, every other person and organization contacted in the course of the program was very cooperative. There were many telephone contacts with persons associated with the dredging industry. Among those who were especially helpful were Mr. Mort Richardson of Symcon Marine (one of the founders of the World Dredging Association), Professor Larry Slotta of Oregon State University, Professor Wils Cooley of the University of West Virginia (principal investigator on a Bureau of Mines research project dealing with electrical hazards in mining), and Mr. George Watts, Executive Secretary of the Western Dredging Association. These persons are not “consultants” in the usual meaning of that word, but they provided information of the kind consultants can provide and many “leads” concerning dredges that might be desirable to visit.

Many of the persons contacted personally were also not consultants. Each of them added something of value to the information on dredge hazards. They are listed below, with a brief summary of the information of special interest they provided.

- Three MSHA Metal and Nonmetal Offices were visited. They were in Bellevue, Washington; Birmingham, Alabama; and Morristown, New Jersey.

Mr. Arnold Pederson, MSHA Mine Inspector at Bellevue, discussed his inspections of Alaska dredges and some of the unusual electric hazards observed. Most of these were because the workers were inexperienced and poorly trained to work in a very difficult environment.

Mr. Ron Hallmark, MSHA Mine Inspector at Birmingham, discussed the special efforts taken in the district to reduce drowning accidents. These emphasized, but were not limited to, the need to wear personal flotation devices while working over water and the need to have trained persons operating small boats.

Mr. Jim Toscana, MSHA Mine Inspector at Morristown, discussed special problems related to dredge fires in sumps; the “lack of respect” for 220-volt power lines demonstrated by the way in which power lines are handled and mounted; the need for water survival training; and the problems which often result from having only one boat in which to transport people to and from the dredge. He said that the principal sources of minor injuries were improper use of tools and slips and falls. He identified a special hazard on one dredge which resulted from capacitors leaking PCB.

- Two state-level officials concerned, as a part of their duties, with dredge safety were visited. One was in Nebraska, the other in Alaska.

Mr. Bill Laird, Program Monitor, Nebraska Department of Labor, had experience operating dredges on the Platte River. His office participates in investigations of fatal accidents. He arranged some dredge visits and took part in them also. He believes that most minor injuries on dredges are related to slips and falls. It was his view that the training, although usually limited to on-the-job type, was good, partly because the employee turnover rate is low at dredge operations and, therefore, employees “work up slowly”.

Mr. C. N. Cornwell is the Alaska State Mine Inspector. In his state employee turnover rates are generally high. The training needs are great and often the training programs are inadequate.

- Three dredging authorities were visited at universities, one in Alaska and two in Texas.

– Professor Ernest Wolff is director of the Minerals Research Laboratory at the University of Alaska and part-owner of a small gold dredging operation. It was his view that most accidents are due to the inexperience of workers and the harsh environment in which they work in Alaska, although he knew of very few injuries in his long experience with dredge operations. He helped to arrange a visit to an unusual and very excellent sand and gravel dredge operation near Fairbanks.

– Drs. John Herbich and Jack Lu of the Center for Dredging Operations, Texas A&M University, had done much research in dredging technology, but very little of it dealt with specific safety implications. They discussed the problems of dredge operations in waves and the use of a relatively new technology involving buoyant pipelines (lines encased in a foam rubber, closed cell, sheath). Many of the dredge operations with which they are concerned work in open seas or harbors. Collisions are a problem, but the most hazardous work is pipeline maintenance. They noted that the Corps of Engineers is very safety conscious and usually had larger crews than most private operators. Private operators, they said, do not require workers to wear personal flotation devices,, Two nonmining dredge sinking accidents were discussed in detail.

The Operating Engineers Union, Local No. 3, in Oakland invited a discussion of dredge safety. Workers represented by the union are employed on several types of dredges, mining and nonmining. The discussion centered on poor training (for the specific operation, that is, “task training”) and inadequate tools provided by dredge operators. There was also emphasis on poor supervision. Several cases were discussed in which a person was injured while performing an unsafe act which he had been specifically ordered to perform by his supervisor. Also discussed were two cases in which the union “pulled men off the job” because the supervisor had ordered work under unsafe conditions, specifically handling electrical cables in water.

Mr. David Henderson is the president of Erickson Engineering Associates, a dredging consulting firm. Discussions with him and his associate, Mr. Frazier, dealt primarily with the problems of operating dredges under new environmental control regulations. They suggested visits to several dredges with different digging devices in Florida, suggestions which were the genesis of several useful dredge visits.

MSHA Data Review

It was an early program decision to acquire accident and injury data from the Mine Safety and Health Administration’s Health and Safety Analysis Center (HSAC), in Denver. Two requests for data were made to the Bureau of Mines’ liaison officer to HSAC, Mr. Douglas Boyd. The responses were rapid and complete. The first request was for data on fatal accidents at dredge operations for the years 1973-1978. The second, made after the 1979 HSAC files were completed, was for data on 1979 fatal accidents and on nonfatal accidents for the years 1978 and 1979.

The data on fatal accidents were those for any fatal accident which could be identified with a mining dredge operation, HSAC provided a listing of the fatal accidents with a short narrative description of each, and later permitted a Woodward Associates research assistant to review, in the HSAC facilities, all of the MSHA fatal accident investigation reports which were of interest in this program.

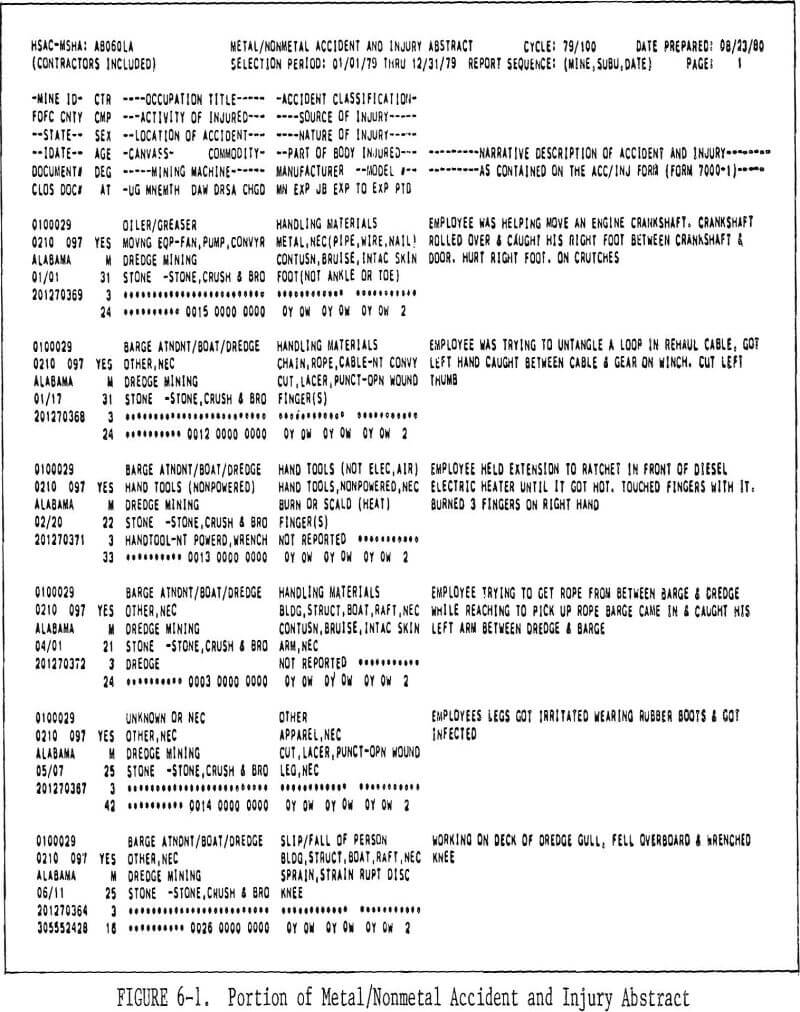

The data on nonfatal accidents were those which had a “location of accident” defined as “dredge mining” in the HSAC data files. HSAC provided listings which included a short narrative description of each accident (or illness). These short narratives usually contain all of the information reported on the MSHA Forms 7000-1. Unlike the fatal accidents, there are no formal MSHA investigation reports on these accidents, except in a very few special cases. The listings provided are illustrated in Figure 6-1 which is one page of the listing of 1979 metal and nonmetal dredge mining accidents (and illnesses). A separate listing was provided for coal dredge mining.

Fatal Accident Summary

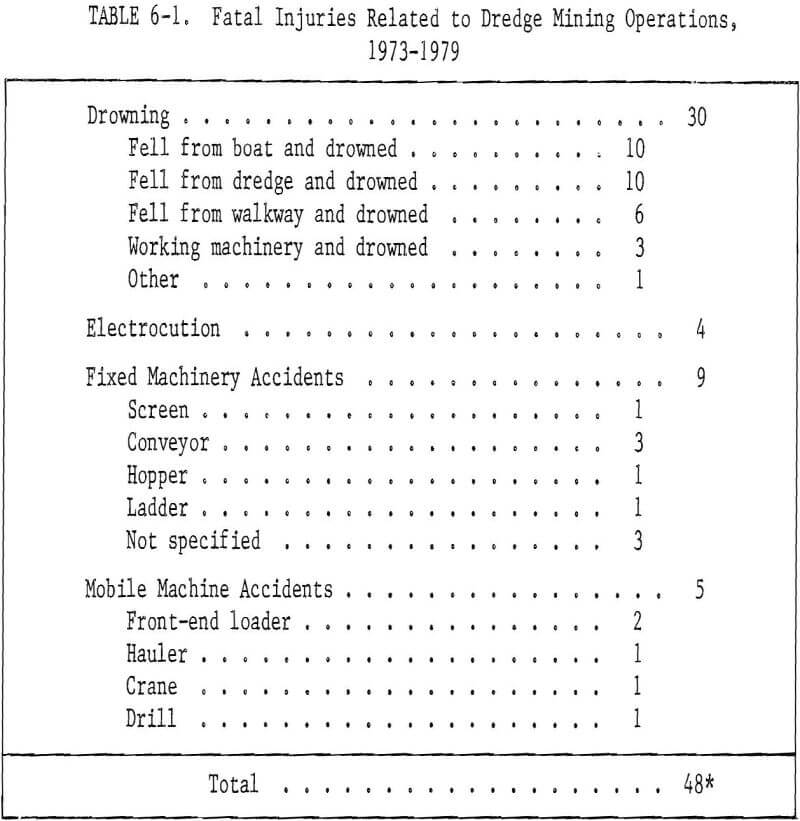

In the seven years 1973 through 1979, 48 persons were killed in accidents in dredge mining operations in the United States. Thirty of these people, or approximately 63% of the total killed, were drowned. Table 6-1 shows the number of fatal accidents in each of four general classifications.

The following paragraphs describe each of the 47 fatal accidents. The information was taken from the MSHA accident investigation reports. (The present MSHA policy is to investigate all fatal accidents and certain others in the 12 definitions of “accident” given in 30 CFR 50.2(h) which are considered to be especially serious.) For the convenience of the reader, the accident summaries are arranged, by classification, to correspond to Table 6-1.

Note: The classifications used may lead the reader to conclusions about the relative importance of electrical hazards which are not necessarily correct. Officials of the MSHA Safety and Health Technology Center (SHTC) in Denver and researchers working with Dr. Wils Cooley at West Virginia University pointed out that electrical shock may have been a factor in fatal accidents classified as “drowning” or “fixed machinery.” An MSHA-SHTC letter on this matter noted: “Several of the drownings cited [in the summaries below] were never fully explained and could have been the result of an electrical shock prior to falling into the water.”

4/3/73 Boat drowning 1 Victim was paddling a small work boat toward the shore, a distance of 120 feet, to turn on the electric power. Another boat, with 2 occupants, was towing a section of pipe to the barge. As the boats approached each other 1 of the 2 occupants yelled to the victim asking him if he had a sledge hammer in his coat. The victim, standing in front of the boat and holding a paddle in both hands, made no reply. He went over the side of his boat head first. He never surfaced. His body was recovered about an hour and a half later. Death was attributed to drowning. The victim was not wearing a life belt or jacket at the time of the accident.

11/5/74 Boat drowning 2 work, When the night shift dredge operator arrived to go to he noticed the victim’s pickup truck still in the parking lot. Upon further investigation he found the work boat against the bank of the dredge pond, unsecured. It was 150 feet away from the dredge. He started the boat and went to the dredge to look for the victim. The dredge had been shut down. He couldn’t find the victim so he went back to shore to get help. The victim’s body was found 5 days later. It was assumed the victim lost his balance attempting to repair or start the outboard motor. Death was attributed to drowning. The victim was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

12/3/74 Boat drowning 3 When victim did not arrive home, his wife called a co-worker to go look for him. The co-worker found the victim floating face down in the pond. The victim had apparently rowed a boat from the dredge to the shore. He either pulled the boat up on shore and then fell back into the pond or had gotten back into the boat and fallen over the side. The bank was sloped but footing was good.

1/21/75 Boat drowning 4 Victim was sent around the lake in a crew boat to pick up the second shift crew for transporting to the dredge. The dredge crew came to the main plant asking where the crew boat was to pick them up. A search was started immediately. The life vest, lunch box, oars and other items from the boat were found washed up on shore. The boat was later recovered in 20-25 feet of water and the victim was found 30 feet from the boat.

2/17/75 Boat drowning 5 Victim left the screen plant to start the dredge. His partner called the dredge later and received no answer. He repeated the calls every 15 minutes and received no answer. Victim’s partner finally went to pond bank to see what was wrong. He began to search for victim and noticed that the boat was neither at the dock nor in sight. The plant superintendent was notified and the search continued. A safety hat, thermos bottle and gas tank were found floating in the pond. A team of rescue divers was called in. Using grappling hooks, the divers recovered the boat and later that day recovered the victim’s body. Apparently no life jacket was worn at the time of the accident.

8/20/75 Boat drowning 6 When the victim failed to report for crew change, a call was made to the dredge. No answer was received. The foreman and several employees went to dredge to look for the victim. Later that day the victim’s body was found about ¼-mile from the dredge, entangled in a trout line. He apparently had slipped, or had failed to jump far enough, as he attempted to jump from the crew boat to a tugboat.

6/15/77 Boat drowning 7 The victim and another employee were in an aluminum rowboat on the dredge pond checking on a water pump unit which was malfunctioning. The victim put his hand on the 4-inch intake water pipe and screamed. The other employee immediately jumped out of the boat to the pipeline, which was 6 feet away. The victim fell out of the boat into 25 feet of water. Death was attributed to drowning and electrical shock.

1/26/79 Boat drowning 8 (2 victims) Four employees took a small boat from the dredge to shore. One employee put on and secured his life jacket, two others put their life jackets on but didn’t secure them, and the fourth placed his beside him in the boat. About 75 yards from the dredge the boat took on water and was swamped. Two of the workers, with unsecured life vests, jumped feet first into the water. As they entered the water their life vests came off and they went under and never surfaced. The other two employees stayed with the boat until help came. The two victims were found after dragging the pond. Artificial respiration was given but one victim was pronounced dead on the scene and the other at the hospital.

6/22/79 Boat drowning 9 The victim, working on the dredge, returned to shore for a cooler of water. A mechanical problem developed at the screening plant and the maintenance man went to inform the victim. He saw the work boat caught on the dredge anchor cable, motor running and empty. The maintenance man couldn’t locate the victim, so he went for assistance. Dragging operations were begun and the victim’s body was recovered. Apparently the victim lost control of the work boat, ran into the dredge and fell, or was thrown, overboard. The victim’s life jacket was found on the rear seat of the work boat.

2/18/73 Dredge drowning 1 The victim, night captain on the dredge, was apparently standing on an oil drum welding on the dredge when he fell overboard. His body was found the next day after dragging operations were begun. He was not wearing his life jacket at the time of the accident.

10/15/73 Dredge drowning 2 The victim and his co-worker were instructed to stay at the end of the shift. The victim’s co-worker was to check the shipping tickets and the victim was to turn off the dredge pump at 5:30. About 6:00 the co-worker noticed the dredge pump was still running. He turned it off and searched the area until 8:00 looking for the victim. Unable to find him, he went for help and the victim’s body was found about 10:00 near the dredge platform. Apparently the victim was attempting to cross the walkway to the dredge platform and slipped and fell into the water. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

12/1/73 Dredge drowning 3 The derrick operator noticed a worker at a safe location on the west side of the barge outside the railing of the cargo space. About 45 seconds later he couldn’t see the worker. He went to investigate and saw the victim floating face up and motionless about 20-25 feet from the south end of the barge. He threw a rope to the victim but the victim made no attempt to catch it. The derrick operator went for help and when the shop men arrived the victim had disappeared in the water. The body was found approximately 3 hours later. Apparently the victim had been cleaning the barge, lost his footing and fell in the water. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

7/14/74 Dredge drowning 4 Victim was helping to measure the holding line cable for the clamshell bucket when he either slipped or stumbled and fell against the single chain guard. The chain pulled loose from the hook and the victim plunged head first into the sea well. The dredge attendant attempted to reach the victim but failed. The victim went under and never surfaced. Victim was not wearing a life belt or jacket at the time of the accident.

9/23/74 Dredge drowning 5 The victim and a co-worker were inspecting the cable on a barge. They placed the cable so that when the barge moved forward the cable would raise out of the water and slide over the deck of the barge. A splice in the cable hooked the front of the barge, causing the barge to slide further under the cable. Victim was knocked into the water by the cable as it swept over the deck. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident and did not know how to swim.

6/13/75 Dredge drowning 6 The victim stepped on a kevel at the stern of the dredge slipped and fell into the river between the dredge and sand barge, just forward of the classifier barge rake. He fell in where it was almost impossible for anyone to get out, due to the swift current. The current took him under the rake of the classifier barge.

7/20/75 Dredge drowning 7 The victim went midship to move the ore barges alongside the dredge with an electric-powered cable winch. At 9:45 the pilot saw the victim standing on the port side of the dredge with his foot on the winch cable. At 10:00 the dredge operator didn’t see the victim and a search was started. At 10:30 he was declared missing and the authorities were notified. At 3:40 the next afternoon the victim’s body was found alongside a sand bar. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

8/30/75 Dredge drowning 8 Victim reported to work and picked up a small personnel boat to get to the dredge. Later he reported by radio that he had motor trouble enroute to the dredge and asked for assistance. When assistance arrived, the victim was missing. A search was started on the dredge and barges and he couldn’t be found. On September 2 the victim’s body surfaced under the bucket ladder when it was lifted for servicing. He had no life jacket on.

5/27/76 Dredge drowning 9 Victim was moving a portable pump from the barge to the ladder end of the dredge. Apparently he returned to the barge, picked up the suction hose and carried it to within 35 feet of the ladder end of the dredge. It was found partly in the barge and partly in the water and the victim couldn’t be located. A search was begun and the victim was found later in the day in approximately 35 feet of water, near the ladder end of the dredge. Apparently he had fallen off the dredge. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

7/7/78 Dredge drowning 10 The victim and a co-worker were working together. The co-worker went to shore for a drink of water. Victim apparently had a diabetic attack and fell or jumped into the water. The co-worker came back, saw him and asked him if he needed help. The victim nodded his head affirmatively, so the co-worker entered the water. He grabbed the victim twice and both times the victim started fighting him. He had to give up because he was afraid that he was going to drown also. Victim went under and never surfaced again. Co-worker went for help and the body was later recovered. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

7/2/73 Walkway drowning 1 Victim and his co-worker, after being unable to correct a problem they were having with a pump on the dredge, decided to walk to shore. Victim followed behind his partner on the walkway. The partner turned around when he reached the bank and saw the victim let go of the handrails and fall into about 40 feet of water. Victim surfaced once and yelled for help. His partner tried to rescue him but failed. The body was recovered ½-hour later. The victim was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

5/25/75 Walkway drowning 2 An employee on shore noticed that the dredge was pumping only water. He notified the office by radio and went to look for the dredge operator. Three other men arrived and they all searched for him. A motorboat was found tied to the third float, at a bend in the pipeline, with the motor still running, One of the men noticed one of the anchor ropes had slack in it. He pulled on the rope and the victim surfaced. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident and could not swim. Apparently he fell from the pipeline, struck his head and drowned.

4/9/76 Walkway drowning 3 A loader operator noticed a barge drifting, but thought that the victim was attempting to move the barge or that the anchor rope had parted. He started out on the walkway and saw the victim about 10-12 feet from the barge, not wearing a life jacket, in the water. The victim was thrashing around and yelling for help. The loader operator was unable to swim so he tried to pull the victim in with an anchor rope but the victim told him he was caught in the rope. The operator went for help. When he and two employees returned, the victim was face down in the water. One of the employees swam out and cut him loose. Artificial respiration was administered and continued until victim was pronounced dead by a doctor.

8/27/76 Walkway drowning 4 The victim apparently fell in while attempting to walk on the pipeline from the dredge to shore. The dredge crew heard him yelling and went to investigate. They found him in the water, threw him a doughnut-type life preserver with line attached, and saw him catch it. He then released it and went under. The body was recovered after dragging operations were begun. He was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident.

1/11/77 Walkway drowning 5 Victim was instructed to check the tide levels in the pond. He asked if he should check the dewatering pumps and was told not to. Two men usually checked them. Apparently he decided to check them anyway and fell into the water while walking a pipeline to one of the pumps. He wasn’t wearing a life jacket.

1/13/77 Walkway drowning 6 The victim attempted to walk a 10-inch, 40-foot long pipeline from the dredge to the shore in the rain. He apparently fell in. The victim was not wearing a life jacket at the time of the accident and did not use the boat that was provided for transportation to the shore.

11/12/74 Working- machinery drowning 1 The dredge operator noticed that the sand had stacked up to the conveyor belt and went to see what had happened to the loader operator. He couldn’t be found. Some truck drivers helped in the search and one of the drivers noticed an oil slick on one of the ponds. Two divers were brought in to search the pond. The loader was located right away and the victim was found 5 hours later. Death was attributed to drowning.

12/4/74 Working machinery- drowning 2 Victim and co-worker were changing the drive sprocket and chain for the port side load-out conveyor belt. They were working from the conveyor belt when the belt was inadvertently started by the starboard chute operator. The victim was thrown overboard and the co-worker managed to hold on until the belt was stopped. The victim’s body never surfaced and was found the following day. Victim was not wearing life jacket at the time of the accident.

5/14/77 Working machinery drowning 3 The victim was dredging sand and gravel from a pond with a dragline. Another employee noticed the dragline had entered the water. He called to a third employee and they attempted to rescue the victim, who was treading water. The body was later recovered in about 15 feet of water, about 40 feet from shore. Apparently the digging lock was broken and this allowed the dragline to pull itself into the pit.

3/14/73 Other drowning 1 The victim was performing various duties assigned to him when he was last observed by the plant operator. He was last seen about 30 feet from the pond. At the regular start-up time, about 20 minutes later, the plant operator realized that sand was not being pumped from the dredge. He started toward the dredge and observed the victim floating face down in the water between the bank and discharge pipe. He removed the victim from the water and telephoned for help. Victim was not wearing life jacket at the time of the accident.

12/30/75 Electrocution 1 The victim saw a baby rabbit run into a stack of irrigation pipes. He tried to get the rabbit out of a pipe by lifting it into a vertical position. The pipe slid away from him. He called to another employee to help him and together they lifted the pipe up. It contacted a 7,200-volt power line. One employee “blacked out” and fell. The victim was observed bent over and staggering before he fell. He was given artificial respiration and oxygen when the ambulance arrived. He was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital.

7/14/77 Electrocution 2 Apparently the victim was attempting to add water to the brine tank by standing on the ledge of the tank. He evidently slipped and fell against the electrode or leaned against it. He was found lying against the tank, the hose still running. No pulse could be found. He was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital.

10/28/77 Electrocution 3 Victim broke a bulb in a socket while trying to replace it. The winch operator later heard moaning sounds and an electrical arcing and found the victim crouched with his arm raised into the lighting fixture. He pulled the crane’s power cord from the outlet and went for help. Victim was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital.

6/9/79 Electrocution 4 Victim was electrocuted while attempting to free a high-voltage power cable from the bottom of the dredge pond. Victim noticed a section of submerged trailing cable covered with sand near the shore. While using a dozer to pull the cable, another worker heard an electrical crackling sound from the dredge and the dredge appeared to be drifting away. Two of the phase wires and the ground conductors were pulled loose at the connection to the dredge and came in contact with the dredge frame. This created a short-circuit, phase-to-phase condition which energized the dredge frame and the pond. Victim was standing in about 2½ feet of water; he grabbed his chest and fell forward. It was estimated that the duration of the short-circuit condition was a few seconds, until the circuit breaker on the 480-volt side of the transformer opened and interrupted the short-circuit condition. The victim was pulled from the water and given mouth-to-mouth resuscitation until the county rescue squad arrived a short time later. However, the victim did not respond and was pronounced dead on arrival at a local hospital.

3/10/73 Fixed machinery 1 (screen) The crew started to change a screen panel in the screening tower. The victim was working on the deck below. The new panel was hoisted from the deck to the tower and placed upright along the work platform handrails. The screen slipped and hit the tower and the swaying of the dredge caused the screen to slide under the mid-rail and fall on the victim’s head, killing him instantly.

5/22/75 Fixed machinery 2 Victim was at the entrance of the raw surge tunnel, opening the valve on the water line used to wash down the tunnel, when the aluminum water line separated at the valve. The force of the water pushed victim down the tunnel and under the conveyor belt. His co-worker went down, into the tunnel and pulled him from under the belt and went to get help. He was treated for shock and taken to the hospital. He died later of respiratory failure.

5/28/75 Fixed machinery 3 Victim was checking the product flow and the bearings of the main roller when last observed. About 10 minutes later the dredge oiler operator received a call from the foreman telling him that the product flow on the discharge end of conveyor 1 had stopped. The dredge operator shut down the dredge, the sand dewatering plant and the overland conveyor belts. He started walking out the overland conveyor belts and heard the victim shouting for help. He found him face down with his left leg caught between the belt and the drum pulley and partially covered with gravel. He tried to free the victim and couldn’t. He went for help and the victim was removed. Victim was transported to the hospital and died there of hemorrhagic shock. While he was still conscious, he stated that he had slipped and fallen onto the belt.

1/23/78 Fixed machinery 4 A truck driver from the plant noticed that the conveyor belt had stopped running. He went to check on it and found the victim caught in the tail pulley of the conveyor. The foreman was summoned by radio and when he arrived the victim was dead. It was assumed that the victim was trying to remove ice from the pulley. Death was attributed to massive injuries to head, right arm and chest.

2/15/78 Fixed machinery 5 The victim and a co-worker went to free material that was hung-up in the hopper. The victim went out over the bridged material to prod it loose. The material collapsed and the victim was buried. The co-worker grabbed a cross-beam and was covered to his waist. He was helped out. The victim’s body was recovered an hour later. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

12/6/78 Fixed machinery 6 (ladder) A dredge operator and victim were climbing to the top of the screening plant when the operator heard, but did not see, the victim fall. He turned around and saw the victim was lying on the ground. The victim complained of injuries and asked to go home. The victim’s wife later took him to the hospital where the doctor performed an operation. He died in the hospital of a blood clot.

7/28/75 Fixed machinery 7 (not specified) Victim was attempting to install drive belts on a ladder hoisting unit while the unit was under tension. After loosening the bolts holding the pillar block bearing, the weight of the dredge ladder on the hoisting unit caused the mechanism to reverse. In doing so, the V-belt sheave on the hoisting drum drive broke, striking the victim in the face and fracturing his skull and neck vertebrae.

6/23/77 Fixed machinery 8 (not specified) Victim was found sitting on a bucket, about 15 feet from a cast iron winch. He had blood on his head and elbow, but couldn’t remember what had happened. There was a pool of blood near the winch on which he had apparently struck his head. He was transported to the hospital. He died that night of a severely fractured skull. On other occasions he’d been dizzy and at the time of the accident he wasn’t wearing his hard hat.

12/9/77 Fixed machinery 9 (not specified) The victim and another employee were shoveling sand into burlap bags for personal use. They had a pickup truck backed to the sandpile and the sand started sliding. One employee jumped free and the other was pushed into the box of the truck and covered with sand. Death was due to suffocation.

5/22/78 Mobile machine 1 (front-end loader) Victim was operating a loader on top of a dike. A truck driver, who was dumping a load, looked in his rearview mirror and observed the loader rolling over the edge of the dike. It made a complete turn and stopped about 20 feet from the top of the 10-foot high dike, resting on its side. The truck driver ran to the loader and saw victim trapped in the cab. He radioed for help and victim was freed from the loader. He was pronounced dead at the scene from massive chest injuries.

7/17/78 Mobile machine 2 (front-end loader) Victim walked behind a front-end loader that was backing up and was run over. The front-end loader operator stated that he had checked behind his loader before he got in and began backing up. The machine was equipped with a back-up alarm and it was in good working order.

7/27/74 Mobile machine 3 (hauler) The victim, driving a loaded truck, failed to stop at a railroad track as a railroad switch engine and way-car were going by. The train was using all necessary warning devices at the time of impact. The train hit the truck just behind the cab in the front part of the dump box. The cab was torn from the truck and landed 200 feet from the crossing. Victim was still in the cab with his feet on the dash and his head hanging out of the window on the driver’s side. He was taken to the hospital and died 2 hours later of massive internal injuries and broken neck and back.

11/17/76 Mobile machine 4 (crane) The dredge crew was moving a dredge anchor while the victim was operating the crane. One employee hooked onto the anchor buoy and another operated the vessel. As the anchor was raised, the beam swung to the right and the victim signaled to move the vessel. At this instants the victim looked at the butt of the boom and turned away as the boom fell and pinned him in the operator’s seat. He was freed, transported to the hospital and pronounced dead on arrival with massive internal injuries and a severed spinal column.

11/17/78 Mobile machine 5 (drill) Victim was helping drill test holes when he reached toward the top of the moving auger stem with his left hand. His hand and arm became entangled around the auger. His neck and shoulder was pulled against the drill frame. His co-workers determined that he was dead and summoned the proper authorities. Death was attributed to multiple fractures and soft tissue trauma.

Nonfatal Accident Summary

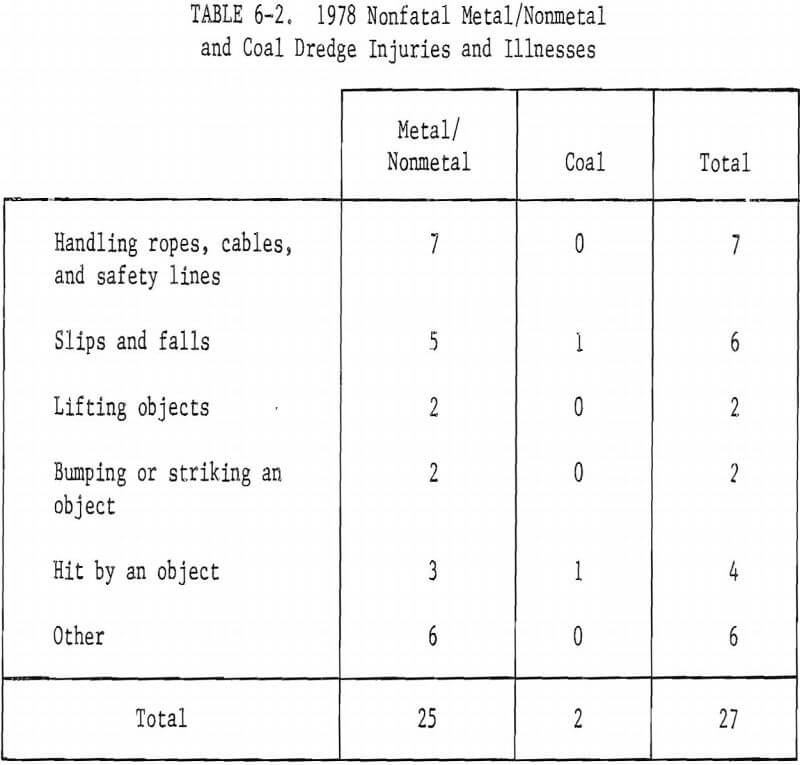

Table 6-2 shows the numbers of nonfatal injuries (and illnesses) reported to MSHA by dredge mining operations in 1978. The accidents are separated into six classifications and identified with either metal and non-metal operations or coal operations.

Only 27 nonfatal injuries and illnesses were reported in 1978, a year in which there were 7 fatal accidents in dredge mining. The ratio of nonfatals to fatals (3.86:1) is very small compared to those ratios for many other types of mining. A part of the reason is that dredge mining is less hazardous than most other types. Another part of the reason may be in reporting deficiencies. During the field visits to dredge operations it was judged that minor injuries are less likely to be reported than those which occur, for example, in an underground coal mine. Yet another part of the reason may be related to working over water. As noted in earlier sections of this

report, falls into the water (from dredge, boat, barge or pipeline) are relatively frequent, but most do not produce any injuries and are not reported. (“A fall into water” is not included among the 12 elements of “accident” definition in 30 CFR 50.2.) A fall into water is generally less likely to produce an injury than a fall onto a hard surface. On the other hand, a fall into water by a non-swimmer who has no life jacket (personal flotation device) is more likely to produce a fatality than a fall in which water survival is not a factor.

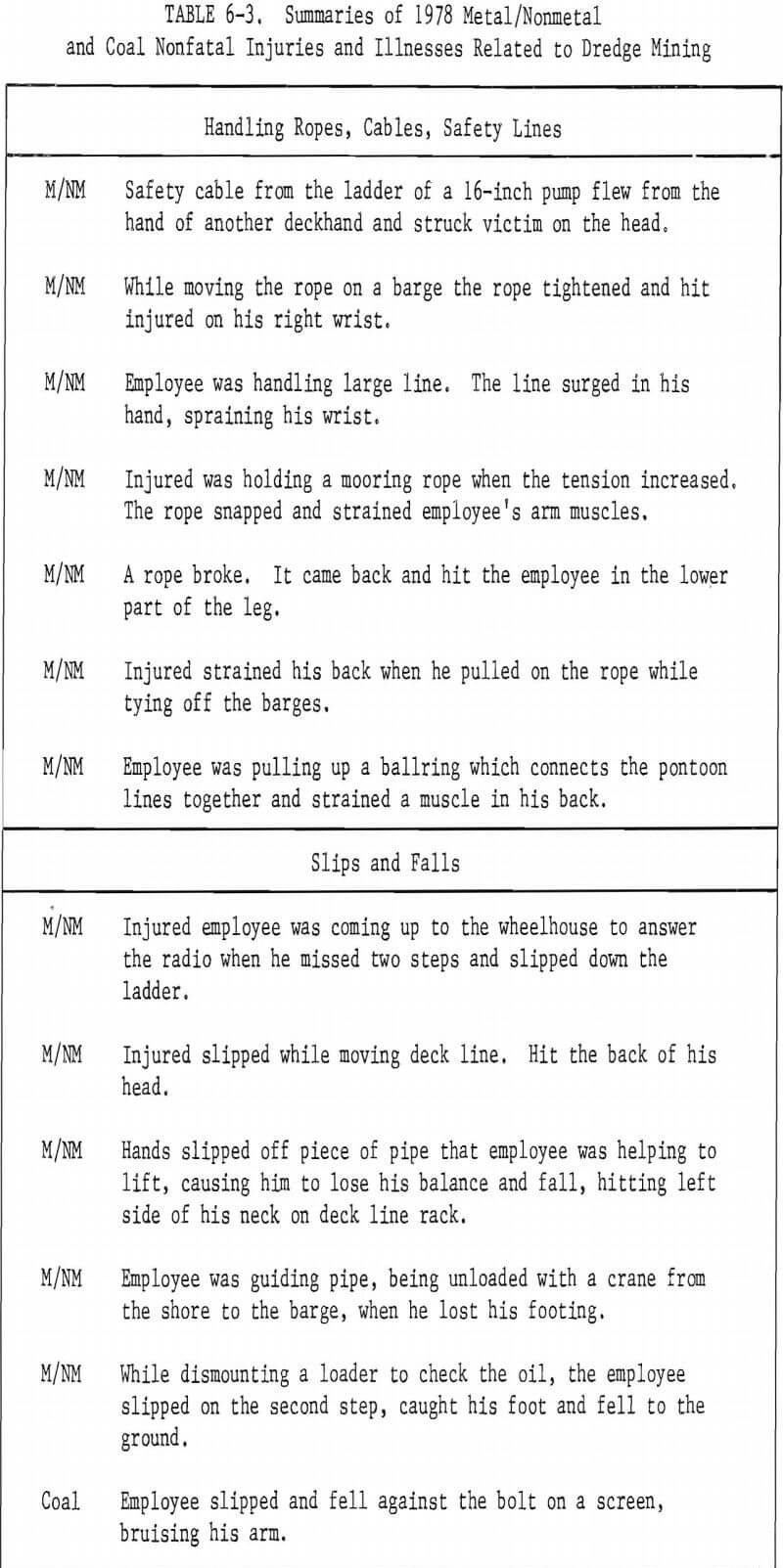

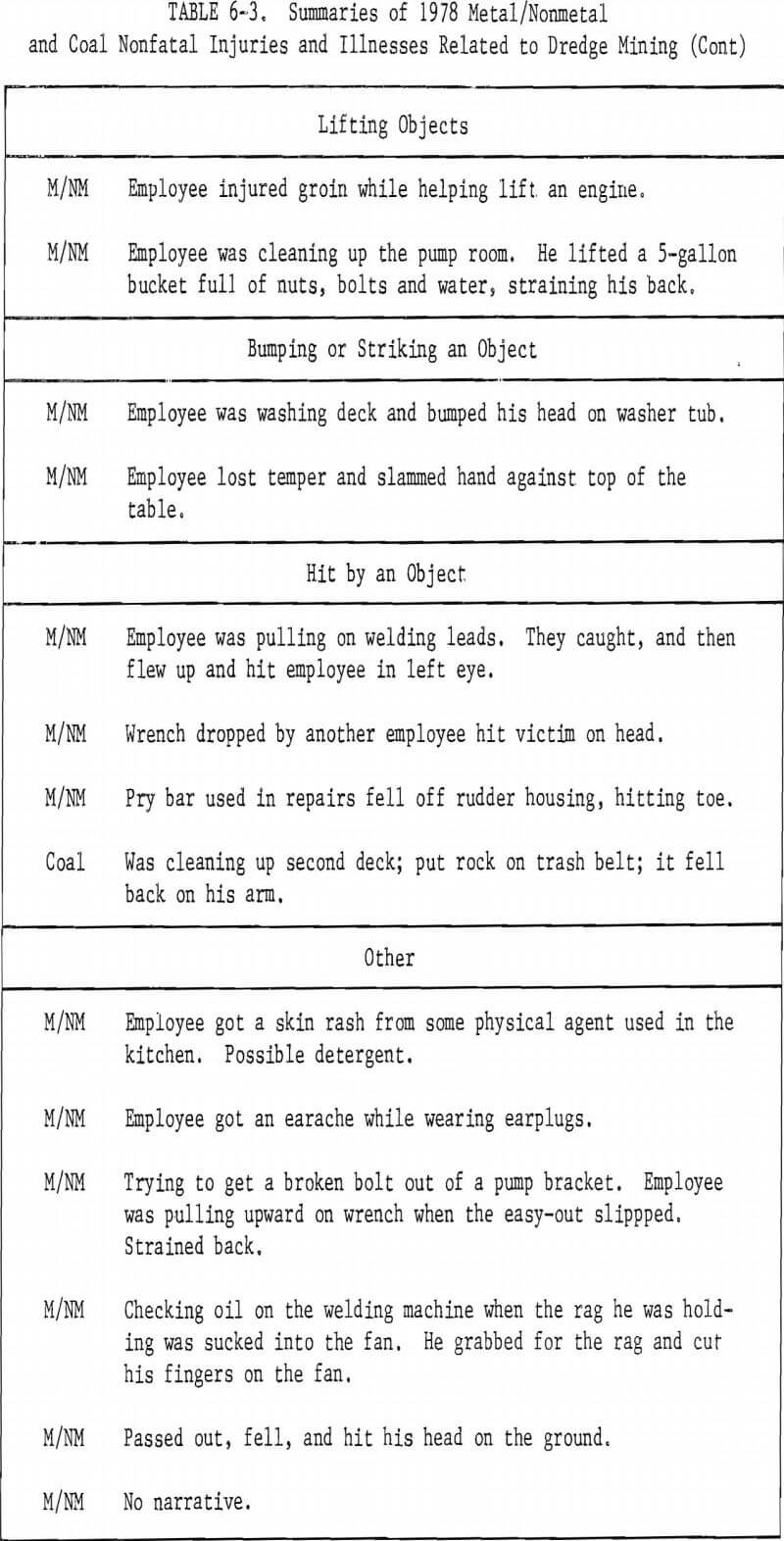

Table 6-3 is a summary of each of the 27 injuries and illnesses. The information was quoted from the HSAC abstract or was paraphrased for clarity. It is, in short, a dependable reflection of the information provided to HSAC on the MSHA Forms 7000-1 submitted by dredge mining companies during 1978.

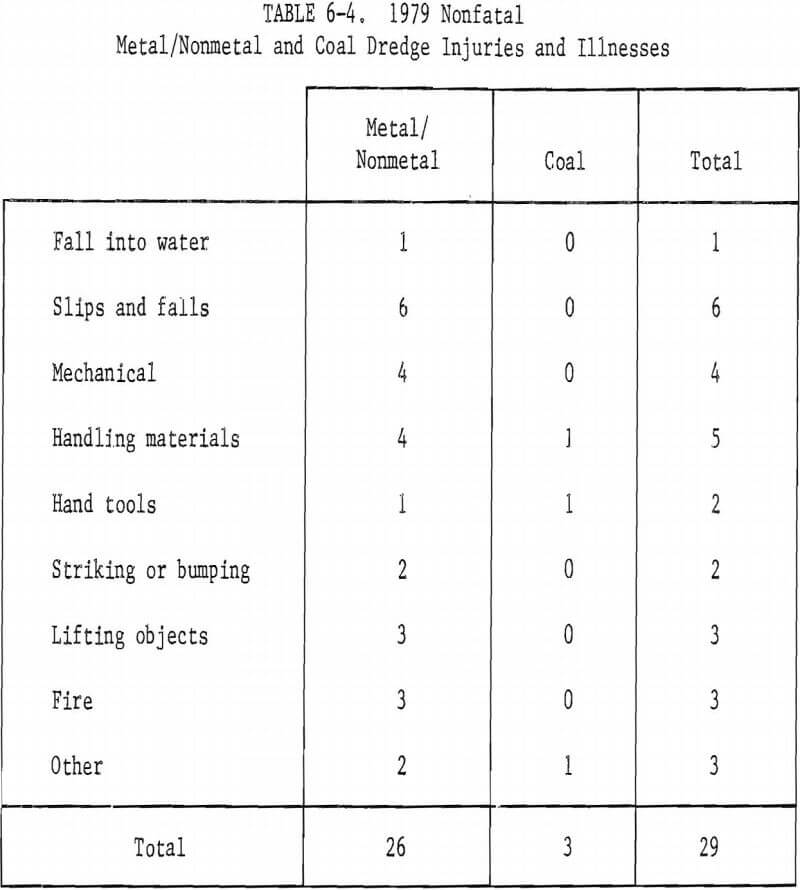

The 29 nonfatal injuries and illnesses reported in 1979 are separated into 8 classifications on Table 6-4. The total in each classification has subtotals for metal and nonmetal and for coal.

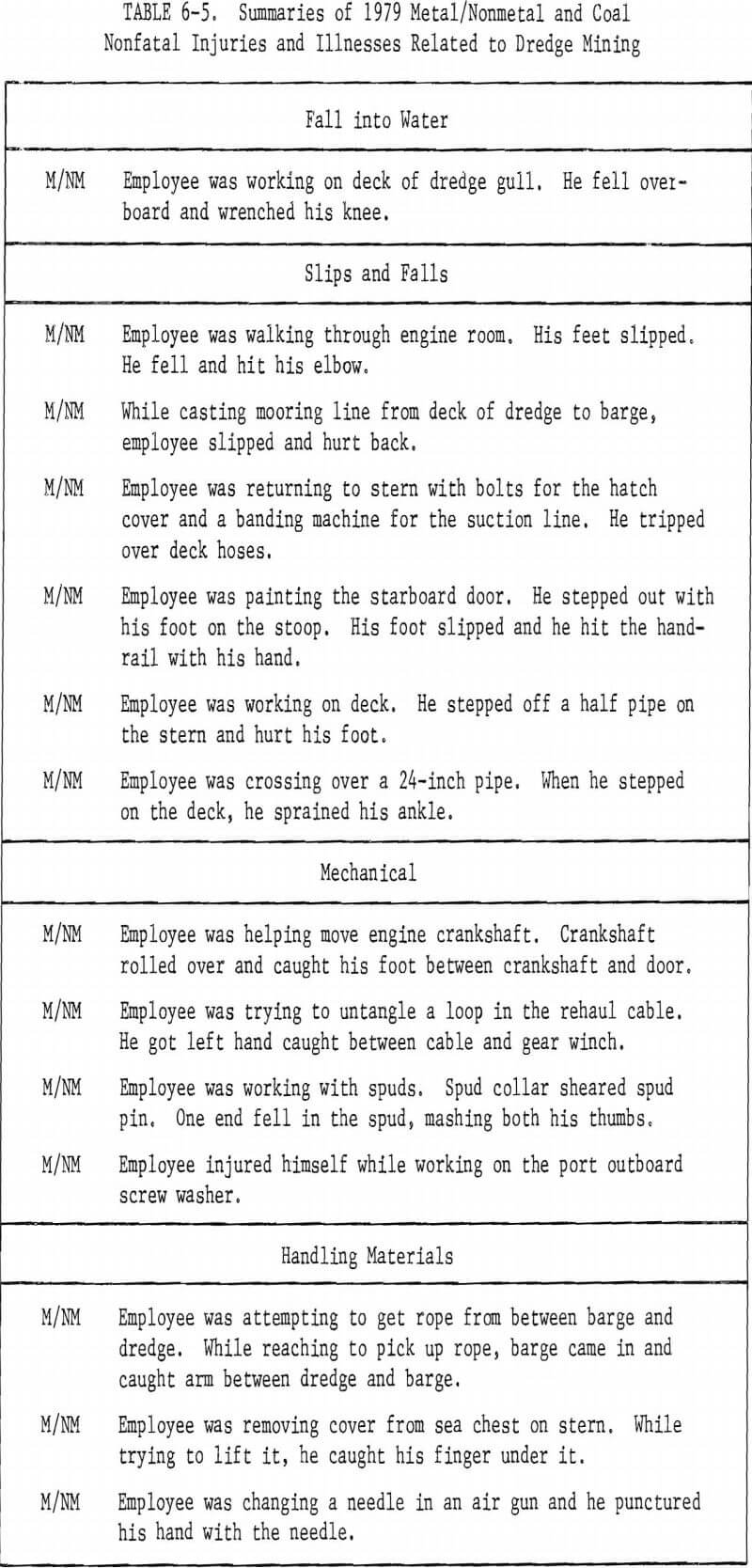

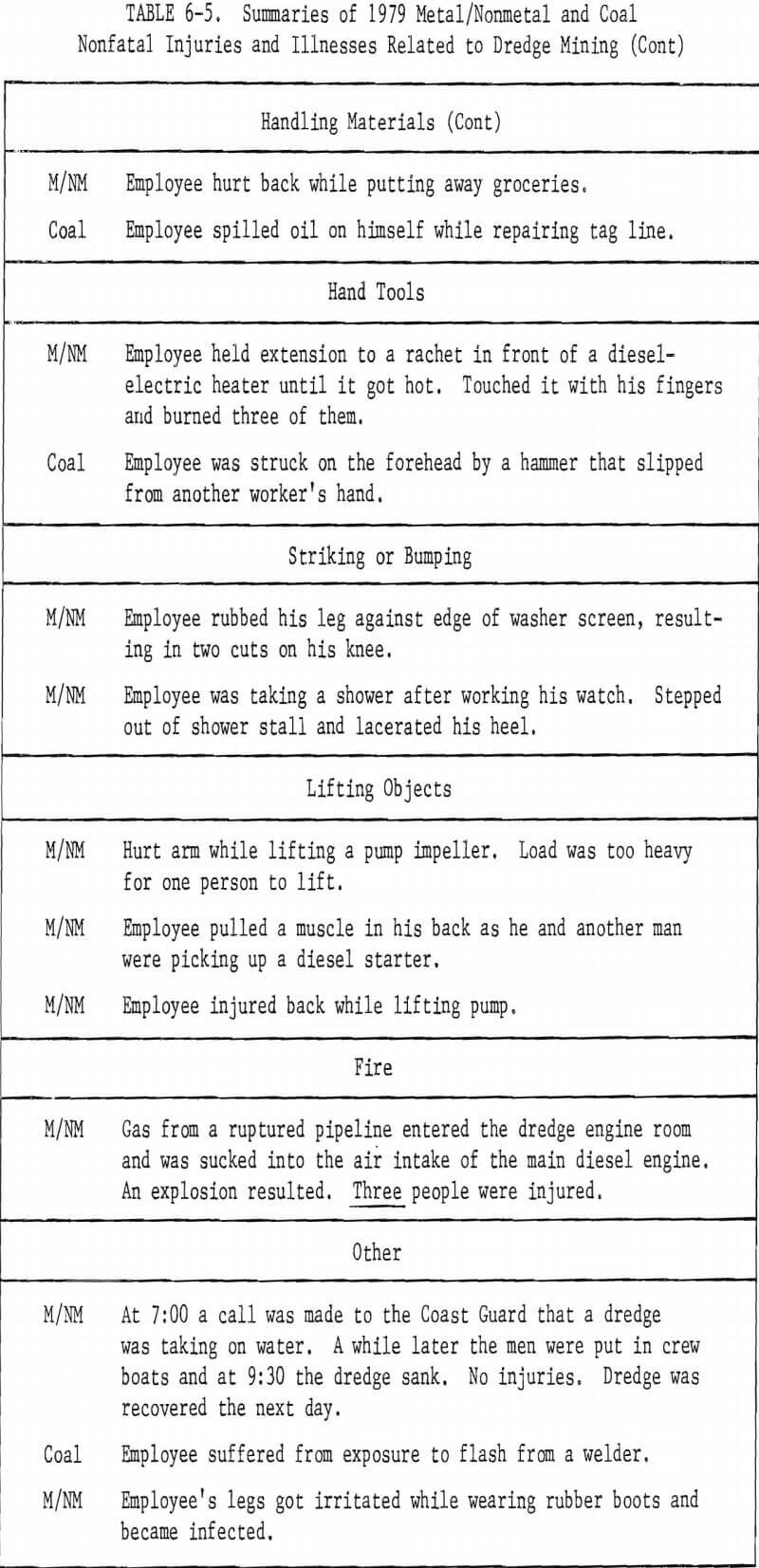

Table 6-5 is a summary of each of the 29 injuries and illnesses for 1979. The information is from the same sources as that for 1978.

Literature Review

A literature search was conducted for items related to safety and hazards in mining dredge operations. Through the University of Nevada library, several computer data banks were searched, using appropriate descriptors or identifiers. The banks searched included Compendex; Information Service in Mechanical Engineering; Society of Automotive Engineers; National Technical Information Service; Oceanic Abstracts; and Maritime Research Information Service. Using the facilities of the Nevada State Library, a manual literature search was made of U.S. Bureau of Mines publications, Applied Science and Technology Indices, and mining and dredging periodicals. Contact was made with the World Dredging Association to identify articles, whether published or not, which deal specifically with dredge hazards and safety practices. A visit was made to the Center for Dredging Operations, Texas A&M University, for the same purpose.

The searches produced very little published information specifically about dredge mining hazards or dredge safety programs and practices. Fifty-five articles, reports, regulations, and training documents (including two films) were reviewed. The most useful of these, and those which are recommended for review by others who may study mining dredge safety.