The sampling and estimating of the orebodies in a mines have been made a part of the work of the geological department. The wisdom of this assignment is apparent, considering the organization of that department, the nature of its records, and the scope of its regular work. In the first place, the district is divided into units of two or three mines each and a geologist is assigned to each group. His trips to all the working places are frequent and he follows the mining operations closely. His notes are graphic and detailed. In the office, he posts his notes on the standard maps and sections and on special maps for correlation purposes. With the approval of the chief or assistant chief geologist, he recommends development work underground and watches its progress. This gives the geological department a precise knowledge of the character of each orebody.

Sampling is done by one or two samplers at each mine working under a chief sampler stationed in the geological office. The chief sampler has access to all the office maps and is in frequent consultation with the geologists; his instructions to the samplers are issued with the approval of the chief or assistant chief geologist. Not only is it important that the geologic information be used to direct the sampling but the reports of the samplers and the records kept by their chief are useful to the geologist, who needs them in his work of estimating ore reserves and deciding on recommendations for development work. The sampler, moreover, is at the mine every day and makes a daily report, which keeps the geologist in close touch with the progress of development work.

The sampler is attached to the mine office and thus comes under the jurisdiction of the operating department. In fact, any special orders prepared by the chief sampler are submitted to the general superintendent, after approval by the geological department. The mine foreman may also order certain special samples taken for him, if those required by the sampling department do not fully meet his requirements. The samplers are selected by the geological department with the approval of the operating department; they are generally young men with some technical training. The cooperation between the operating department and the geological office, which has long existed in Butte, makes this organization of the sampling branch practical and efficient.

THE OREBODIES

The ore deposits to be sampled are veins varying in width from a few inches to 50 or 60 ft. Steep dips predominate although dips at all angles are found. The veins belong to a complex system of fissuring of different ages and present a wide variety of vein filling. Some exposures present a hard mineralization of fairly uniform character from wall to wall, but many contain bands of altered granite, crushed in the process of faulting and carrying only scattered particles of metallic sulfides. A large part of the orebodies consist of veinlets of chalcocite or enargite traversing granite in such close succession as to make valuable ore of certain masses. Throughout the district, however, the structural features are fairly well defined and have served as a guide to the sampling.

STANDARDIZATION

The first step under the present organization was to classify all the probable occurrences to be sampled into a few standard types. Four types were found to be enough to cover all exposures in the faces of drifts; they are: Uniform ore; part good and part low grade; part good, part low grade, and part waste; narrow streak good but balance doubtful.

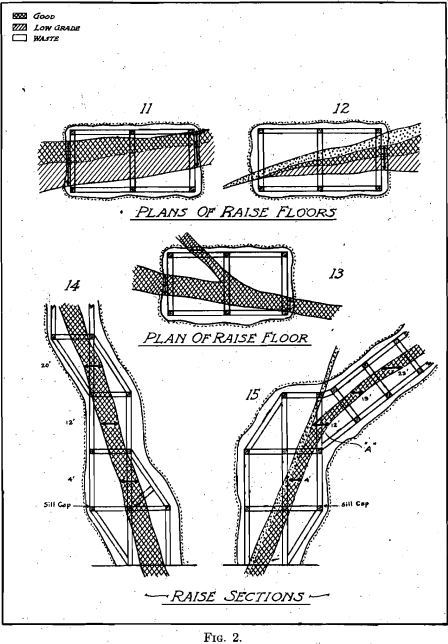

The types are shown on drawings on a fairly large scale, together with some plans and sections of crosscut exposures and type sections of raises. The required sampling is indicated definitely on each sketch and a colored print of each is given to each sampler. This serves as a basis for all the sampling and, with certain written instructions accompanying each print, the results from all the mines are the same and the personal equation eliminated. Figs. 1 and 2 show these standardization charts.

UNDERGROUND METHODS

The sampler is required to examine each place to be sampled and decide to which type it belongs. He then takes the required number of samples, at breast height, along a horizontal line, irrespective of the dip of the vein. He also measures the width horizontally. This measurement is correct because the longitudinal sections upon which the ore blocks are laid out are projections on vertical planes. The ideal cut, or channel, across the face of the drift is impractical, from an operating point of view.  Too much time would be lost if the miners had to wait while the sampler laid out and chiseled a neat groove across the vein; indeed, the varying degree of hardness of parts of the vein would make such procedure difficult. The same results are obtained by the use of the sampler’s pick. The sampler takes equal amounts of material from points along a predetermined line and catches it in a sack held open by a wire ring. Tests show that the accuracy of such sampling is sufficient for operating purposes. For instance, samplers were required to take duplicate samples at each face of four drifts during the progress of the work. One set of samples was called series A and the other series B.

Too much time would be lost if the miners had to wait while the sampler laid out and chiseled a neat groove across the vein; indeed, the varying degree of hardness of parts of the vein would make such procedure difficult. The same results are obtained by the use of the sampler’s pick. The sampler takes equal amounts of material from points along a predetermined line and catches it in a sack held open by a wire ring. Tests show that the accuracy of such sampling is sufficient for operating purposes. For instance, samplers were required to take duplicate samples at each face of four drifts during the progress of the work. One set of samples was called series A and the other series B.

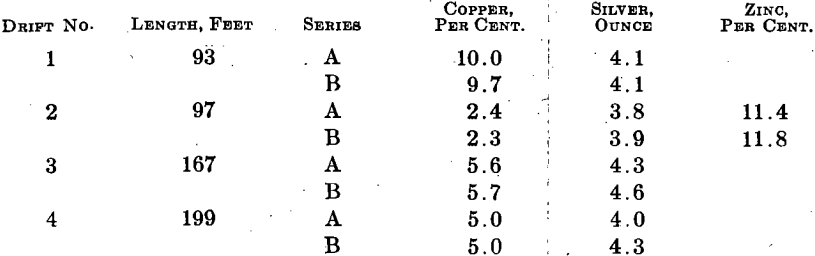

The drifts varied in length from 93 to 199 ft. Two sets of averages were prepared one, from series A and one from series B; the results are as follows:

Other tests are made from time to time and the chief sampler makes frequent trips underground, accompanying the mine sampler, and takes duplicates of the day’s samples. They do this independently, in fact without watching each other. A record is kept of these duplicates and each man’s results in his mine are tabulated for comparison with the results obtained by the chief. Assuming that the chief’s samples are correctly and accurately taken, the men are rated as high or low and are cautioned in the right direction. In order to be sure of the value of these tests, the assayer’s results are checked from time to time by carefully dividing a sample and sending parts to the four assay laboratories.

From time to time a meeting of the samplers is held and questions are asked. Occasionally, at these meetings, demonstrations are made to show how errors may creep in and to assist in the standardization of the methods.

REPORTS

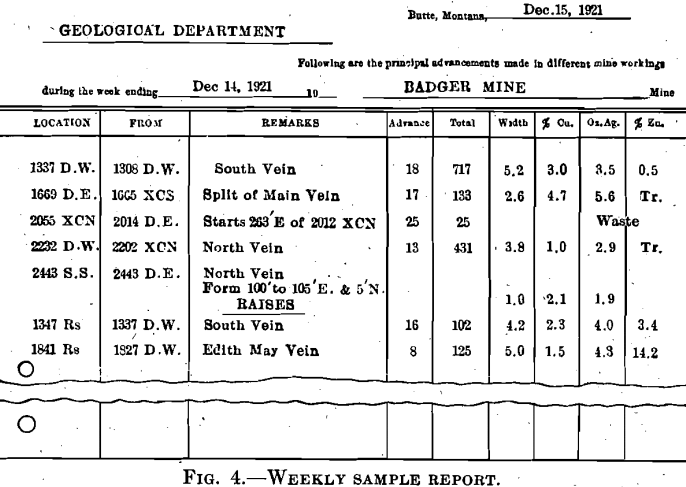

The samples taken are sent each day to the assay laboratory and the results returned to the sampler the next day. He keeps a record of the results in a book prepared for the purpose and makes a daily report to the Geological office. This report is a simple form, calling attention to new places started and giving the results of the day’s assays. These reports serve to check the calculation of the more formal weekly reports, which contain the average of the samples taken in each place for the week. The daily results are also copied into loose-leaf ledgers so that any averages required may be figured. They are then given the geologists who thereby keep in close touch with the progress of the development work. The weekly report ends with the samples taken and work done on Wednesday so that assay results are available; the averages are figured and the reports delivered to the general superintendent and the geological department on Friday. The method of figuring averages has been carefully standardized and the samplers are provided with type forms to show different cases. The weekly report gives the progress for the week, the total to date, and other relative data besides the average assay value. Fig. 3 shows a typical daily report and Fig. 4 a weekly form.

OFFICE RECORDS

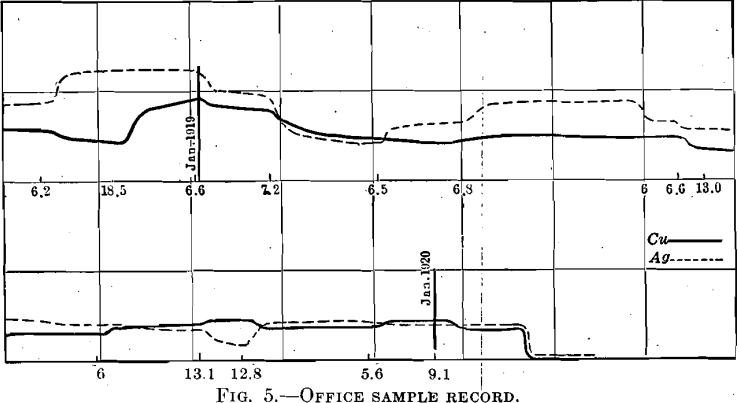

The principal office record consists of a set of cards cut from standard cross-section paper, ruled to tenths of an inch. Each drift and raise has a card and is identified by its number in the upper right-hand corner; the name of the mine is in the left-hand corner. The cards are kept in small boxes; they are arranged in alphabetical order for the mines and in numerical order for the cards in each mine. The horizontal scale on the cards is 1 in. = 50 ft., which is the same as the standard geologic map.

The vertical scale is 1 in. = 10 per cent, for copper, or 10 oz. for silver. A definite starting point is marked and a curve is plotted for each metal, using the weekly advance report to get the positions on the horizontal scale and the assay averages on the vertical. A black curve is used for copper and a red one for silver. The width of the sample is written under the base line in its proper place. These curves are useful in many ways. By placing one under the standard geologic map of the corresponding drift, it becomes an assay map. The curve shows the location of the better ore along the drift, it shows the proportion of silver to copper, and allows a fair estimate of the average assay value at a glance. If a curve descends precipitously to the zero line, the geologist visits the place to see if the vein has been faulted or if some change in the development work can be made. Curves for raises are plotted from vertical base lines and are equally useful. Fig. 5 shows a typical assay curve card. For special averages or other information and for estimates connected with ore reserves, the ledgers containing copies of the daily reports are used but the curves are satisfactory for most purposes.

For the estimating of ore reserves, there is a longitudinal section of each vein made to a scale of 1 in. = 100 ft. and projected on a vertical plane parallel to the strike of the vein. A certain minimum width and assay value is assigned by the operating department as the lower limit for ore. Then the drifts and raises on the long section are colored red wherever the assay curve shows the required grade of copper ore and green for zinc. Waste drifts and raises are colored gray. This color scheme shows quite plainly what should be included in the ore reserve for each section. Blocks are, therefore, laid out upon the section and their volume and tonnage calculated in the usual way. For the grade of these blocks properly weighted, averages are calculated either from the curve records or from the more complete daily reports in the ledgers.