The prospector’s most valuable prospecting equipment for his business is his knowledge of rocks and minerals; and the more thorough, complete, and practical is this knowledge, the better his preparation for the discovery of mineral deposits. Rearing this in mind, the foregoing descriptions of minerals and rocks have been accorded a rather more extended treatment than is usual in treatises on prospecting. Whenever the matter under discussion has had some special application to prospecting, the attention of the reader has been directed to this fact. In this manner, a great deal of the discussion of prospecting has been distributed throughout.

Earlier special information is to be found regarding each valuable mineral, as to its properties, the rocks with which it is associated, and the “signs” of its presence. For example, gold has been thus discussed; and, in addition, the use of panning in searching for gold, has been described. In Rocks and Rock Structures, there is occasional reference to those features of the rocky surface of the earth that are of special interest to prospectors.

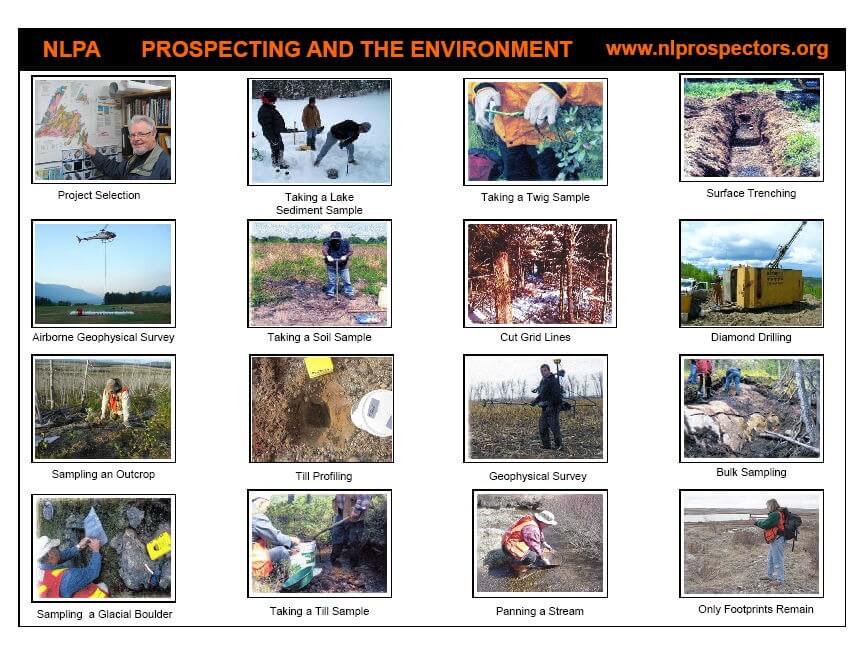

It now remains to discuss some details of the art of prospecting that are not covered in the preceding pages. Methods have changed radically in many regions since use of the airplane became general, and the prevalence of roads in what was largely unbroken forest even thirty years ago has displaced the canoe and the pack horse in the nearer reaches of the country. Similarly the fact that airplane photos of practically all parts of Canada, and accurate maps made from these photos, are now available has simplified prospecting and speeded it up. Another aid, probably of more use to the exploration companies than to the independent prospectors, is the maps showing anomalies located from the air by various geophysical methods. Still the actual discovery always involves the old foot-slogging method of prospecting to some extent, and in some cases it has been entirely responsible for recent important discoveries. In the following pages, therefore, the traditional Canadian method of prospecting will be discussed, as well as the ways in which it has been modified by recent aids.

Develop an Exploration Program

The size of the prospecting party, its composition, and the equipment required, are matters that vary so much with the nature of the country, the method of travel, the time to be spent in the field, and the special objects in view, that it is not possible to give any useful directions of general application. The method of search must be chosen to suit the conditions, which vary for different regions and minerals ; but there are a few general hints that may be usefully taken.

Systematizing the Prospecting Work

The work should be made systematic. While discoveries are sometimes made by men who wander around with little or no method, the most fruitful work is done by those prospectors who search in accordance with pre-arranged plans. Prospecting in a field where important discoveries have already been made should be begun by visiting some of these discoveries, to study the mineral deposits and the rocks in which they are found. There are often peculiarities in both minerals and rocks that are valuable “signs” for the guidance of the prospector.

How to Evaluate a Work of Geologists

The Government geologists have usually examined thoroughly the rocks, minerals, prospects, and mines of any field where important discoveries have been made; and they have prepared a geological map and a report giving most of the information about this special area that is likely to be of use to a prospector. In reports written during recent years, geologists have paid particular attention to the requirements and needs of the prospector; and these reports will usually inform him concerning the rocks that are likely to be barren of mineral wealth, those that are more likely to contain valuable deposits, and the particular association of rocks in which he is likely to make a discovery. In many cases, for instance, the deposits have been caused by large intrusions of granite; and the area most likely to contain veins is a strip of some other rock, along its contact with the granite.

Miners will Cooperate with Prospectors.—Those who have made discoveries, or have developed them into mines, are nearly always anxious to have more mines discovered and developed near them; the more mines there are in the camp the better the chances for good roads or a railway. On this account, as well as by reason of the spirit of good fellowship that marks miners and prospectors alike, the men in an established mining camp will usually take great pains to show a prospector over the ground they occupy, giving him the information they have that is likely to be most beneficial to him in his search of this field.

Prospectors should Travel in Pairs.—In general it is advisable that prospectors travel in pairs, whatever may be the size of the whole party. This is particularly desirable in Canada, where most of the ground to be prospected is covered with forest and is rough or mountainous, with many chances for getting lost, or for breaking a leg or arm, or being otherwise seriously injured. To avoid waste of effort by walking close together, it is well to follow approximately parallel paths, but remaining within hailing distance of each other. If the ground is well known to the prospector, or if the woods are full of men, as in the case of a “rush,” this precaution is, of course, unnecessary.

Outfit for a Pair.—When prospectors travel in pairs, it is advisable that each pair have an independent outfit, even in a large party. A tent 7½ by 10 feet, if of fairly light cotton or “silk”, is a good size for two men and their provisions; it should always be fitted with a sod-cloth around three sides and a loose cheese-cloth netting in front, to keep out mosquitoes, sand flies, and other winged pests, which would otherwise make life almost unbearable. It may here be noted that in most wooded areas of Canada, as well as the Arctic tundra, it is virtually a necessity during the fly reason to use a “fly repellant”, rubbed at intervals on the hands and face. Formerly oil of citronella mixed with olive oil was the stand-by; but in recent years certain synthetic oils and greases have been available that discourage the black flies, sand flies, and mosquitoes more effectively.

Some prospectors like to carry a heavy, waterproof tarpaulin or ground cloth, to sleep on and to use when traveling, to wrap around the blankets, tent, and the odds and ends, such as spare socks, and the indispensable “housewife,” which contains needles and thread, yarn, and tacks, for mending clothes, boots, and canoe. A water-proof box or can, holding a supply of matches should never be omitted from each prospector’s personal outfit.

Food Supply

The most important item of the outfit to any prospector, and one that often receives less attention than it deserves, is his food. Unless it is certain that the gun and fish line will furnish a part of the food (and it is seldom that this can be guaranteed) the prospector should carry food sufficient to last until the time he is certain he will get some more, either by going out for it, or brought to him by an airplane or other means. Formerly the prospector could take with him only desiccated foods (those that do not contain water), such as flour, sugar, rice, beans, bacon, oatmeal, dried apples, raisins, and desiccated (dried) potatoes. In some parts of Canada, accessible today only by pack horse, or on foot, this dried food is still the best to use.

It should be contained in a heavy, waterproof bag or pack sack, to protect it from the weather. In order to avoid breakage and waste of food, it is well to put each kind in a small cotton bag, tied at the mouth with a tape or string attached to the bag. These same little bags, by the way, often come in handy for holding samples of ore. If it comes to a pinch, such as when you are lost, or your pack horse dies, or your canoe is smashed, and you have to lighten your outfit, throw away your blankets, your tent, your ore samples, your pick, but do not throw away your food; if you do, you may throw away your life at the same time.

Quantity and Kind of Food

The quantity of food required has been established pretty well by experience. Allowing for an appetite somewhat beyond the ordinary, but not for waste (a good woodsman never wastes food), 3 pounds of dry foodstuffs per man per day is required, or roughly 100 pounds per man per month. If foods containing much water, such as potatoes (62% water), eggs (about two- thirds water), and fresh meat (about half water), are carried, due allowance must be made for this water in calculating the weight. The variety of food¬stuffs and proportion of each that should be carried in order to insure a wholesome diet, is so much dependent upon individual taste, that each must decide it for himself. The foods mentioned above will form the basis of the supply in any case. A number of practical precautions should be taken, such as having the butter in sealed tins and yeast in a moisture-proof package. These are learned best by experience. The following list will serve as a memorandum of the items required, and may be a guide as to comparative quantities. It totals 200 pounds, and will last two men from a month to six weeks.

Nowadays when prospectors are transported and supplied so commonly by airplane, the above bill-of- fare may be unnecessarily dry and monotonous in many cases. Fresh meat, vegetables, and fruit are now quite usual in a prospector’s camp, and many good prospectors today have their bread brought in, in place of baking it themselves.

Importance of Well-Cooked Food

Some prospectors think it does not matter much how their food is cooked, so long as they can get outside it; but they are wrong. Good cooking is one of the most important details of the prospector’s outfit. It used to be the habit among “old timers” to live on bacon, bannock, beans, and tea, the last being so strong as almost to float an egg; added to this, would be a little applesauce, as a luxury, and meat and fish when they could get them. These men would become actually ill from this half-cooked, monotonous diet, and they would have to come out to town every few months, usually for a spree, without eating, which physicked them, and gave their stomachs a new start when they went back. It is quite unnecessary for the modern prospector to waste time, money, and effort in this way; it is much better for him to do whatever is necessary to ensure wholesome meals, and thus keep himself fit during his whole season in the field. It is a comparatively simple matter to prepare good, sound, wholesome food, including the making of yeast bread, in the nest of small pails, frying pan, and reflector oven, which make up a complete cooking outfit, and which weigh but a few pounds. As this is not a cookery book, the subject must be left at this point, important though it may be.

The Prospector’s Tools

What should constitute the prospector’s tools depends entirely upon the stage of his work and the nature of the ground over which he is working. The old, accepted prospector’s pick, pointed at one end and with a hammer at the other, is a good tool, and it is better yet if it have a long handle fitted in an extra large eye. In this country, the rock is almost invariably covered to a large extent with a thin coating of moss; and to scratch this moss away, some prospector’s like to have instead of the hammer-pick, a light, long-handled mattock or grub-hoe, which has a pick on the other end; this is very effective for scraping off moss and light soil, and in cutting small roots. Another tool, not so common, but very effective, has a grub on one end and a hammer on the other, these two being used oftener than the pick.

The gold pan was at one time an indispensable part of the prospector’s outfit. It served not only to pan out gold and other heavy minerals from gravel or pulverized rock, but it was useful for mixing bread and for other chores around the camp. In recent years a small gold pan about 10 inches across has become more common than the original pan of the placer miner.

Recently the Geiger counter and the Scintillometer for testing radioactivity have become a common part of the prospector’s outfit, and may remain so for some years to come.

Landmarks for Camp.—Good drinking water is indispensable to the prospector; and in few, if any, parts of Canada where prospecting remains to be done is this difficult to obtain. The prospector sets up his tent beside the supply of water, whether it be lake, stream, or spring. If the camp be on a lake or stream, it will form a landmark, by which to find the camp when returning in the evening; a stream or a large lake is best for such a landmark. A small hill is most deceptive in appearance, as it is likely to look quite different when viewed from various angles. One must be very cautious when locating a camp, unless he has had considerable experience, in which case, it will have become second nature with him.

The “Canoe Prospector.”—It is the easiest thing in the world for the prospector to get accustomed to staying too close to his camp, either through fear of getting lost or through laziness. The “canoe prospector” of the lake country of Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba is a man who may become very expert at travelling and an adept at making a comfortable camp on the portage, but who seldom leaves the shore of the lake or the portage trail to conduct a real search for mineral deposits. It is a good thing to examine the shores and rock exposures along a portage; but it is likewise well to remember that all who have gone before him have examined these very places. The prospector that is most likely to make a “find” is the one who works forward systematically in unexplored territory, or in ground that has been traversed at wide intervals by the geologist, using every expedient that woodcraft and scientific study can suggest to him. A half-day’s steady walking through the woods in fairly level country will take him five or six miles from his camp; by returning by another and practically parallel route, a half mile or mile from the former, he can size up a block of land from two to six square miles in extent in a single day. This of course, gives him only a look at the rocks, such as a geologist would take.

But if he finds anything of particular interest, as a promising belt of rock, a contact zone, a mineralized outcrop, it may take him weeks to examine this area as closely as is warranted.

Prospecting Pocket Compass

When traveling through the woods, whether it be in a mountainous or a flat country, a good pocket compass is a necessity to every prospector; and learning how to use the compass surely and rapidly is one of the young prospector’s first duties. When the sun is visible, it is an excellent guide for direction, and it may be used instead of a compass. Its direction in the sky may be estimated by the time of day, bearing in mind the season of the year. It should be remembered that in midsummer in these northern latitudes, the sun rises in the northeast, approximately, and it sets in the northwest; at the equinoxes, in March and September, it rises in the east and sets in the west, and it is much lower in the sky during the day. Thus it is well to check up even the sun with the compass as the seasons progress, lest one forget its changes in direction. On a dull day, when the sun is obscured by clouds, the compass is indispensable, and it must be consulted frequently enough to determine landmarks by which to travel. In a country where hill tops or mountain peaks are visible, this is a comparatively simple matter; but when deep down in the woods of a valley or in a flat country, it is necessary frequently to check one’s course with the compass.

Judging Distances. — While it is a comparatively simple matter to determine the direction of travel, it is more difficult to judge the distance covered; hence, the young prospector should take advantage of every opportunity to perfect his judgment of distance. After years of practice, a prospector is able to judge how far he has traveled, and the direction, without giving much thought to the matter; that is, he has recorded in his subconscious mind the path he has taken, the distance traveled, and the direction, and he can make a good guess as to the distance to the camp and in what direction it lies. But the young prospector cannot do this; and he should travel at first with the aid of a map, on which distances can be scaled. It is a good plan, when on a lake, to estimate the distances from point to point, and note the times taken to cover these distances ; then check up the distances by scaling a map, or from information obtained from some reliable source. Calculate the speed of travel in both cases, and it will not be long before you will be able to judge quite accurately the speed of travel on still water. Four miles per hour in a loaded, two-man canoe is unusually fast paddling, as actual measurement will prove. The outboard motor or “kicker” gives, of course, considerably faster speeds. Once the actual speed of travel in a canoe has been determined, it will be a good gauge of distance over still water; and by allowing for the speed of the current, the distance along the stream can also be gauged.

Noting the times it takes to pass over a portage or trail of known length, will afford good means of measuring the speed of walking. When proper allowance is made for the slowing up where there is no trail, the speed across country can be judged roughly. In thick woods in level country, a mile an hour is good average speed, when off the trail; this allows a little time when scratching among the rocks. When traveling a mountainous country, with much climbing, the speed will, of course, be much less.

For accurate measurement of distance, counting paces is a valuable method, after having noted how many paces are required to cover a distance equal to the surveyor’s chain (66 feet), to 100 feet, to 100 yards, or to any measured distance, such as between the mile posts on a railway or across a measured portage. It is best to take your natural stride when counting, instead of three-feet steps, as is customary. Due allowance must also be made for the shorter steps that are taken when walking over rough ground or through thick woods, and for the crooked path that is followed in avoiding trees and other obstructions. Geologists commonly use this method of measuring distances; with practice, surprisingly accurate results are obtained.

Notebook and Diary

A notebook is required for systematic prospecting; and it is useful, though not essential, to keep in it a daily record, or diary. Sketches should be made of the ground examined; these should show streams and lakes, trails, survey lines, prominent hills, the kind of rock seen, and all special features, such as mineralization, faulting, shearing, or folding, together with such other facts as it may be desirable to remember. If claims are staked, all the particulars should be carefully recorded in the notebook; this will help the official mining recorder to place the claim on his map, and will be valuable evidence in case of a dispute concerning the ownership of the claim.

A Typical Day’s Work

Taking notes of a day’s journey and recording the observations made, is a simple matter when once understood; but it must be learned, like anything else. An example will now be given of a day’s work, the time being in July, with the observations and notes taken, and the manner of recording them.

Suppose the prospector is to travel several miles north from his camp, turn and go eastward for about a mile, then go south, and finally west to his camp. Assuming that he starts at about 8 o’clock, the sun, if visible, will be seen directly on his right, when he faces north. If the sky is overcast, he must use his compass. He marks a point at the bottom of the page in his notebook to indicate the position of his camp; and since he intends to move toward the east later, he puts this point near the lower left-hand corner (See Fig. 136). It is always assumed that the bottom of the page is south and the top is north, a vertical line being always a north and south line. The notebook should be ruled with faint blue or red lines, as indicated in Fig. 136 ; the distance between these lines may be used to measure distances. In the present case, this distance (interval) is assumed to be 440 yards = ¼ mile, as noted on the sketch. Near the camp, some granite rock is exposed, which is indicated by some small X’s, and the notation (granite).

After a ½-hour’s easy walking to the north, he crosses a portage trail, which he makes note of as being ¾ mile from camp, the distance it is judged to be, or 3 intervals from his camp point on the sketch. He follows this trail, in a general north-westerly direction, and finds more granite rock, which he also marks. After walking about 300 yards (ascertained by pacing), he comes to a small lake or pond, which he sketches in. He estimates its length as ½ mile, east and west, and its width as 1/8 mile, and notes a prominent pine-covered cliff on its north side. Passing round the edge of the lake he finds that this cliff is the end of a ridge of diabase rock, and he follows it northward for ¼ mile, marking it in the book with a series of little v’s. The rock on either side is found to be granite (indicated on the sketch by little X’s), and the diabase is in the form of a dike, 300 feet wide; it terminates at the north end in a swamp, through which progress is difficult and very slow. The width of the swamp is noted, and the swamp is marked down in the notebook, being indicated by a conventional sign that represents a tuft of marsh grass. From the open space on the north side of the swamp, he sees towards the northeast, a hill top and a cliff, which he proceeds to investigate. On reaching it, he finds it to be greenstone—a convenient name for a number of fine-grained, greenish rocks, whose real nature it is impossible to determine in the field. This is the rock that the geologists have indicated as favorable to the occurrence of mineral deposits in this locality. He therefore examines this rock outcrop very carefully; and before he realizes it, it is noon. By this time, the sun is high in the heavens, and is practically in the south. At this time of the day, however, the sun changes its direction so rapidly that the compass is the only reliable guide.

After eating his lunch by a tiny stream in a gully, the fire, over which he has boiled some water for his tea, is put out very carefully, and the search is resumed by walking over the bare outcrop and scratching down at intervals the moss that covers the rock. Presently, he finds an outcrop that is composed half of schisted greenstone and half of rusty-looking material. He ascertains that this gossan runs under the moss; so he strips off the moss, and the gossan is found to be a band, 20 feet wide, running east and west, with the strike of the schist, for a distance of at least 40 feet. When picked into, it is found to contain specks of blue and green color, which suggests the copper minerals; and it is covered at both ends with boulder clay. Following eastward, in the direction of this band, or vein, the rusty-material outcropping is again found at the foot of a sloping outcrop of schisted greenstone.

The sun is now getting low, giving warning that the prospector has spent more time than he thought on this interesting outcrop. So at intervals across the outcrop, he digs up with his pick some of the rusty material, puts it in a handkerchief, and mixes it thoroughly; he then divides it roughly into quarters, throwing away two diagonally opposite quarters, to reduce it to two or three pounds in weight. The remainder he ties up securely in the handkerchief, to grind up and pan when he gets back to camp, in order to see if it contains any gold or other heavy minerals. Since he knows he will want to return to this spot, he blazes a prominent tree on the cliff he first saw (see Fig. 136), and then blazes a line eastward for a hundred yards, so that he can crosscut and pick it up again. He finds a stream, 8 feet wide, flowing northward across this line, so he records this on his sketch; he also notes that there appears to be a large lake, about ½ mile to the north; this he also records, using a dotted line to show that he is not certain of this. (In fact, whenever he records something he is not sure of, he uses a dotted line; note the dotted line between the portage he first crossed and the one he crosses on his return trip. He assumes that they are both the same portage, connecting the small lake with Otter Lake).

The notebook now comes in handy. If he has recorded properly, and to scale, the distances traveled, and the directions are accurate, he can readily determine the direction and distance to his camp. His sketch map shows that the camp is almost directly south, and flat it is about 2¼ miles away. Therefore, he strikes south, (the sun now directly on his right again, in the west) and again crosses a stream, flowing to the east. He suspects that it is the same stream that crosses his blazed line, and that it drains the big swamp he crossed in the morning. On the way south, ¼ mile away, he strikes outcrops of granite gneiss, and then spies a large lake in front, at the end of which, he finds a portage trail, which he is almost certain is the one he crossed in the morning. He knows pretty well where he is now; so he continues southward, and soon comes to his own lake, which he recognizes because of the pine-covered island in front of his camp, ½ mile westward along the shore. The prospector’s work of exploration and prospecting for the day is now finished.

Using the Pocket Compass

The following brief description will be found of value to those who have never traveled with the aid of a pocket compass:

When the compass is so held that the needle is level and turns (swings) freely in a horizontal plane, the needle will always point to the north magnetic pole. The end that points north is usually blued, or else it is marked with a letter N, or it has a little cross bar. Under the needle is a card, marked to indicate the various points of the compass, and also in degrees. The magnetic north is seldom in line with the true north, and the deviation between the true north and the magnetic north is called the magnetic variation or declination which varies from place to place. The magnetic variation is marked on the maps for the particular map area in which the prospector is located, usually east when prospecting in Canada. This variation must always be taken into account when determining true directions by means of a compass, as when staking a claim.

Suppose it is desired to go due north, and the map states that the magnetic declination for that locality is 15° east. Hold the compass steady, so the needle swings freely in a horizontal plane; then turn the compass (still keeping the needle horizontal) until the needle falls over the 15° mark to the right (east) of the point marked N; this point N is now due north. Look in this direction and see if there is any landmark in line with it. Assuming that the point N is in line with a large, dead pine tree, about 200 yards away, walk to this tree. On arriving there use the compass again, in the same manner as before, and locate another landmark directly from this tree, which may be a bare peak of rock in the distance; on arriving there, another landmark is located as before. It is evident that in a densely wooded country, the landmarks must be determined more frequently than in a more open country.

Suppose the prospector having gone north as far as he wishes now desires to go east. He sets the compass with the N point of the card pointing due north, as before; keeping the compass steady, preferably resting it on some convenient stationary object, he sights (looks) along the line passing through the points marked W and E, and picks up a landmark beyond E, toward which he goes, and then repeats the operation. If he wishes to go southeast, he sets the compass so the N point indicates true north; then he sights along a line passing through N W and S E, and picks up a landmark beyond the S E point. In similar manner, any desired direction can be found and followed. It is necessary, of course, to estímate as closely as possible, all distances traveled in any particular direction, and both directions and distances should be taken and recorded in the note book; and these should be verified whenever there is reason to suspect a mistake has been made, or when it is necessary to go around an obstruction and the landmark selected is difficult to locate.

Prospector’s License, Staking, and Recording

The mining laws regulate prospecting as well as mining, as might be inferred from the mention of the mining recorder. These laws vary in the different provinces, and the details must be learned for each; but, in general, they agree on certain main points. For instance, a prospector must take out a license (by payment of a few dollars), to give him the legal ownership of what he finds. He must then stake his claim in accordance with certain regulations, which are designed for his own protection. He must make a record of his staking at a Government office, again for his own protection, and also to let those in charge of the public lands know what part of these lands has been claimed as private property by right of discovery. Afterwards, it will be necessary to perform a stated amount of work on each claim, in order that he may retain its ownership. The prospector will gather information concerning these points as he pursues his calling and mixes with his fellow prospectors.

Geological Survey Reports and Maps

Prospecting is gradually becoming systematized through the use of geological surveys, by means of which the country is mapped in such a way as to indícate the areas where valuable minerals are likely to be found. The prospector’s initial discovery may call attention to some particular area, which the geologists then survey, map, and perhaps extend. Cooperation between the geologist and the prospector is becoming more and more hearty and productive.

Geological reports and maps may be obtained from the Geological Survey, Ottawa, and from the various provincial surveys. Those who are preparing to prospect in Canada are advised to write first to The Chief, Division of Geological Information, Geological Survey, Ottawa, stating where the proposed prospecting is to be done, and asking for maps, reports, and other information. The purpose for which the maps are to be used should also be specified.

What the Maps Show

Geological maps show the rock formations, and also such features of the country as streams, swamps, hills, sand plains, etc. Topographical maps do not show the geology of the country, but they show streams, lakes, etc., and in addition by means of so-called contour lines, the variations in elevations above sea-level.

If a great deal of country is to be gone over, a small-scale map, is best; but if a relatively small area is to be carefully prospected, a large-scale map is advisable.

A special series of maps, issued mainly by the Geological Survey, Ottawa, shows the magnetic contours obtained by airplane surveys with a magnetometer. These maps show the magnetic disturbances or anomalies caused by the magnetic minerals, magnetite and pyrrhotite. When there is enough of these minerals in the rock, the magnetic anomaly is marked plainly on the aeromagnetic map, and has been very useful in locating both payable deposits of magnetite and mineralized geological contacts where magnetite is relatively abundant.

Another system of surveying from the air called the electromagnetic system, recently inventsd by Canadian geophysicists, measures the electrical conductivity of the rocks, which increases markedly where they contain a large proportion of sulphides. This method has been responsible for the discovery of some large deposits of sulphides containing copper, lead, and zinc, completely covered from view, and promises to help in finding many others. No government agency has yet (1955) commenced to make and distribute these maps.

Map Reading

Aside from those who make maps or who have used them consistently, few realize what a vast amount of information can be placed on a single sheet. This result is accomplished by the use of conventional signs and symbols, whose meaning must be well understood before a map can be fully utilized. The prospector should learn how to interpret a map drawn to scale; the use and meaning of the conventional signs for rivers, lakes, hills, roads, railways, etc.; and all other information that the map conveys to one who can read it properly. In addition to the foregoing, geological maps have signs to indicate a portage, rapids and falls, the different kinds of rocks, veins, shafts, and other features of interest to the prospector ; all these are explained in the Legend, which is placed on one side of the map. Usually, the different kinds of rock are marked on the map by use of various colors. Sometimes, on the smaller maps, signs are used for this purpose, much like those shown on the sample sheet from a notebook, Fig. 136.

Sample Map. — A sample map showing a small part of gold-mining camp is illustrated by Fig. 137. In the lower left-hand corner is a Scale of Feet, by the aid of which distances may be measured on the map. The part of the scale to the left of 0, between 0 and 500, is subdivided into 5 equal parts; hence, each of these small intervals represents 500 ÷ 5 = 100 feet, while the long intervals represent 500 feet. By means of this scale, it is ascertained that the area represented by the map (area plotted) is 4000 feet long and 2300 feet wide. As there is no arrow or other mark to indicate north, it is assumed that the end boundary lines run north and south, and that the upper edge of the map is the north boundary.

The legend gives the key to the conventional signs used on this map. Two classes of rock are shown; and since the Timiskamian sediments are the lower of the two kinds mentioned in the legend, these rocks are at once known to be the older. When more than one kind of rock is indicated in a legend, the oldest is put at the bottom, the next older just above this, and so on, the youngest being at the top. The map itself shows a quartz diabase dike, an olivine diabase dike, and a number of dikes of feldspar porphyry and syenite porphyry.

Contour Lines

It will be noticed that the map is covered with a large number of irregularly curved lines; these are the contour lines, and each

such line has a number marked on it. Assuming that every contour line represented a path, and that one were to walk along one of these paths, he would be always at the same elevation above sea level, so long as he did not step out of the path. According to the legend, the contour interval is 10 feet; this means that the difference of level between any two consecutive contour lines is 10 feet. Evidently, then, when the lines are close together, as in the lower right-hand, or southeast, corner, the slope must be quite steep. Thus, if one starts from the line marked 1120 and goes north until he reaches line 1070 he will descend 1120—1070 = 50 feet while walking a horizontal distance of about 270 feet. This will land him on a small plain, as indicated by the absence of any contour lines. Consequently, the farther apart the contour lines the more level the country; and the closer together they are the more hilly it is. Again, referring to the map, note that the ground between the words “Main Ore” and “Teck,” which has a length of about 900 feet and a width of about 350 feet (as measured with the scale of feet), contains no contour lines; but on the north side, it is bounded by the 1070 contour line and on the south side by the 1080 contour line. From this it is known that this piece of ground is almost level, with a gentle rise to the south of 10 feet in a distance of 350 feet. Toward the east, at the word “Ore,” the contours come close together; here the 10-foot rise takes place in a shorter horizontal distance, and the slope is steeper.

Sections

This little map was made to show a part of the main ore zone of Kirkland Lake. Below the map, and to the right of the “legend,” is a section taken along the line HJ of the Main Ore Zone, and following the dip. This section shows how the ground would look if a thin vertical slice were taken to a depth of 300 feet above sea level (the depth is shown by the scale on the left of the section and also by the note, “above sea level,” at bottom of scale in sectional view). The scale indicates that at H the elevation is about 1125 feet, and that it is about 1040 feet at J; note that these heights agree with the elevations indicated by the contour lines near these points. At the left of the map is another section, which has been taken along the line KL, very nearly at right angles to the other section. This section shows the angle that the dip of the Main Ore Zone makes with the horizontal. As will be noted, the dip is nearly vertical or 90°. Referring to the longitudinal section, a note thereon states, “the longitudinal section dips 80° south;” this means that the thin slice forming the section is not situated perfectly vertical, but slopes toward the south. The other section (cross section) is vertical, which fact is indicated by the wording. “Vertical Section K-L,” which means a vertical section taken in the direction of the line KL.

Irregularities in Staking Claims

When a claim is laid out by locating the directions of the bounding lines with a compass, and determining their lengths by pacing off the desired distances, the results obtained may differ considerably from the true lengths and directions, as is well exemplified by the two claims here shown, Fig. 137. The prospectors who staked them intended that both these claims, the Kirkland Lake and the Orr, should be square claims, 1320 feet (one-quarter mile) on each side. The east and west sides were intended to run true north and south, and the north and south sides were intended to run true east and west; but a glance at the map will show how far they came from attaining their object.