Table of Contents

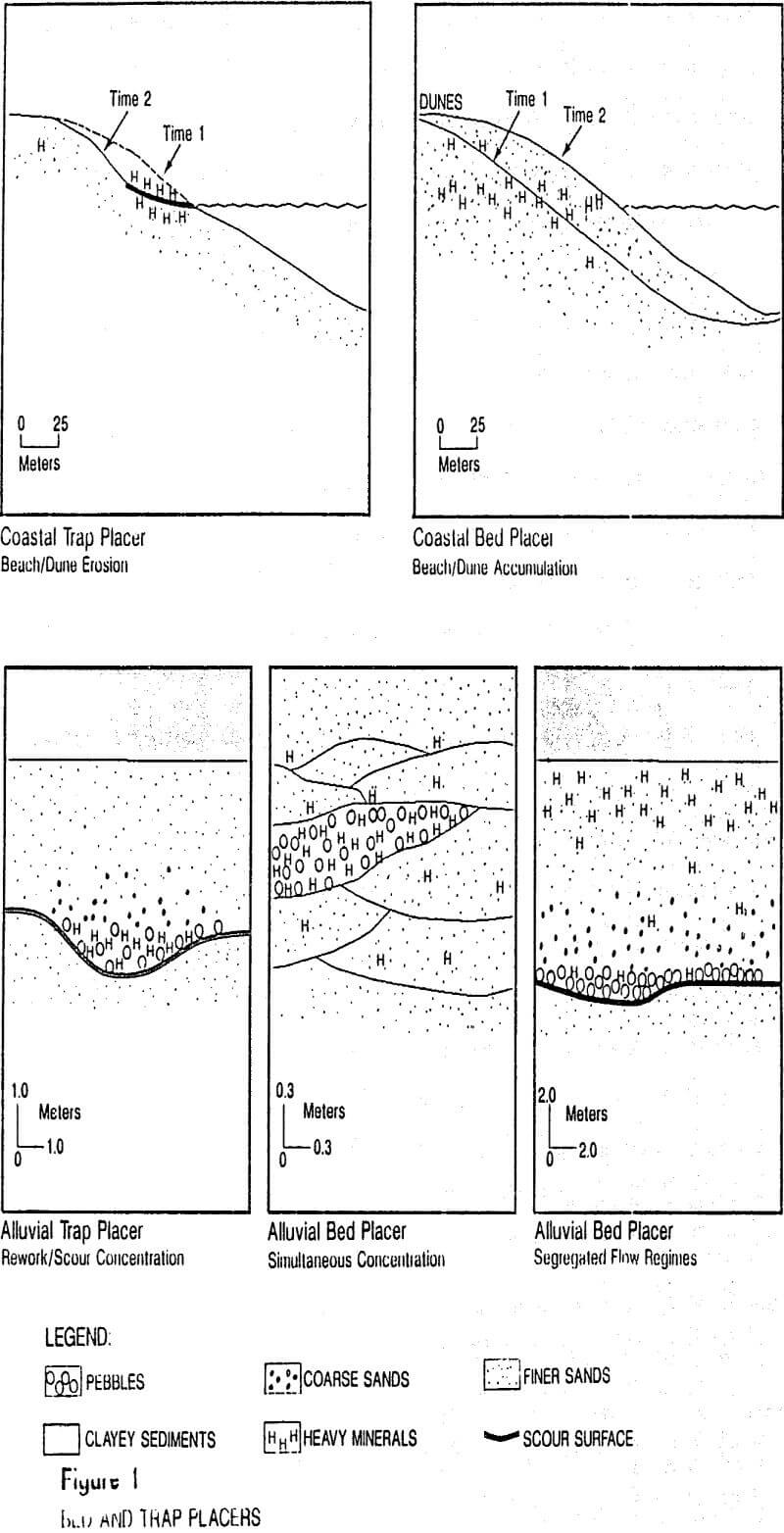

Concentrations of minerals between 3.5 and 5 specific gravity such as ilmenite, rutile and zircon in large accumulations of sand constitute “heavy mineral” placers. Two fundamentally different modes of formation characterize “trap” and “bed” placer variants. Smaller and generally higher grade trap placers form during sediment erosion or reworking. Because of their smaller size, they rarely yield economic heavy mineral deposits.

Trap and Bed Placers

Fundamentally, a trap placer is one where the higher specific gravity grains have become caught in a manner similar to gold in a riffle box. Once deposited, the grains of greater specific gravity fail to become entrained and to move away with subsequent fluid flows as do the other grains. A critical point to make here is that erosion and failure to entrain occur sometime after the grains first were deposited. Trap placers, unlike the sluice box, are characterized by later reworking of the original sediment and passive collection of grains that are essentially not displaced by the later fluid flow.

Trap placers quite often exhibit high grades. They also often exhibit wide particle size discrepancies between the matrix and the heavy minerals. Great care should be taken when identifying by using such internal evidence, however, a shoreline trap placer will have only a sand composition if sand was the only source material. The same figure also shows a heavy mineral-rich pebble bed where the two grain types appear to have gathered together simultaneously and not in a two step process. It is field evidence of erosion and reworking that best indicates a trap placer. Unconformity, erosion, and scour surfaces at outcrop scale characterize all trap placers.

A bed placer is one where higher specific gravity minerals accumulate in direct response to the fluid and grain flow regime operating at or close to the time of their deposition. All of the minerals, whatever their size, shape or specific gravity, have been deposited or “bedded” together in response to the conditions operating at a particular time. No erosional breaks link the high heavy mineral zones.

Bed Placer Examples

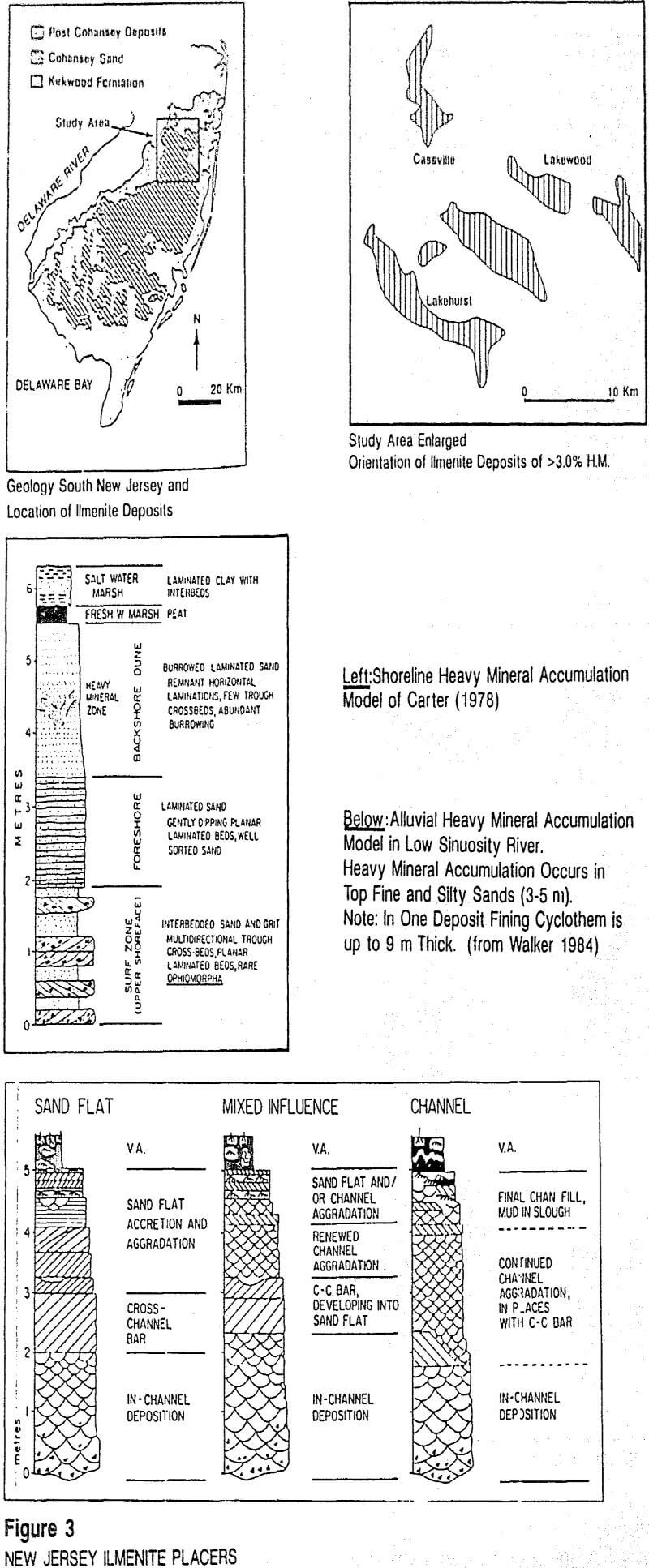

The question of environment, however, has not been settled. Logging and study of over 100 holes, indicate that the heavy mineral placers are river deposits from the former Millstone, Delaware and even Schykill rivers that owe their preservation to these rivers’ capture and deflection southward.

Evidence includes:

- Numerous drill holes show the Kirkwood-Cohansey Formation contact to be an unconformity whose topography includes valleys up to 1.5 km wide and over 5 m deep.

- The fining upward sequences of Carter are in fact multiple (three to four in some holes), stacked on top of each other with top portions of most missing due to erosion and scour .

- The orientation of known deposits runs almost perpendicular to the most likely shoreline trends (Figure 3).

- The deposition from marine or brackish water evidenced from fossils can be explained as marine incursions into valley environments similar to those of Tidewater, Virginia and North Carolina today.

Whatever the environment of deposition, shoreline or river, the basal Cohansey exhibits a very clear indication of the effectiveness of a hydrodynamic flow regime in segregating clastic material not only according to specific gravity but also to size.

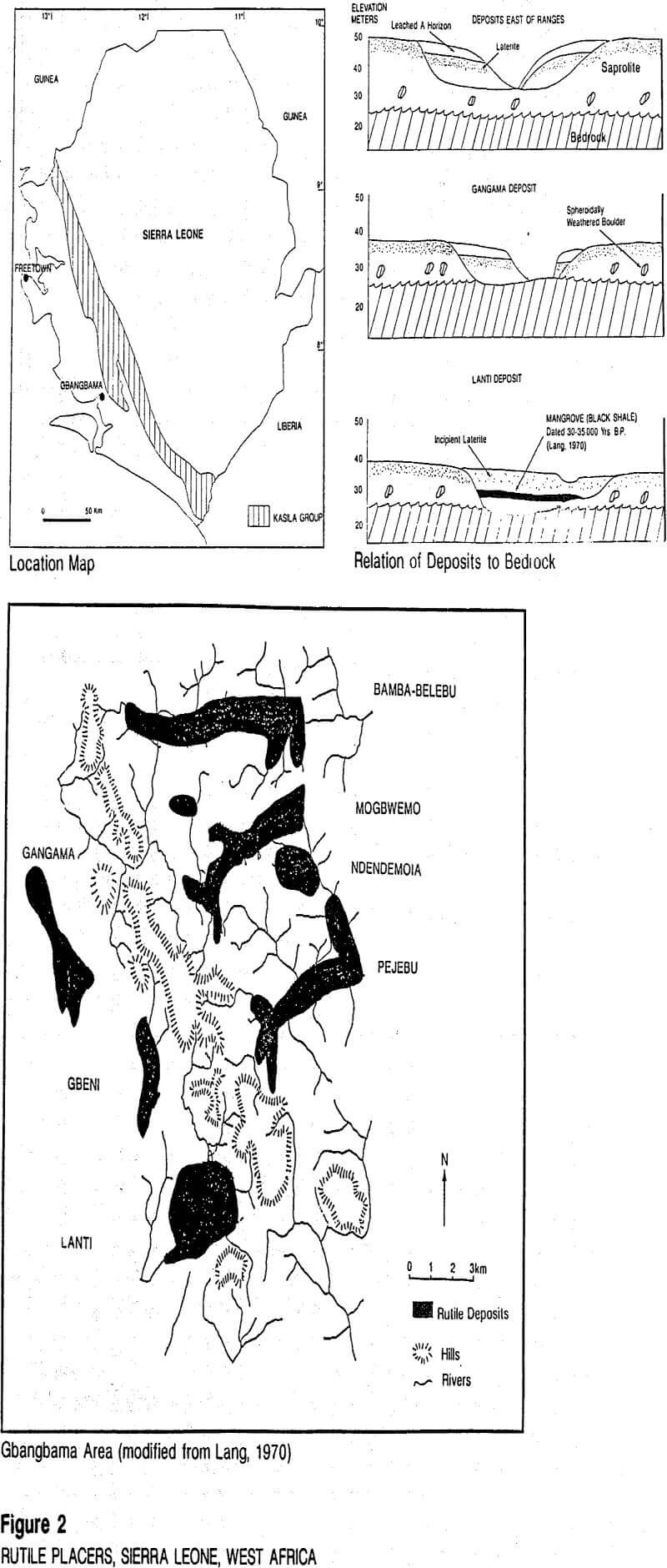

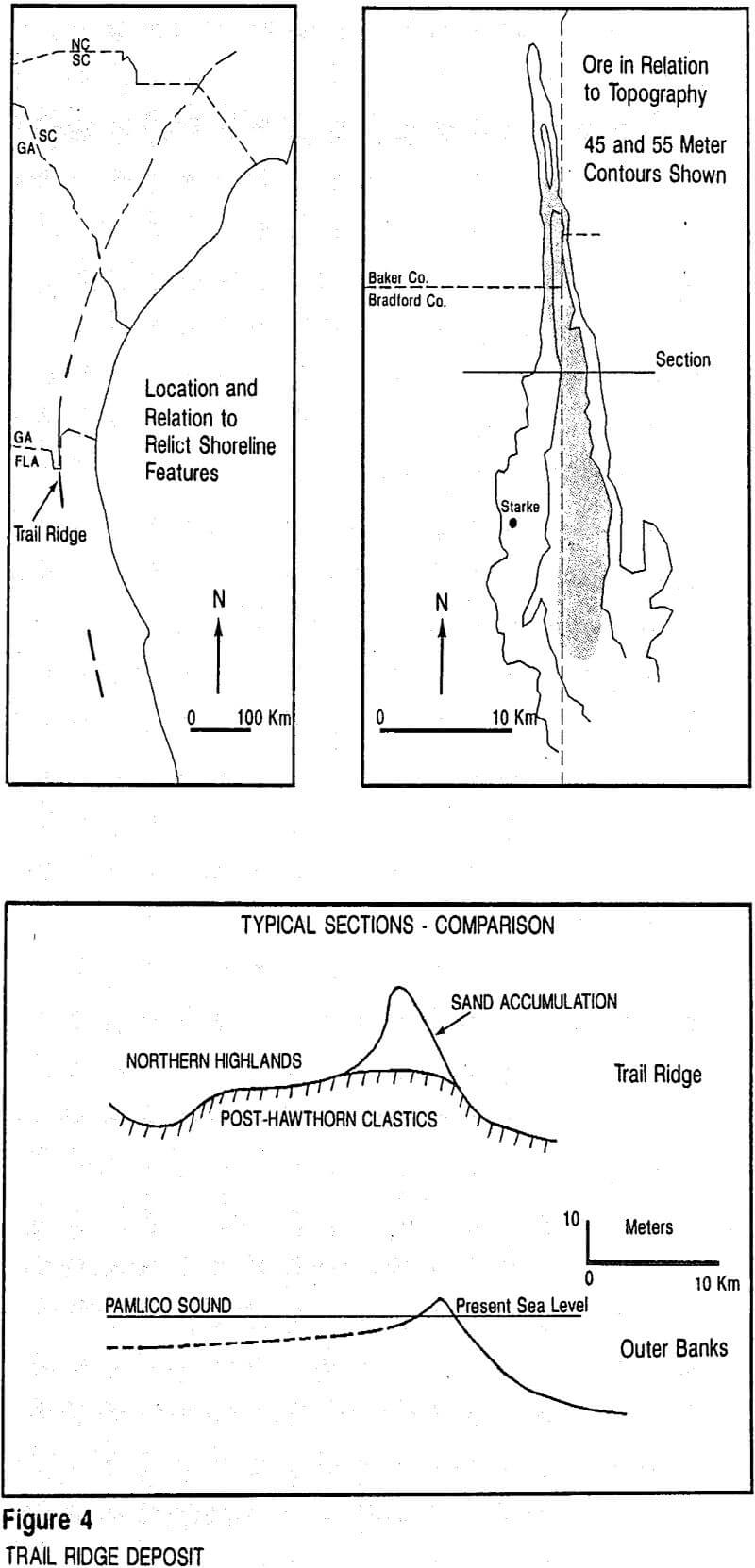

The Trail Ridge deposit of Florida is a well known heavy mineral placer developed near the south end of a shoreline that extends northward to Georgia, the Carolinas, and probably even into Virginia, where recently new discoveries have been announced.

Source rock terrain likely lies 300 km away in north and central Georgia. From this area in the late Tertiary fluvial, deltaic and marine “Post Hawthorn” clastics accumulated in north Florida. Since that time, uplift in Florida on the Peninsula and Ocala Arches has resulted in the deflection of the ancestral drainage to the north and west (the Altamaha and Flint rivers respectively). The marine transgression in the southeast that gave rise to the Trail Ridge deposit eroded and remobilized the post-Hawthorn clastics which became source material for the deposit.

Placer Exploration

In general, placer exploration should proceed by:

- Locating an area with the mineral wanted. This can be done using standard techniques of geochemistry, geology, and even by panning and hand-drilling.

- Deciding if commodity price and mining costs require high grade, small size erosive trap placers or their lower grade, larger size bed placer counterparts.

- Looking for trap placers either by prospecting feature-wide unconformities on large scale units such as alluvial fans and deltas, or searching for rework levels and scour surfaces in valley fill, terraces, and other smaller geological units.

- Looking for bed placers in situations where fluid flow regimes with minerals sorted according to size, shape, and specific gravity have left thick or widespread sediments. Large size could be due to lateral, longitudinal, or vertical migration, or, to preservation by removal and storage of concentrations repeatedly created in time.