Table of Contents

In ground sluicing the gravel is excavated by running water not under pressure. Booming is a variation of ground sluicing in which water is stored in reservoirs and is intermittently discharged in large volumes over short periods to obtain the maximum erosional and transporting effect on the gravel. The most favorable conditions for ground sluicing usually occur on the benches and upper reaches of creeks where pipelines, flumes, or ditches, which add greatly to installation costs, are not required. The method is not efficient if the gravel is cemented and, although applicable to gravel containing boulders, considerable additional work is required for handling. Ground sluicing and booming often have been employed to remove barren or very low-grade, light material covering the pay gravels during high-water seasons in conjunction with other methods for mining the gravel.

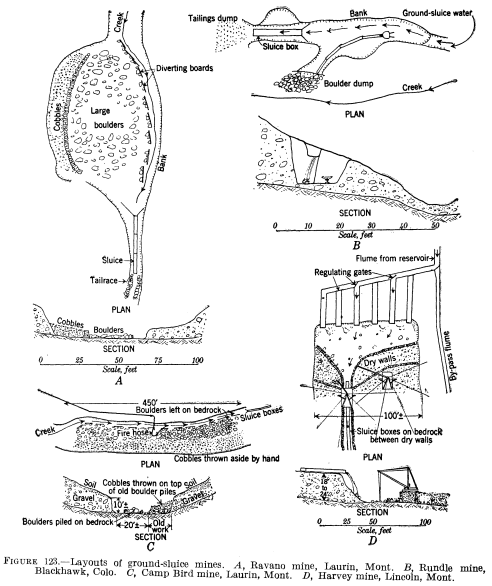

Excavation by running water may be accomplished in two ways, depending upon surface and bedrock topography and gradients and thickness of the deposit—(1) by diverting the stream to undercut the bank and carry away the caving gravel and (2) by running it over the upper face or crest of the bank, the gravel being broken by the cascading effect. Figure 123 shows four typical ground-sluicing operations. At A and C are shown adaptations of the first method and at B and D of the second method. In C is shown a pipe line carrying water under a 60-foot head and terminating in a fire hose and nozzle employed to remove the top soil and to assist in undercutting the bank. Booming was employed in the operation shown at D, where the gravel bed was 18 to 24 feet deep and 90 feet wide. The bottom 6 feet was fairly tight and by overcasting the water it scoured away this stratum.

The water-borne material is deflected to sluice boxes, in which the gold and heavy minerals collect behind or between the riffles and are later cleaned up in the usual manner by first running clear water through the sluice until it is free from gravel and then removing the riffles section by section, beginning at the upper end, while a light stream of water is passed through. Boulders not transported by the waters must be moved aside to permit cleaning the bedrock beneath them and considerable labor may be required for this purpose. At D, figure 123, is shown a derrick for handling large boulders; at other places they are blasted or removed by hand or by cableways or other mechanical means.

In ground sluicing and, indeed, in all placer work the bedrock must be cleaned carefully to recover gold that naturally tends to collect in cracks and other irregularities of its surface.

Table 45 is abstracted from data given in Information Circular 6786 on a number of ground-sluicing and booming operations. Wide variations in costs are shown, and it may be noted that whereas it was stated previously that for shoveling into boxes (water used only for washing the gravel) about 1.3 to 3 cubic yards of gravel could be handled per 24 hours with a flow of 1 cubic foot of water per minute (1.95 to 4.5 cubic yards per miner’s inch per day), when water was used for ground sluicing and booming the duty per miner’s inch per day at the tabulated mines ranged from 0.04 to 1.7 cubic yards. From these data it appears that ground sluicing and booming usually may require roughly 5 to 10 times as much water as shoveling in.

The mines described are the larger ones and a few typical small ones visited by the authors in 1932. Comparable data concerning them were shown in table 7.

Morgan

Richard Leoncavallo was working a pit on the Morgan placer on Clear Creek below Blackhawk, Colo., in July 1932. The gravel was tight, coated with clay, and overlain by 2 or 3 feet of recent wash and mill tailings. Cuts about 6 feet wide radiated from the head of the sluice boxes, following rich streaks on a false clay bedrock. All the gravel had to be loosened by picking, which was done while the water was running over the face of the cut. Boulders more than 6 inches in diameter were thrown out by hand. Some of the gravel near the head of the sluice was shoveled in by hand.

About 70 miner’s inches of water was used; some of the sediment in the creek water was settled out in a small reservoir above the mine. The sluice consisted of two 10-foot boxes 18 inches wide and 12 inches deep having a grade of 12 inches per box. The first 4 feet was floored with 1-inch screen placed tight on the bottom of the box. Below this ½-inch screen was laid over carpet and canvas. A canvas apron was placed in the pit just ahead of and a few inches below the level of the sluice; most of the gold was caught on this canvas. The clay bedrock was cleaned by shoveling the top layer into an 8-inch box built and set up for the purpose.

An average of 2¾ yards was washed per day with one man working. At $3.50 per day the labor cost would have been $1.27 per cubic yard. The total operating cost, allowing $0.02 for supplies, would have been $1.29 per yard.

A number of men were conducting similar operations farther down Clear Cree; none were making wages.

Ravano

About 775 cubic yards of gravel was sluiced by Tony Ravano in 3 months, including 12 days for cleaning up bedrock, on Harris Creek near Laurin, Sheridan County, Mont. The average run-off in the creek during the season was about 30 miner’s inches. This water was stored overnight in a small reservoir, the gate of which was partly opened in the morning, allowing a stream of about 150 miner’s inches to run until noon. Only the natural flow ran during the afternoon. As the flush water reached the pit it was deflected by boards and rock dry walls against the bank on one hide of the pit and thence through a sluice. (See fig. 9 A.) The action of the water was assisted by picking into the bank. During the afternoon boulders over 6 inches in diameter were rolled back onto the bedrock previously exposed. Stones 3 to 6 inches in diameter that were not carried out by the water were thrown clear of the pit by hand. All fine material was washed through three 12-foot boxes with longitudinal pole riffles, but nearly all of the gold stayed on the bedrock. Other miners working on the same creek by this method did not use any boxes except for cleaning up they considered that a good extraction of the gold was made in this manner.

In clearing up bedrock the sluice was extended into the pit one box at a time, The boulders were removed from the bedrock, which was then loosened by picking, and the material was shoveled into the box. As each box was placed the boulders from the next section above were moved back on the part cleaned up where they formed a bed about 2 feet deep. All of the material that was piled on bedrock had been handled twice. A total of 84 shifts was worked, and an average of 9 cubic yards was moved each day. At $3.50 per shift the labor cost would have been 40 cents per cubic yard. There were no expenses other than labor as old timber was salvaged for the sluice boxes.

Bar No. 1

In July 1932, Bar No. 1 placer on Kamloops Creek near Granite, Colo,, was being mined by three men working on one shift per day. About 60 miner’s inches of water was used, which came from a ditch at the head of the area being worked. Three 12~foot boxes 12 inches wide and 8 inches high, with a grade of 18 inches to the box, were used for a sluice.

The ground washed was 6 feet deep, comprising a flat bar on a false clay bedrock. There were very few boulders. Conditions were favorable for ground-sluicing. The men, however, were inexperienced and did not work to the best advantage. The water was spread out over too much ground and irregular cuts were taken, leaving small tracts that could be moved only by hand. The boulders were handled 2 or 3 times before final disposal. Gold was lost, as not over one half of the bedrock area was cleaned up.

About 9 cubic yards was handled daily. With wages at $3,50 per day the labor cost would have been $1.17 per cubic yard. Allowing 2 cents for supplies the total cost would have been $1.19.

The adjoining ground was being worked by an experienced man who moved nearly four times as much ground per man-shift with the same amount of water and extracted a larger proportion of the gold in the gravel.

Osborne

In July 1932, W. H. Osborne with three other men was running a ground-sluice cut in a gravel bench on California Gulch of Cedar Creek near Superior, Mont. This cut was to reach bedrock and was then 120 feet long and averaged 20 feet wide and 15 feet deep. The water cascaded down the face of the cut. Two men loosened the gravel with picks and rolled boulders out of the way. One man worked on the flume and one built boxes and assisted elsewhere when needed. Two men worked on night shift. Small boulders were piled beside the sluice. The ground contained some large boulders which were removed from the cut every other day by a steam derrick working half a shift. Those up to 3 tons in weight could be hoisted with the derrick. Larger ones were drilled with a jackhammer, using steam from the derrick boiler, and blasted.

The water supply was insufficient for good work. On July 8 about 80 miner’s inches was available. The boxes had been 24 inches wide, but as the water decreased the width was narrowed to 13 inches. The grade of 4 inches per 12-foot box was too flat for the coarse material being mined; the boxes clogged if not attended continually. Table 7 shows that 9 cubic yards was being washed per man-shift. At $3.50 per shift the labor cost would have been 39 cents, per cubic yard. Supplies cost about 3 cents, making a total of 42 cents.

Rundle

W. B. Rundle. was ground-sluicing at Blackhawk, Colo., in July 1932. Part of the water used was from a pressure pipe. The material being washed consisted of 2 or 3 feet of tight creek-bed gravel overlain with 5 or 6 feet of recent wash and mill tailings. A cut was started at the rim of the creek bed and extended upstream; the face had just reached bed-rock. The layout of the workings is shown in figure 9 B. The ground was partly loosened, and the boulders were washed clean by water from a 2-inch nozzle under a head of 27 feet. Some picking was necessary to loosen the virgin gravel. The overburden and the loosened material were washed into the boxes by the ground-sluice water which poured over the end of the pit.

All material over 3 inches in size was forked out into a wheelbarrow and taken to a rock dump. The ground sloped steeply upward on the hill side of the pit, and the oversize had been forked out of the pit on the creek side until the rock pile reached such a height that it was easier to use a wheelbarrow.

The riffles consisted of wooden cleats placed 5 inches apart and were of ¾-inch square material with the downstream edge beveled backward. The bottom of the box was lined with Corduroy cloth with the corrugations at right angles to the box; wire screen was placed over the corduroy. The water contained flotation tailings, including a large quantity of pyrite from a concentrator up the creek. The sulphide, however, did not clog the riffles in the sluice box.

An average of 3 cubic yards was washed per day, At $3.50 per shift the labor cost would have been $1.17 per cubic yard; the total cost, with 2 cents per cubic yard for supplies, would have been $1.19.

Bar No. 2

In July 1932, Jim Wiley, with one helper, was mining a flat grass-covered gravel bar near the Arkansas River at the mouth of Kamloops Creek, Colo. The gravel occurred on a false clay bedrock which sloped about 1 inch to the foot. A 6-inch sand streak occurred just above the bedrock. The ground was worked in cuts 8 feet wide and 150 feet long. There was enough dump room at the lower end of the cuts. The bank was undercut in the sandy layer by a jet of water from a fire hose, using a 2-inch nozzle and a 6-foot head; the overlying gravel broke down and was washed into the boxes by the ground-sluice water. About 60 miner’s inches was used. Lumps were broken by picking, and all boulders were thrown back beside the sluice boxes. A tight wing dam built of sod directed the water into the head of the boxes. A 5- by 20-foot steel sheet was placed in the cut 18 inches below the level and ahead of the sluice; the edges of the sheet were turned slightly upward, and the space underneath was packed at the edges with sod. The sheet was moved up to the face of the cut as soon as room was made; the sluice was extended to the lower end of the sheet at the same time. Bedrock was cleaned up by shoveling the top of the false clay bedrock onto the sheet where clay that did not break up was puddled with a hoe or shovel. The material on the sheet was then shoveled into the boxes. Most of the gold was caught on the sheet.

The boxes were 18 inches wide and had a grade of ¼ inch to the foot. The riffles consisted of 1- by 1-inch transverse wooden cleats placed over burlap. Quicksilver was used in the boxes when cleaning up.

About 16 cubic yards per man per day was washed when ground sluicing. Including clean¬up time, the average was about 12 cubic yards per day. At $3.50 per day the labor cost would have been 28 cents. The total operating cost, including 3 cents for supplies, would have been 31 cents per cubic yard.

Kamloops

The Kamloops Placer Gold Mining Co. was running a cut on a bench to reach some reputed rich ground near Granite, Colo., in July 1932. The cut started at the edge of old hydraulic workings. Bedrock had not been reached. Part of the gravel was tight and contained some boulders 4 or 5 tons in weight. On July 17, 1932 a cut 15 feet wide and 525 feet long had been run. The average depth was about 14 feet and the maximum 18 feet. The sluice was 30 inches wide, 20 inches high, and 504 feet long. Dredge-type Hungarian riffles were used. Boxes were set at the flat grade of 3 inches to the 12-foot box to reach bedrock as soon as possible. To prevent clogging, as much of the washed oversize as could be loaded conveniently was removed from the pit ahead of the boxes with a power dragline. This machine had a 35-foot boom and a 40-foot line. Boulders up to 3 tons in weight could be lifted out of the cut with the dragline by using chains. Boulders over 3 tons in weight were blockholed and blasted. The dragline bucket or dipper was made with a grizzly bottom with 2-inch spacing between the bars. About 20 percent of the material was removed by the dragline.

Water under a 15-foot head was directed against the bank by a 2-inch nozzle mounted on a stand with a “gooseneck.” The ground-sluice water flowed down the face. About 100 miner’s inches was used.

The crew consisted of two men. One operated the dragline and nozzle, the other attended the sluice and picked down the bank. The dragline operator on day shift acted as superintendent. Two shifts were worked, and an average of 73 cubic yards was handled per day. Allowing a wage of $3.50 per day for all four men the labor cost would be 20 cents per cubic yard. With supplies at 4 cents per cubic yard the total operating cost would be 24 cents, disregarding supervision, rental, and repairs to the dragline

Willow Creek

Four men – Laury, Kennedy, Lund, and Neal – were running a cut to reach bedrock on Willow Creek near Therma, N. Mex. On July 20, 1932 the cut was 130 feet long and averaged 24 feet wide and 10 feet deep. A dam had been built above the mine across the creek on bedrock, which raised the underground flow of water above the surface. When ready to boom the gate in the dam was opened by hand. The water poured out of a 10-inch pipe under a 3-foot head and was conducted in a 12-inch pipe to the head of the cut. The pipe extended over the face of the cut, and the stream of water-struck the toe of the slope. The pit was boomed four times per day; the length of each booming period was 27 minutes. The rest of the time, while the reservoir was refilling, was spent in throwing out boulders and installing boxes. While booming, two men worked in the face with shovels, assisting the action of the water. The third man watched the boxes to see that they did not become clogged, and the fourth man stayed at the end of the sluice box and pulled away the tailings when they tended to pile up.

The pit had not reached bedrock when this occurred the face would be widened to include all of the gravel channel. The sluice was 18 inches wide, 10 inches high, 600 feet long, and set on a grade of 6 inches to the 12-foot box. The riffles consisted of round blocks 5 inches long and 18 inches in diameter that just fit in the boxes, A 1- by 4-inch strip nailed on the inside of the box held the blocks in place. In addition to acting as gold catchers the blocks protected the bottom of the boxes.

Lumber cost $22 per M at a sawmill near by. An average of 4 cubic yards per man-shift was being washed; not enough water was available for the economical utilization of the labor. At $3.50 per shift the labor cost would have been 87 cents per cubic yard. With supplies at 4 cents, the total operating cost would have been 91 cents. A large part of the work consisted of building 470 feet of sluiceway down the canyon, below where the cut was started, to provide dump room. Deducting the cost of this, the labor cost, would have been about. 40 instead of 87 cents.

Camp Bird

Joe Witherspoon, with one man, was ground-sluicing on California Gulch near Laurin, Sheridan County, Mont., during the 1932 season. The gravel occurred along the bottom of the gulch on the present stream course and averaged about 7 feet deep and 20 feet wide. The pit, an extension of old workings, was 450 feet long on July 5, 1932. (See fig. 9 C.) Overlying the gravel was 2½ feet of loam. The top soil was piped off with a 1-inch nozzle on a firehose connected to a 6-inch pipe with a 60-foot head. The hose also was used for cutting the bank. The pit was boomed on an average of twice a day, the flush water running about 30 minutes each time. The remaining time was used in removing boulders and cutting the bank. Enough water was available in the early part of the season to boom 4 or 5 times per day. The ground-sluice water was deflected and held against the bank by boards and dry walls. A part of the natural flow of the stream ran through the pit while the boulders were being thrown out. Boulders over 6 inches in diameter that could be lifted by hand were rolled or lifted back on the washed bedrock. Stones 3 to 6 inches in diameter were thrown by hand clear of the pit. Boulders too large to lift were blown out of the pit with 40-percent-strength gelatin dynamite. Several sticks of explosive were placed under the boulders so that on detonation the boulders were lifted clear of the pit. The boulders were blasted when partly submerged in water, which acted as stemming for the explosive. Three 12-foot boxes, 22 inches wide and 16 inches high, set on a grade of 1 inch to the foot were used little gold, however, got into the sluice.

It was estimated that about 50 shifts would be required to clean up the bedrock that was exposed on July 5. In doing this the boulders would have to be moved a second time. The bedrock was soft and would be picked and shoveled into clean-up boxes.

Between 50 and 60 cubic yards was being washed per day. Allowing clean-up time, the average for the period was about 36 cubic yards per day or 18 per man-shift. At $3.50 per day the labor cost would have been 20 cents, and with 2 cents per cubic yard for supplies the total operating cost would have been 22 cents.

Bennet

I. B. Bennet had been ground-sluicing by booming on a side gulch of Quartz Creek near Rivulet, Mont., for a number of years. The bedrock sloped about 1½ inches to the foot. The gravel was 12 to 25 feet deep and averaged about 3 5 feet. As the reservoir filled it discharged through a 24- by 24-inch opening, the gate of which operated automatically. Figure 7 A, shows the details of the automatic gate. At the beginning of the season the reservoir filled every 2 hours and for a period of 9 days, when the snow was melting most rapidly, every 20 minutes. At the end of the season the reservoir filled only once a day. The flush water was directed against the bank, which was kept in the form of a semicircle. As the bank was washed away, the coarser gravel, about 3 feet in depth, was left on bedrock. At the end of the season this 3 feet of material was loosened by picking, and the boulders were rolled back onto bedrock; the water carried away the rest of the material. An area 20 feet wide and 100 feet long was washed during the 1932 season of 50 days. About 1 foot of boulders was left to be moved again as the bedrock was cleaned. It was estimated that about 3 weeks would be required for this work. The bedrock was hard and medium rough. It would be cleaned by hand crevices must be dug out and scraped. An average of 23 yards was mined per 8 hours during the washing period. Although only one 8-hour shift per day was spent on the ground, the booming went on for 24 hours.

At $3.50 per day the labor cost would be 21 cents per cubic yard. The total operating cost was about 22 cents.

Harvey

C. W. Robertson had been working the Harvey placer near Lincoln, Mont., for the past 15 years. The gravel worked was in the bottom of a gulch along the stream bed. The depth ranged from 18 to 24 feet and averaged 22 feet; the width was 90 feet (fig. 9, D). The gravel contained an unusually large proportion of boulders, some of which weighed as much as 8 tons. The pit advanced the full width of the channel. The washing was done by booming. When work began in the spring the reservoir would fill in 9 minutes, and the full stream would run for 15 minutes. In July a boom occurred once an hour and ran only 2½ minutes. The gate opened automatically (see fig. 7, B). The water was taken from the reservoir in a flume 5 feet wide, 3 feet deep, and 400 feet long. At the head of the pit the flume divided into five branches, the ends of which extended over the face of the pit. During booming the water dropped into the pit through two adjoining branches. The bottom 6 feet of the gravel was fairly tight and partly bound with clay. The overcast allowed the water to drop on this stratum; as the lower gravel was cut away the bank above sloughed down. The sluice was 38 inches wide, 36 inches deep, and 192 feet long and had a grade of ¾ inch to the foot. Individual boxes were 12 feet long. Pole riffles 12 feet long were used in the boxes. The sluice was cleaned up at the end of the season. It was brought upward in the pit to one side of the center (see fig. 9, D). Twelve-foot cuts were taken from the face of the pit on alternate sides of the sluice. A new box was put in after every pair of cuts.

Boulders were handled by means of two well-built hand-operated derricks and piled back of the ground being worked; they filled the pit to a depth of 10 feet. A dry wall was built up of boulders on either side of the sluice. One derrick stood on a platform across the head of the sluice boxes on the rock walls. The other derrick was on a platform on the main rock pile. The derricks were built of 10 to 12 inch round timber. The boom of the one over the sluice box was 30 feet long and that of the other 35 feet long. The masts were 20 feet long. The winch cables were 5/8 inch in diameter. The derricks were set so that a load from one could be taken up and dumped by the other. A sling platform was used for handling any boulders that a man could roll onto it. A chain was used for larger ones. No blasting was necessary.

Each 12-foot section of bedrock was cleaned up as the cut was completed. The bedrock, which was fairly soft was loosened by picking and then hosed into the sluice by a 3½-inch firehose connected to an 18-inch pipe from one of the boxes on the bank. The 22-foot head did not give enough pressure to cut the bedrock. After a section was cleaned a team was brought into the pit, and as many large boulders as could be handled from near the face were dragged onto the cleaned-up bedrock. A dry wall was then built to deflect the water to the head of the sluice for mining the next cut. Old rags were used in the wall near the head of the box, and sod was used elsewhere to make the wall water tight for a height of 12 or 18 inches. The wall was raised and the space back of it filled with boulders as the next cut was taken out above.

To July 7, 1932 when the water had materially decreased, 2,520 cubic yards had been washed in 50 working days. A total of 3,800 cubic yards was washed by the end of the season (in the middle of September). Robertson worked the mine alone. Up to July 7, 50 cubic yards had been washed per day. Although only one shift per day was worked the booming went on 24 hours. The labor cost would have been 7 cents; allowing 3 cents for supplies the total cost was 10 cents per cubic yard. For the whole season an average of 32 cubic yards was washed per shift. This would amount to 11 cents per cubic yard for labor, or a total of 14 cents. Some work, such as repairing the dam and flume, was done during the winter; this would increase the total cost per cubic yard 2 or 3 cents.

Magnus and Ole Lindquist. Inc.

This company was running a long cut by ground-sluicing to reach bedrock near Liberty, Wash. After bedrock was reached it was planned to put in hydraulic equipment. On June 23 the cut was about 400 feet long and averaged 20 by 20 feet in cross-section. The sluice boxes were 48 inches wide and 36 inches high. The grade was 5 percent. Riffles were 20-pound steel rails set lengthwise 2 inches above the bottom of the box and 2 inches apart. All boulders up to 15 inches in diameter were put through the boxes, Any over this size were first broken by blasting, then run down the sluice.

Water for booming was stored in a reservoir; the gate was 6 by 6 feet and was opened automatically. The boom lasted 15 minutes, and an average of six booms occurred during the shift; the booming continued 24 hours each day. The water poured over the face of the cut; it broke down the face and scoured out the cut without much assistance from the miners. Boulders occasionally were started rolling and assisted through the boxes by hand.

Of the 9 men employed 3 worked at the sawmill cutting lumber for the sluice boxes; 3 were putting new boxes in the cut as room was made and at the lower end as the tailings filled up the limited dump room; 2 worked at the end of the sluice, leveling off the tailings; and 1 man watched the boxes and supervised the work. The three men who worked on boxes also handled boulders and watched the water during the booming period. The low yardage (7 cubic yards) per man-shift was due mainly to the unusually large number of men employed in cutting lumber and putting in boxes. The total labor cost at $3.50 per shift would have been 50 cents. With 4 cents for supplies the total cost would have been 54 cents per cubic yard. Exclusive of the extra men required to level off the tailing and to extend the boxes at the lower end of the sluice on account of limited dump room, the labor cost would have been about half that indicated.

At the Morgan placer the gravel was loosened with difficulty by picking, hence the high cost per cubic yard. The low efficiency of labor at the Bar No. 1 mine was mainly the result of inexperience. The costs at the other mines listed represent average conditions.